Composite bow

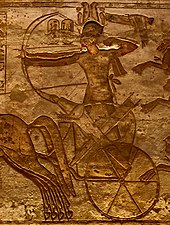

Archaeological finds and art indicate composite bows have existed since the second millennium BCE, but their history is not well recorded, being developed by cultures without a written tradition.

Some composite bows have nonbending tips ("siyahs"), which need to be stiff and light; they may be made of woods such as Sitka spruce.

Traditionally, ox tendons are considered inferior to wild-game sinews since they have a higher fat content, leading to spoilage.

[1] Sinew has greater elastic tension properties than wood, again increasing the amount of energy that can be stored in the bow stave.

Strings and arrows are essential parts of the weapon system, but no type of either is specifically associated with composite bows throughout their history.

[2] For most practical non-mounted archery purposes, composite construction offers no advantage; "the initial velocity is about the same for all types of bow... within certain limits, the design parameters... appear to be less important than is often claimed."

Ancient Mediterranean civilizations, influenced by Eastern Archery, preferred composite recurve bows, and the Romans manufactured and used them as far north as Britannia.

Waterproofing and proper storage of composite bows were essential due to India's extremely wet and humid subtropical climate and plentiful rainfall today (which averages 970–1,470 mm or 38–58 inches in most of the country, and exceeds well over 2,500 mm or 100 inches per year in the wettest areas due to monsoons).

[8] However, archaeological investigation of the Asiatic steppe is still limited and patchy; literary records of any kind are late and scanty and seldom mention details of bows.

[1] There are arrowheads from the earliest chariot burials at Krivoye Lake, part of the Sintashta culture about 2100–1700 BCE, but the bow that shot them has not survived.

[15] By the 4th century BCE, chariotry had ceased to have military importance, replaced by cavalry everywhere (except in Britannia, where charioteers are not recorded as using bows).

Classic tactics for horse-mounted archers included skirmishing: they would approach, shoot, and retreat before any effective response could be made.

[16] The term Parthian shot refers to the widespread horse-archer tactic of shooting backwards over the rear of their horses as they retreated.

However, horse archers did not make an army invincible; Han General Ban Chao led successful military expeditions in the late 1st century CE that conquered as far as Central Asia, and both Philip of Macedon and his son Alexander the Great defeated horse archer armies.

The military of the Han dynasty (220 BCE–206 CE) utilized composite crossbows, often in infantry square formations, in their many engagements against the Xiongnu.

Until 1571, archers with composite bows were a main component of the forces of the Ottoman Empire, but in the Battle of Lepanto in that year, they lost most of these troops and never replaced them.

Rather, each design type represents one solution to the problem of creating a mobile weapon system capable of hurling lightweight projectiles.

[23] They were the normal weapon of later Roman archers, both infantry and cavalry units (although Vegetius recommends training recruits "arcubus ligneis", with wooden bows).

"Alanic graves in the Volga region dating to the 3rd to 4th century CE signal the adoption of the Qum-Darya type by Sarmatian peoples from Hunnic groups advancing from the East.

Germanic tribes transmitted their respect orally for a millennium: in the Scandinavian Hervarar saga, the Geatish king Gizur taunts the Huns and says, "Eigi gera Húnar oss felmtraða né hornbogar yðrir."

The Romans, as described in the Strategikon, Procopius's histories, and other works, changed the entire emphasis of their army from heavy infantry to cavalry, many of them armed with bows.

The grip laths stayed essentially the same except that a fourth piece was sometimes glued to the back of the handle, enclosing it with bone on all four faces.

Turkish armies included archers until about 1591 (they played a major role in the Battle of Lepanto (1571),[17] and flight archery remained a popular sport in Istanbul until the early 19th century.

[30][33] Fragments of bone laths from composite bows were found among grave goods in the United Arab Emirates dating from the period between 100 BCE and 150 CE.

[42] However, in the beginning of the 21st century, there has been a revival in interest among craftsmen looking to construct bows and arrows in the traditional Chinese style.

[43] The Mongolian tradition of archery is attested by an inscription on a stone stele that was found near Nerchinsk in Siberia: "While Genghis Khan was holding an assembly of Mongolian dignitaries, after his conquest of Sartaul (Khwarezm), Yesüngge (the son of Genghis Khan's younger brother) shot a target at 335 alds (536 m)".

[46] Modern Hungarians have attempted to reconstruct the composite bows of their ancestors and have revived mounted archery as a competitive sport.

After the introduction of domesticated horses, newly mounted groups rapidly developed shorter bows, which were often given sinew backing.

Other less satisfactory materials than horn have been used for the belly of the bow (the part facing the archer when shooting), including bone, antler, or compression-resistant woods such as osage orange, hornbeam, or yew.

Materials that are strong under tension, such as silk, or tough wood, like hickory, have been used on the back of the bow (the part facing away from the archer when shooting).