Hydrogen economy

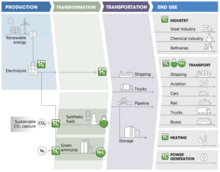

[4] Virtually all of the 100 million tonnes[5] of hydrogen produced each year is used in oil refining (43% in 2021) and industry (57%), principally in the manufacture of ammonia for fertilizers, and methanol.

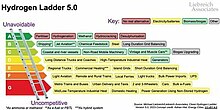

[7] The future end-uses are likely in heavy industry (e.g. high-temperature processes alongside electricity, feedstock for production of green ammonia and organic chemicals, as alternative to coal-derived coke for steelmaking), long-haul transport (e.g. shipping, and to a lesser extent hydrogen-powered aircraft and heavy goods vehicles), and long-term energy storage.

[8][9] Other applications, such as light duty vehicles and heating in buildings, are no longer part of the future hydrogen economy, primarily for economic and environmental reasons.

[12] The cost of low- and zero-carbon hydrogen is likely to influence the degree to which it will be used in chemical feedstocks, long haul aviation and shipping, and long-term energy storage.

[15] The term "hydrogen economy" itself was coined by John Bockris during a talk he gave in 1970 at General Motors (GM) Technical Center.

[16] Bockris viewed it as an economy in which hydrogen, underpinned by nuclear and solar power, would help address growing concern about fossil fuel depletion and environmental pollution, by serving as energy carrier for end-uses in which electrification was not suitable.

Modern interest in the hydrogen economy can generally be traced to a 1970 technical report by Lawrence W. Jones of the University of Michigan,[18] in which he echoed Bockris' dual rationale of addressing energy security and environmental challenges.

[19] A spike in attention for the hydrogen economy concept during the 2000s was repeatedly described as hype by some critics and proponents of alternative technologies,[21][22][23] and investors lost money in the bubble.

[8] They focus on the need to limit global warming to 1.5 °C and prioritize the production, transportation and use of green hydrogen for heavy industry (e.g. high-temperature processes alongside electricity,[31] feedstock for production of green ammonia and organic chemicals,[8] as alternative to coal-derived coke for steelmaking),[32] long-haul transport (e.g. shipping, aviation and to a lesser extent heavy goods vehicles), and long-term energy storage.

[4] Most hydrogen comes from dedicated production facilities, over 99% of which is from fossil fuels, mainly via steam reforming of natural gas (70%) and coal gasification (30%, almost all of which in China).

[6]: 18, 22 In oil refining, hydrogen is used, in a process known as hydrocracking, to convert heavy petroleum sources into lighter fractions suitable for use as fuels.

In this process, hydrogen is produced from a chemical reaction between steam and methane, the main component of natural gas.

[46][47] Green methanol is a liquid fuel that is produced from combining carbon dioxide and hydrogen (CO2 + 3 H2 → CH3OH + H2O) under pressure and heat with catalysts.

[50] Ethanol plants in the midwest are a good place for pure carbon capture to combine with hydrogen to make green methanol, with abundant wind and nuclear energy in Iowa, Minnesota, and Illinois.

[59] For example, in steelmaking, hydrogen could function as a clean energy carrier and also as a low-carbon catalyst replacing coal-derived coke.

[32] The imperative to use low-carbon hydrogen to reduce greenhouse gas emissions has the potential to reshape the geography of industrial activities, as locations with appropriate hydrogen production potential in different regions will interact in new ways with logistics infrastructure, raw material availability, human and technological capital.

[30] With the rapid rise of electric vehicles and associated battery technology and infrastructure, hydrogen's role in cars is minuscule.

[69][70] An alternative to gaseous hydrogen as an energy carrier is to bond it with nitrogen from the air to produce ammonia, which can be easily liquefied, transported, and used (directly or indirectly) as a clean and renewable fuel.

[76] Hydrogen poses a number of hazards to human safety, from potential detonations and fires when mixed with air to being an asphyxiant in its pure, oxygen-free form.

These include mechanical approaches such as using high pressures and low temperatures, or employing chemical compounds that release H2 upon demand.

Xcel Energy is going to build two combined cycle power plants in the Midwest that can mix 30% hydrogen with the natural gas.

Blue hydrogen production costs are not anticipated to fall substantially by 2050,[95][92]: 28 can be expected to fluctuate with natural gas prices and could face carbon taxes for uncaptured emissions.

[101] The distribution of hydrogen for the purpose of transportation is being tested around the world, particularly in the US (California, Massachusetts), Canada, Japan, the EU (Portugal, Norway, the Netherlands, Denmark, Germany), and Iceland.

The countries with the largest amount of natural gas vehicles are (in order of magnitude):[102] Iran, China, Pakistan, Argentina, India, Brazil, Italy, Colombia, Thailand, Uzbekistan, Bolivia, Armenia, Bangladesh, Egypt, Peru, Ukraine, the United States.

The buses' fuel cells used a proton exchange membrane system and were supplied with raw hydrogen from a BP refinery in Kwinana, south of Perth.

[107] Countries in the EU which have a relatively large natural gas pipeline system already in place include Belgium, Germany, France, and the Netherlands.

Corridor H2, a similar initiative, will create a network of hydrogen distribution facilities in Occitania along the route between the Mediterranean and the North Sea.

[127] Saudi Arabia as a part of the NEOM project, is looking to produce roughly 1.2 million tonnes of green ammonia a year, beginning production in 2025.

As of October 2024, 188km of underground pipelines have been laid to connect hydrogen produced as a byproduct from petrochemical complexes to the city center.

[150] Australian clean energy company Pure Hydrogen Corporation Limited announced on July 22 that it has signed an MoU with Vietnam public transportation.