Hyperinflation

[1] Effective capital controls and currency substitution ("dollarization") are the orthodox solutions to ending short-term hyperinflation; however there are significant social and economic costs to these policies.

Many governments choose to attempt to solve structural issues without resorting to those solutions, with the goal of bringing inflation down slowly while minimizing social costs of further economic shocks.

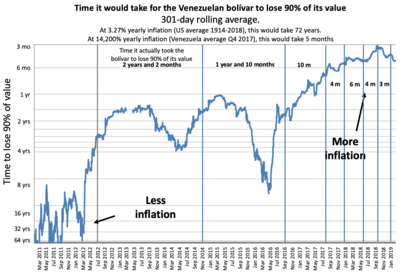

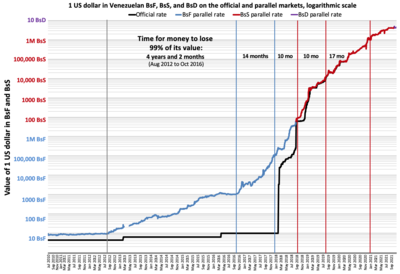

[3] Typically, however, the general price level rises even more rapidly than the money supply as people try ridding themselves of the devaluing currency as quickly as possible.

A sharp decrease in real tax revenue coupled with a strong need to maintain government spending, together with an inability or unwillingness to borrow, can lead a country into hyperinflation.

Monetarist theories hold that hyperinflation occurs when there is a continuing (and often accelerating) rapid increase in the amount of money that is not supported by a corresponding growth in the output of goods and services.

Inflation can obscure quantitative assessments of the true cost of living, as published price indices only look at data in retrospect, so may increase only months later.

One example of this is during periods of warfare, civil war, or intense internal conflict of other kinds: governments need to do whatever is necessary to continue fighting, since the alternative is defeat.

[17] Hyperinflation increases stock market prices, wipes out the purchasing power of private and public savings, distorts the economy in favor of the hoarding of real assets, causes the monetary base (whether specie or hard currency) to flee the country, and makes the afflicted area anathema to investment.

Hyperinflation is ended by drastic remedies, such as imposing the shock therapy of slashing government expenditures or altering the currency basis.

Products available to consumers may diminish or disappear as businesses no longer find it economic to continue producing and/or distributing such goods at the legal prices, further exacerbating the shortages.

[25] Since the late 2010s, prolonged inflation remained a constant problem of economy of Argentina, with an annual rate of 25% in 2017, second only to Venezuela in South America and the highest in the G20.

[26][29] Despite the high-interest rates and IMF support, investors feared that the country might fall into a sovereign default once again, especially if another administration were to be voted in during the next election cycle, and started pulling out investments.

The new peronist administration immediately refused to take the remaining $11 billion of the loan, arguing that it was no longer obliged to adhere to the IMF conditions.

[36] These measures caused the underground foreign exchange market to come back to life, despite efforts made by the previous Macri's administration to stamp it out, further weakening Argentina's control over its economy.

In 1922, inflation in Austria reached 1,426%, and from 1914 to January 1923, the consumer price index rose by a factor of 11,836, with the highest banknote in denominations of 500,000 Kronen.

[49] During the period of inflation Brazil adopted a total of six different currencies, as the government constantly changed due to rapid devaluation and increase in the number of zeros.

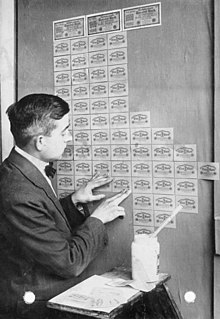

According to Dillaye: "Seventeen manufacturing establishments were in full operation in London, with a force of four hundred men devoted to the production of false and forged Assignats.

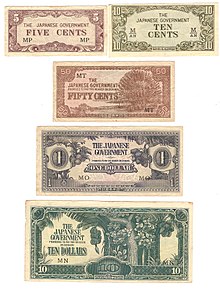

As the occupation proceeded, the Japanese authorities printed more money to fund their wartime activities, which resulted in hyperinflation and a severe depreciation in value of the banana note.

Having nominated an all-new government and being granted extraordinary lawmaking powers by the Sejm for a period of six months, he introduced a new currency, the złoty ("golden" in Polish), established a new national bank and scrapped the inflation tax, which took place throughout 1924.

Survivors of the war often tell tales of bringing suitcases or bayong (native bags made of woven coconut or buri leaf strips) overflowing with Japanese-issued notes.

A seven-year period of uncontrollable spiralling inflation occurred in the early Soviet Union, running from the earliest days of the Bolshevik Revolution in November 1917 to the reestablishment of the gold standard with the introduction of the chervonets as part of the New Economic Policy.

[88] This forecast was criticized by Steve H. Hanke, professor of applied economics at The Johns Hopkins University and senior fellow at the Cato Institute.

One of these sources claims that the disclosure of economic numbers may bring Venezuela into compliance with the IMF, making it harder to support Juan Guaidó during the presidential crisis.

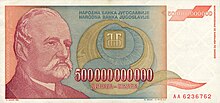

The Belgrade government of Slobodan Milošević backed ethnic Serbian forces in the conflict, resulting in a United Nations boycott of Yugoslavia.

The UN boycott collapsed an economy already weakened by regional war, with the projected monthly inflation rate accelerating to one million percent by December 1993 (prices double every 2.3 days).

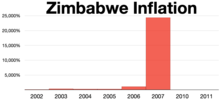

Inflation was relatively steady until the early 1990s when economic disruption caused by failed land reform agreements and rampant government corruption resulted in reductions in food production and the decline of foreign investment.

Several multinational companies began hoarding retail goods in warehouses in Zimbabwe and just south of the border, preventing commodities from becoming available on the market.

[100][101][102][103] The result was that to pay its expenditures Mugabe's government and Gideon Gono's Reserve Bank printed more and more notes with higher face values.

The Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe revalued on 1 August 2006 at a ratio of 1,000 ZWD to each second dollar (ZWN), but year-to-year inflation rose by June 2007 to 11,000% (versus an earlier estimate of 9,000%).

Ironically, following the abandonment of the ZWR and subsequent use of reserve currencies, banknotes from the hyperinflation period of the old Zimbabwe dollar began attracting international attention as collectors items, having accrued numismatic value, selling for prices many orders of magnitude higher than their old purchasing power.