Hyperinflation in Zimbabwe

[2] In mid-2015, Zimbabwe announced plans to have completely switched to the United States dollar by the end of that year.

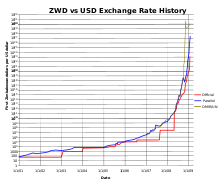

However, that did not reflect reality because, in terms of purchasing power on the open and black markets, it was less valuable, due primarily to the higher inflation in Zimbabwe.

Wheat production for non-drought years was proportionally higher than previously, and the tobacco industry was thriving.

From 1991 to 1996, the Zimbabwean ZANU–PF President Robert Mugabe embarked on an Economic Structural Adjustment Programme (ESAP) that had serious negative effects on Zimbabwe's economy.

In the late 1990s, the government instituted land reforms in the name of anti-colonialism intended to evict white landowners and place their holdings in the hands of black farmers.

The Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe blamed the hyperinflation on economic sanctions imposed by the United States of America, the IMF, and the European Union.

[15][16] These sanctions affected the government of Zimbabwe,[17] asset freezes and visa denials targeted at 200 specific Zimbabweans closely tied to the Mugabe regime.

[18] There were also restrictions placed on trade with Zimbabwe, by both individual businesses and the US Treasury Department's Office of Foreign Assets Control.

[24] Land reform lowered agricultural output, especially in tobacco, which accounted for one-third of Zimbabwe's foreign-exchange earnings.

An objective reason was, again, that farms were put in the hands of inexperienced people; and subjectively, that the move undermined the security of property.

[25] Zimbabwean troops, trained by North Korean soldiers, conducted a massacre in the 1980s in the southern provinces of Matabeleland and Midlands, though Mugabe's government cites guerrilla attacks on civilian and state targets.

One aspect of this reform sought to discriminate against white people specifically and many were forced by the regime to sign over their businesses to the black majority.

[27] The Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe responded to the dwindling value of the dollar by repeatedly arranging the printing of further banknotes,[28][29][30][31][32] often at great expense from overseas suppliers.

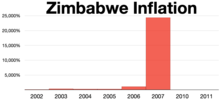

[33][34] By late 2008, inflation had risen so high that ATMs for one major bank gave a "data overflow error" and stopped customers' attempt to withdraw money with so many zeros.

The Old Mutual Implied rate was a widely adopted benchmark rate for unofficial currency exchange until intervention by the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe in May 2008 prohibited the transfer out of the country of shares in Old Mutual, ABC and Kingdom Meikles Africa, thereby blocking their fungibility.

Any Zimbabwean dollars acquired needed to be exchanged for foreign currency on the parallel market immediately,[58] or the holder would suffer a significant loss of value.

A driver might have to exchange money three times a day, not in banks but in back office rooms and in parking lots.

The black market served the demand for daily goods such as soap and bread, as grocery stores operating within the law no longer sold items whose prices were strictly controlled, or charged customers more if they were paying in Zimbabwean dollars.

[60] In May 2022, it was reported that the devaluation of the Zimbabwe dollar's black market exchange rate, which is used in most financial transactions in the economy, has been driving up inflation in the country.

As larger bills were needed to pay for menial amounts, the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe planned to print and circulate denominations of up to Z$10, 20, 50, and 100 trillion.

[63] In 2006, before hyperinflation reached its peak, the bank announced it would print larger bills to buy foreign currencies.

The Reserve Bank printed Z$21 trillion dollars to pay off debts owed to the International Monetary Fund.

[65] In July 2008, the governor of the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe, Gideon Gono, announced a new Zimbabwean dollar, this time with 10 zeros removed.

[68] This implicitly solved the chronic problem of lack of confidence in the Zimbabwean dollar, and compelled people to use the foreign currency of their choice.

This move was designed to stop speculation against the Zimbabwean dollar and was part of a raft of measures to arrest its rapid devaluation on the black market.

[61] In June 2015, the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe said it would begin a process to "demonetize" (i.e., to officially value a fiat currency at zero).

[3] In December 2015, Patrick Chinamasa, the Zimbabwe Minister of Finance, said they would make the Chinese yuan their main reserve currency and legal tender after China cancelled US$40 million in debts.

The annual inflation rate had risen to 676% in March 2020, and there was a bleak economic outlook due to the effects of a drought in 2019 and the COVID-19 pandemic.

[84] The same month, Finance minister Mthuli Ncube said the GVT would not hesitate to intervene to cushion against price increases and exchange rate volatility.