Hyperinflation in the Weimar Republic

This national debt was substantially increased by 50 billion marks of reparations payable in cash and in-kind (e.g., with coal and timber) under the May 1921 London Schedule of Payments agreed after the Versailles treaty.

This was to be done by annexing resource-rich industrial territory in the west and east and imposing cash payments to Germany, similar to the French indemnity that followed German victory over France in 1870.

[1] John Maynard Keynes characterised the inflationary policies of various wartime governments in his 1919 book The Economic Consequences of the Peace as follows: The inflationism of the currency systems of Europe has proceeded to extraordinary lengths.

The various belligerent Governments, unable, or too timid or too short-sighted to secure from loans or taxes the resources they required, have printed notes for the balance.The value of the German currency continued to fall in the immediate aftermath of the war.

By late 1919, the German government had signed the Treaty of Versailles, which included an agreement to pay substantial reparations to the Allied powers both in hard cash and in in-kind shipments of goods such as coal and timber.

Of this, 50 billion gold marks was listed in A and B bonds payable under the quarterly deadlines in the schedule; the remaining sum, about 82 billion gold marks, was listed as C bonds that were somewhat hypothetical and not payable under the schedule but instead left to an undefined future date, with the Germans being informed that they realistically would not have to pay them.

[10] At this point, customs posts in the west of Germany were occupied by Allied officials, so that the schedule of payments could be enforced.

[11] German officials claimed this was in order to make cash payments owed to the Allies using foreign currency.

British and French experts stated that this was in an effort to ruin the German currency and, as well as escaping the need for budgetary reform, avoid paying reparations altogether, a claim supported by Reich Chancellery records showing that delaying the currency and budgetary reform that could have addressed hyperinflation was seen as advantageous.

Whilst ruinous to the economy and politically destabilising, hyperinflation had advantageous aspects for the German government as, although the war reparations were not listed in paper currency, domestic debts owed from the war were listed, meaning that inflation greatly reduced this debt relative to revenues.

[5]: 245 The German government's response was to order a policy of passive resistance in the Ruhr, with workers being told to do nothing which helped the French and Belgians in any way.

The government paid these workers by printing more and more banknotes, with Germany soon being swamped with paper money, exacerbating the hyperinflation even further.

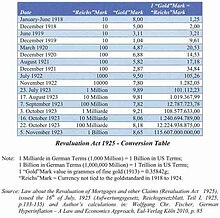

[17] The hyperinflation crisis led prominent economists and politicians to seek a means to stabilize German currency.

[21] After 12 November 1923, when Hjalmar Schacht became currency commissioner, Germany's central bank (the Reichsbank) was not allowed to discount any further government Treasury bills, which meant the corresponding issue of paper marks also ceased.

The German government had the choice of a revaluation law to finish the hyperinflation quickly or of allowing sprawling and the political and violent disturbances on the streets.

[11][5]: 238 British and French experts claimed that the German leadership were purposefully stoking inflation as a way of avoiding paying reparations, as well as a way of avoiding budgetary reforms – a view later supported by analysis of Reich Chancellery record showing that tax reform and currency stabilisation was delayed in 1922–23 in the hope of reductions in reparations.

The resulting deficit was financed by some combination of issuing bonds and simply creating more money: both increasing the supply of German mark-denominated financial assets on the market and so further reducing the currency's price.

If they stopped inflation, there would be immediate bankruptcies, unemployment, strikes, hunger, violence, collapse of civil order, insurrection and possibly even revolution.

The hyperinflation drew significant interest, as many of the dramatic and unusual economic behaviors now associated with hyperinflation were first documented systematically: exponential increases in prices and interest rates, redenomination of the currency, consumer flight from cash to hard assets and the rapid expansion of industries that produced those assets.

[39] According to one study, many Germans conflate hyperinflation in the Weimar Republic with the Great Depression, seeing the two separate events as one big economic crisis that encompassed both rapidly rising prices and mass unemployment.

[41] Firms responded to the crisis by focusing on those elements of their information systems they identified as essential to continuing operations.

With the continuous acceleration of inflation, human resources were redeployed to the most critical corporate functions, in particular those involved in the remuneration of labor.