Hippocratic Oath

In its original form, it requires a new physician to swear, by a number of healing gods, to uphold specific ethical standards.

As the foundational articulation of certain principles that continue to guide and inform medical practice, the ancient text is of more than historic and symbolic value.

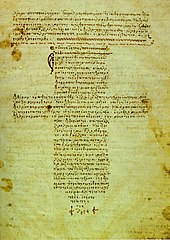

[5] I swear by Apollo Healer, by Asclepius, by Hygieia, by Panacea, and by all the gods and goddesses, making them my witnesses, that I will carry out, according to my ability and judgment, this oath and this indenture.

To hold my teacher in this art equal to my own parents; to make him partner in my livelihood; when he is in need of money to share mine with him; to consider his family as my own brothers, and to teach them this art, if they want to learn it, without fee or indenture; to impart precept, oral instruction, and all other instruction to my own sons, the sons of my teacher, and to indentured pupils who have taken the Healer's oath, but to nobody else.

A related phrase is found in Epidemics, Book I, of the Hippocratic school: "Practice two things in your dealings with disease: either help or do not harm the patient".

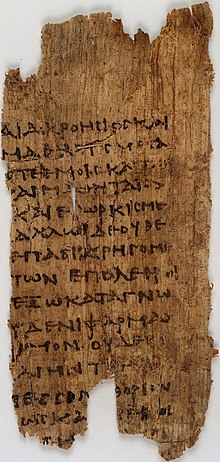

[10] The oath is arguably the best known text of the Hippocratic Corpus, although most modern scholars do not attribute it to Hippocrates himself, estimating it to have been written in the fourth or fifth century BC.

[12] While Pythagorean philosophy displays a correlation to the Oath's values, the proposal of a direct relationship has been mostly discredited in more recent studies.

[21] In the 1st or 2nd century AD work Gynaecology, Soranus of Ephesus wrote that one party of medical practitioners followed the Oath and banished all abortifacients, while the other party—to which he belonged—was willing to prescribe abortions, but only for the sake of the mother's health.

[20] Olivia De Brabandere writes that regardless of the author's original intention, the vague and polyvalent nature of the relevant line has allowed both professionals and non-professionals to interpret and use the oath in several ways.

[17] The oath stands out among comparable ancient texts on medical ethics and professionalism through its heavily religious tone, a factor which makes attributing its authorship to Hippocrates particularly difficult.

Doctors who violate these codes may be subjected to disciplinary proceedings, including the loss of their license to practice medicine.

It noted that in those years the custom of medical schools to administer an oath to its doctors upon graduation or receiving a license to practice medicine had fallen into disuse or become a mere formality".

[30][failed verification] In the 1960s, the Hippocratic Oath was changed to require "utmost respect for human life from its beginning", making it a more secular obligation, not to be taken in the presence of any gods, but before only other people.

When the oath was rewritten in 1964 by Louis Lasagna, Academic Dean of the School of Medicine at Tufts University, the prayer was omitted, and that version has been widely accepted and is still in use today by many US medical schools:[31] I swear to fulfill, to the best of my ability and judgment, this covenant: I will respect the hard-won scientific gains of those physicians in whose steps I walk, and gladly share such knowledge as is mine with those who are to follow.

I will apply, for the benefit of the sick, all measures [that] are required, avoiding those twin traps of overtreatment and therapeutic nihilism.

I will remember that there is art to medicine as well as science, and that warmth, sympathy, and understanding may outweigh the surgeon's knife or the chemist's drug.

I will remember that I do not treat a fever chart, a cancerous growth, but a sick human being, whose illness may affect the person's family and economic stability.

I will remember that I remain a member of society, with special obligations to all my fellow human beings, those sound of mind and body as well as the infirm.

[36][37] In 1995, Sir Joseph Rotblat, in his acceptance speech for the Nobel Peace Prize, suggested a Hippocratic Oath for Scientists.

[39] In 2007, US citizen Rafiq Abdus Sabir was convicted for making a pledge to al-Qaeda, thus agreeing to provide medical aid to wounded terrorists.

A review of 18 of these oaths was criticized for their wide variability: "Consistency would help society see that physicians are members of a profession that's committed to a shared set of essential ethical values.

[42] Medical professionals may also be subject to other parts of the criminal and civil law for conduct contrary to both an oath taken and to a more general prohibition on, for example, doing physical or other harm to other persons.