I. M. Pei

[2][36] In the spring of 1948, Pei was recruited by New York real estate magnate William Zeckendorf to join a staff of architects for his firm of Webb and Knapp to design buildings around the country.

[40] Pei's designs echoed the work of Mies van der Rohe in the beginning of his career as also shown in his own weekend-house in Katonah, New York in 1952.

As with previous projects, abundant green spaces were central to Pei's vision, which added traditional townhouses to aid the transition from classical to modern design.

According to The Canadian Encyclopedia : its grand plaza and lower office buildings, designed by internationally famous US architect I. M. Pei, helped to set new standards for architecture in Canada in the 1960s ...

The tower's smooth aluminum and glass surface and crisp unadorned geometric form demonstrate Pei's adherence to the mainstream of 20th-century modern design.

President Kennedy had begun considering the structure of his library soon after taking office, and he wanted to include archives from his administration, a museum of personal items, and a political science institute.

[68] Pei's first proposed design included a large glass pyramid that would fill the interior with sunlight, meant to represent the optimism and hope that Kennedy's administration had symbolized for so many in the United States.

The plan generated mixed results and opinion, largely succeeding in re-developing office building and parking infrastructure but failing to attract its anticipated retail and residential development.

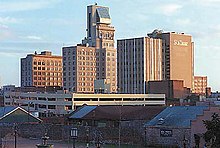

As a result, Oklahoma City's leadership avoided large-scale urban planning for downtown throughout the 1980s and early 1990s, until the passage of the Metropolitan Area Projects (MAPS) initiative in 1993.

[82] Jonsson, a co-founder of Texas Instruments, learned about Pei from his associate Cecil Howard Green, who had recruited the architect for MIT's Earth Sciences building.

John Hancock Insurance chairman Robert Slater hired I. M. Pei & Partners to design a building that could overshadow the Prudential Tower, erected by their rival.

[106] After visiting his ancestral home in Suzhou, Pei created a design based on some simple but nuanced techniques he admired in traditional residential Chinese buildings.

Younger Chinese who had hoped the building would exhibit some of Cubist flavor for which Pei had become known were disappointed, but the new hotel found more favor with government officials and architects.

Pei was also meticulous about the arrangement of items in the garden behind the hotel; he even insisted on transporting 230 short tons (210 t) of rocks from a location in southwest China to suit the natural aesthetic.

[112] As the Fragrant Hill project neared completion, Pei began work on the Javits Center in New York City, for which his associate James Freed served as lead designer.

Hoping to create a vibrant community institution in what was then a run-down neighborhood on Manhattan's west side, Freed developed a glass-coated structure with an intricate space frame of interconnected metal rods and spheres.

City regulations forbid a general contractor having final authority over the project, so architects and program manager Richard Kahan had to coordinate the wide array of builders, plumbers, electricians, and other workers.

In an attempt to soothe public ire, Pei took a suggestion from then-mayor of Paris Jacques Chirac and placed a full-sized cable model of the pyramid in the courtyard.

"[130] The pyramid achieved further widespread international recognition for its central role in the plot at the denouement of The Da Vinci Code by Dan Brown and its appearance in the final scene of the subsequent screen adaptation.

[137] Pei's design placed the rigid shoebox at an angle to the surrounding street grid, connected at the north end to a long rectangular office building, and cut through the middle with an assortment of circles and cones.

Billionaire tycoon Ross Perot made a donation of US$10 million, on the condition that it be named in honor of Morton H. Meyerson, the longtime patron of the arts in Dallas.

Given the elder Pei's history with the bank before the Communist takeover, government officials visited the 89-year-old man in New York to gain approval for his son's involvement.

The small parcel of land made a tall tower necessary, and Pei had usually shied away from such projects; in Hong Kong especially, the skyscrapers lacked any real architectural character.

Using the reflective glass that had become something of a trademark for him, Pei organized the facade around diagonal bracing in a union of structure and form that reiterates the triangle motif established in the plan.

He wrote an opinion piece for The New York Times titled "China Won't Ever Be the Same", in which he said that the killings "tore the heart out of a generation that carries the hope for the future of the country".

[148] Using a glass wall for the entrance, similar in appearance to his Louvre pyramid, Pei coated the exterior of the main building in white metal, and placed a large cylinder on a narrow perch to serve as a performance space.

The museum's coordinators were pleased with the project; its official website describes its "true splendour unveiled in the sunlight," and speaks of "the shades of colour and the interplay of shadows paying tribute to the essence of Islamic architecture".

[161] The main part of the building is a distinctive conical shape with a spiral walkway and large atrium inside, similar to that of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York City.

[162] He was known for combining traditional architectural principles with progressive designs based on simple geometric patterns—circles, squares, and triangles are common elements of his work in both plan and elevation.

In its citation, the jury said: "Ieoh Ming Pei has given this century some of its most beautiful interior spaces and exterior forms ... His versatility and skill in the use of materials approach the level of poetry.