IQ classification

[7][8] Further, a minor divergence in scores can be observed when an individual takes tests provided by different publishers at the same age.

[9] There is no standard naming or definition scheme employed universally by all test publishers for IQ score classifications.

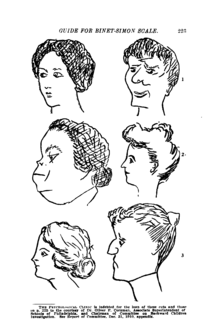

Even before IQ tests were invented, there were attempts to classify people into intelligence categories by observing their behavior in daily life.

[10][11] Those other forms of behavioral observation were historically important for validating classifications based primarily on IQ test scores.

Current IQ test publishers take into account reliability and error of estimation in the classification procedure.

[16] For example, many children in the famous longitudinal Genetic Studies of Genius begun in 1921 by Lewis Terman showed declines in IQ as they grew up.

Terman recruited school pupils based on referrals from teachers, and gave them his Stanford–Binet IQ test.

[29] For placement in school programs, for medical diagnosis, and for career advising, factors other than IQ can be part of an individual assessment as well.

The lesson here is that classification systems are necessarily arbitrary and change at the whim of test authors, government bodies, or professional organizations.

David Wechsler, using the clinical and statistical skills he gained under Charles Spearman and as a World War I psychology examiner, crafted a series of intelligence tests.

During the First World War in 1917, adult intelligence testing gained prominence as an instrument for assessing drafted soldiers in the United States.

The collective efforts of Binet, Simon, Terman, and Yerkes laid the groundwork for modern intelligence test series.

[31] The Das-Naglieri Cognitive Assessment System test was developed by Jack Naglieri and J. P. Das and published in 1997 by Riverside.

When he first chose classification for score levels, he relied partly on the usage of earlier authors who wrote, before the existence of IQ tests, on topics such as individuals unable to care for themselves in independent adult life.

Terman's first version of the Stanford–Binet was based on norming samples that included only white, American-born subjects, mostly from California, Nevada, and Oregon.

[57] Rudolph Pintner proposed a set of classification terms in his 1923 book Intelligence Testing: Methods and Results.

[4] Pintner commented that psychologists of his era, including Terman, went about "the measurement of an individual's general ability without waiting for an adequate psychological definition.

[61] Albert Julius Levine and Louis Marks proposed a broader set of categories in their 1928 book Testing Intelligence and Achievement.

[67] He devoted a whole chapter in his book The Measurement of Adult Intelligence to the topic of IQ classification and proposed different category names from those used by Lewis Terman.

The third revision (Form L-M) in 1960 of the Stanford–Binet IQ test used the deviation scoring pioneered by David Wechsler.

David Freides, reviewing the Stanford–Binet Third Revision in 1970 for the Buros Seventh Mental Measurements Yearbook (published in 1972), commented that the test was obsolete by that year.

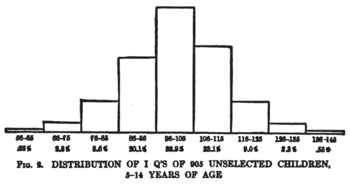

The test's manual included information about how the actual percentage of people in the norming sample scoring at various levels compared to theoretical expectations.

[77] Psychologists point out that evidence from IQ testing should always be used with other assessment evidence in mind: "In the end, any and all interpretations of test performance gain diagnostic meaning when they are corroborated by other data sources and when they are empirically or logically related to the area or areas of difficulty specified in the referral.

[79] Historically, terms for intellectual disability eventually became perceived as an insult, in a process commonly known as the euphemism treadmill.

[65][95] In 1939, Wechsler wrote "we are rather hesitant about calling a person a genius on the basis of a single intelligence test score.

"[96] The Terman longitudinal study in California eventually provided historical evidence on how genius is related to IQ scores.

[100][101] Based on the historical findings of the Terman study and on biographical examples such as Richard Feynman, who had an IQ of 125 and went on to win the Nobel Prize in physics and become widely known as a genius,[102][103] the current view of psychologists and other scholars[who?]

[106] Five levels of giftedness have been suggested to differentiate the vast difference in abilities that exists between children on varying ends of the gifted spectrum.

All longitudinal studies of IQ have shown that test-takers can bounce up and down in score, and thus switch up and down in rank order as compared to one another, over the course of childhood.

IQ classification categories such as "profoundly gifted" are those based on the obsolete Stanford–Binet Third Revision (Form L-M) test.