IRT Powerhouse

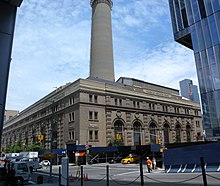

The IRT Powerhouse is on the border of the Hell's Kitchen and Riverside South neighborhoods on the West Side of Manhattan in New York City.

[8] The structural design is largely attributed to William C. Phelps, who had also been involved in constructing the Manhattan Railway Company's 74th Street Power Station between 1899 and 1901.

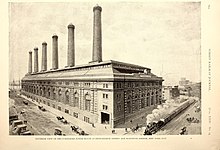

According to an IRT history, the directors decided on "an ornate style of treatment" similar to that of other civic projects of the time, while also rendering the building "architecturally attractive".

[11] The powerhouse provided power for the original subway line of the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT).

It and served as an aboveground focal point for the system, akin to Grand Central Terminal or St Pancras railway station.

[27] The most elaborately designed section of the building's facade is the eastern elevation facing Eleventh Avenue, which consists of eight bays.

[19] The northernmost bay, the furthest right along the Eleventh Avenue facade, contains the original main entrance, a rectangular doorway with a classically designed frame.

Between the facade and the sidewalk is a planting bed surrounded by an iron railing; the space originally contained a sunken basement court.

On both facades, each bay is separated by pairs of rusticated brick pilasters, which contain simple bands placed at regular intervals.

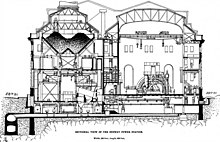

[17][34] In the engine house, a secondary floor surface of slate slabs on brick partitions is placed atop the concrete arches.

[31] The original chimneys were supported by platforms of 24-inch (610 mm) I-beams and a system of plate girders 8 feet (240 cm) deep.

[43] Five of the boiler/engine units were identical; the sixth had a steam turbine plant, installed to power the generator for lighting the subway tunnels.

The layout permitted a higher, well-lit boiler room, which helped reduce temperature extremes and the risks caused by escaping steam.

As built, there were nine alternating current generators of the flywheel type, each of which had a capacity of 5,000 kilowatts (6,700 hp), making 75 rotations per minute.

[68] Planning for the city's first subway line dates to the Rapid Transit Act, authorized by the New York State Legislature in 1894.

It needed easy access to transportation lines for coal delivery, as well as a nearby supply of water for boilers and steam condensing, which made a riverside location optimal.

[4][79][80] After buying the land for the powerhouse, Belmont, Deyo, McDonald, and van Vleck went to Europe for one month to research and observe railways and power infrastructure there.

[84] The powerhouse was originally supposed to be made entirely of concrete, but the IRT decided to use brick in March 1902 after bricklayers threatened to strike.

[81] By the end of 1903, the subway was nearly completed, but the Board of Rapid Transit Railroad Commissioners said that the labor strikes were holding up the system's opening.

[92] When the subcontractors installing the 59th Street plant's electrical and mechanical equipment hired nonunion workers, the labor unions threatened another strike in January 1904,[93][94] which was averted through negotiations.

[95][96] The Real Estate Record and Guide reported in April 1904 that, despite a bricklayers' strike, over four hundred workers were employed in constructing the powerhouse, and most of the building had been completed except for the western end.

[107][108] After the IRT added four boilers with underfeed stokers to the 59th Street plant in 1924, no major upgrades were carried out for the following sixteen years.

[3] By then, the obsolete boilers at the 59th Street plant were causing trains to run at slower speeds due to decreased output.

[122] Another recommendation was made to Wagner in April 1958, in which Con Ed would buy the plants for $123 million,[123] and the NYCTA dropped its opposition upon receiving assurances that the fare would be preserved.

[124] Con Ed made another offer in February 1959 in which it would pay about $126 million for the plants;[125] the deal was approved by the New York City Board of Estimate the next month.

[136] Walker O. Cain, an architect speaking on behalf of Con Ed, testified that it was unclear whether Stanford White's firm was involved with the construction of the other facades.

[3] The LPC held another landmark hearing in 1990, in which several preservation groups and Manhattan Community Board 4 supported designation.

[140][145] Accordingly, the LPC tabled the designation while it worked with Con Ed to determine how the building could be preserved while remaining in operation.

[150] Oil deliveries to Pier 58 had declined over the years, and the 59th Street steam plant relied increasingly on a natural-gas pipeline.

[21] Clifton Hood, author of a 2004 book about the history of the New York City Subway, described it as "a classical temple that paid homage to modern industry".