IRT Sixth Avenue Line

[2] Due to its central location in Manhattan and the inversion of the usual relationship between street noise and height,[clarification needed] the Sixth Avenue El attracted artists; in addition to being the subject of several paintings by John French Sloan, it was also painted by Francis Criss and others.

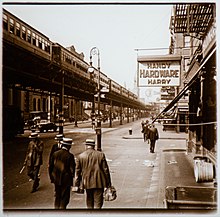

[3] As of 1934, the following services were being operated:[citation needed] As with many elevated railways in the city, the Sixth Avenue El made life difficult for those nearby.

It was noisy, it made buildings shake, and in the line's early years, it dropped ash, oil, and cinders on pedestrians below.

of commercial establishments and building owners along Sixth Avenue campaigned to have the El removed, on the grounds that it was depressing business and property values.

In 1936, work started on the underground Sixth Avenue Line, operated by the city as part of the Independent Subway System (IND).

In order to alleviate any concern that the scrap metal might be exported to the Japanese, demolition contractor Tom Harris, who had received $40,000 to demolish the structure provided affidavits to the New York City Council that none of the iron would leave the United States.

[12] At a meeting of the New York City Board of Estimate in 1942, Stanley M. Isaacs, the Manhattan Borough President, denied that steel from the El was sold to Japan.