Iambus (genre)

[6] Horace's Epodes on the other hand were mainly imitations of Archilochus[7] and, as with the Greek poet, his invectives took the forms both of private revenge and denunciation of social offenders.

A figure called "Iambe" is even mentioned in the Homeric Hymn to Demeter, employing language so abusive that the goddess forgets her sorrows and laughs instead.

Early dithyrambs were a "riotous affair"[13] and Archilochus was prominent in the controversial development of Dionyssian worship on Paros[14] (possibly in relation to phallic rites).

[18] A hundred years after Archilochus, Hipponax was composing choliambs, a deliberately awkward version of the iambic trimeter symbolizing mankind's imperfections and vices,[19] yet by then iambus seems to have been performed mainly for entertainment (our understanding of his work however might change significantly when and as more fragments are unearthed).

Its influence was already becoming evident in Athens by the fifth century BC, gradually changing the nature of poetry from a performance before a local group to a literary artifact with an international reach.

[25] Iambus was taken up as a political weapon by some public figures in Rome, such as Cato the Elder, who, in an account by Plutarch: ... betook himself to iambic verse, and heaped much scornful abuse upon Scipio, adopting the bitter tone of Archilochus, but avoiding his license and puerility.

[26]Neoteric poets such as Catullus combined a native tradition of satirical epigram with Hipponax's pungent invective to form neatly crafted, personal attacks.

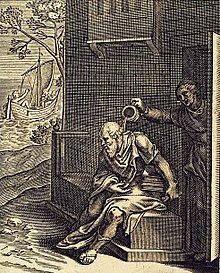

[28] Horace nominally modelled his Epodes on the work of Archilochus but he mainly followed the example of Callimachus, relying on painstaking craftsmanship rather than instinctive vitriol[29] and broadening the range of the genre.

Moreover, Horace's thematic variety is not without parallel among archaic poets such as Archilochus and Hipponax: the mood of the genre is meant to appear spontaneous and that inevitably led to some "hodepodge" contexts.

[31] Whatever his unique contribution may have been, Horace still managed to recreate something of the ancient spirit of the genre, alerting his companions to threats facing them as a group, in this case as Roman citizens of a doomed republic: In the midst of a crisis which could be seen as a result of the decline and failure of traditional Roman amicitia, Horace turned to a type of poetry whose function had been the affirmation of "friendship" in its community.

But he may have hoped that his iambi would somehow 'blame' his friends and fellow citizens into at least asking themselves quo ruitis [i.e. where are you careering to]?The nature of iambus changed from one epoch to another, as becomes obvious if we compare two poems that are otherwise very similar – Horace's Epode 10 (around 30 BC) and the "Strasbourg" papyrus, a fragment attributed either to Archilochus or Hipponax (seventh and sixth century respectively).

niger rudentis Eurus inverso mari fractosque remos differat; insurgat Aquilo, quantus altis montibus frangit trementis ilices;

et illa non virilis eiulatio preces et aversum ad Iovem, Ionius udo cum remugiens sinus Noto carinam ruperit!

If then the rich spoil, scattered round the curving shore, Lies at the pleasure of the gulls, There will be sacrifices of a lusty goat And lamb in honour of the Winds.

He could represent an imaginary scapegoat intended to avert the gods' anger from the poet's circle of 'friends', a device common in the archaic iambus of Hipponax and Archilochus: in this case, the "friends" may be understood to be Roman citizens at a time of social and political decay.

[35] A fictional Mevius would also be consistent with iambus as a mere literary topic, where Horace makes up for the lack of any real context by adding artistic values, in the Hellenistic manner.

This change in addressee is preceded by a mythological episode taken from the heroic Ajax legend, occurring exactly in the middle of the poem (lines 11–14), where it functions as a sort of piano nobile, with curses before and predictions afterwards.

The papyrus includes, among its tattered portions, an incomplete name (Ἱππωνά.., Hippona..), which seems to support Blass's identification since Hipponax often mentions himself by name in his extant work.

..... κύματι πλαζόμενος· κἀν Σαλμυδησσῶι γυμνὸν εὐφρονέστατα Θρήϊκες ἀκρόκομοι λάβοιεν - ἔνθα πόλλ᾽ ἀναπλήσει κακὰ δούλιον ἄρτον ἔδων - ῥίγει πεπηγότ᾽ αὐτόν· ἐκ δὲ τοῦ χνόου φυκία πόλλ᾽ ἐπέχοι, κροτέοι δ᾽ ὀδόντας, ὡς κύων ἐπὶ στόμα κείμενος ἀκρασίηι ἄκρον παρὰ ῥηγμῖνα κυμα[...] ταῦτ᾽ ἐθέλοιμ᾽ ἂν ἰδεῖν, ὅς μ᾽ ἠδίκησε, λὰξ δ᾽ ἐφ᾽ ὁρκίοισ᾽ ἔβη, τὸ πρὶν ἑταῖρος ἐών.

[42] .... Drifting about in the swell; When he comes nude to Salmydessus, may the kind Thracians, their hair in a bun, Take him in hand – there he shall have his fill of woe, Slavishly eating his bread – Stiff with the freezing cold; emerging from the froth, Clung to by piles of seaweed, May he lie like a dog face-down on chattering teeth, Laid low by his feebleness, Sprawled at the breakers' edge, still licked at by the surf!

Meanings flow clearly and naturally with the simple meter, except in one place, marked with a "parenthesis" or endash, where emotions get ahead of the poet's control as he anticipates years of suffering for his former friend.

Images seem to tumble from his excited mind but nothing is superfluous and his control of the material is shown for example in his use of irony when referring to the great kindness of the savage Thracians, their hair neatly dressed, in contrast to his nude friend.

In this poem fierce hatred mingled with contempt finds a powerful voice, and yet, with so much passion, every phrase and every sentence is kept strictly under the control of a masterly mind.

Every detail, the surf, the seaweed, the dog, the wretched man's frozen body, is there, life-like, or rather in even sharper outlines than they would appear to us in actual life.