Iapetus (moon)

When first discovered, Iapetus was among the four Saturnian moons labelled the Sidera Lodoicea by their discoverer Giovanni Cassini after King Louis XIV (the other three were Tethys, Dione and Rhea).

[17] Geological features on Iapetus are generally named after characters and places from the French epic poem The Song of Roland.

Iapetus is heavily cratered, and Cassini images have revealed large impact basins, at least five of which are over 350 km (220 mi) wide.

The original dark material is believed to have come from outside Iapetus, but now it consists principally of lag from the sublimation (evaporation) of ice from the warmer areas of the moon's surface, further darkened by exposure to sunlight.

[27][28][29] It contains organic compounds similar to the substances found in primitive meteorites or on the surfaces of comets; Earth-based observations have shown it to be carbonaceous, and it probably includes cyano-compounds such as frozen hydrogen cyanide polymers.

[30] The color dichotomy of scattered patches of light and dark material in the transition zone between Cassini Regio and the bright areas exists at very small scales, down to the imaging resolution of 30 metres (98 ft).

one foot) thick at least in some areas,[32] according to Cassini radar imaging and the fact that very small meteor impacts have punched through to the ice underneath.

[29][34] The difference in temperature means that ice preferentially sublimates from Cassini Regio, and deposits in the bright areas and especially at the even colder poles.

The redistribution of ice is facilitated by Iapetus's weak gravity, which means that at ambient temperatures a water molecule can migrate from one hemisphere to the other in just a few hops.

The initial dark material is thought to have been debris blasted by meteors off small outer moons in retrograde orbits and swept up by the leading hemisphere of Iapetus.

[28][29] In support of the hypothesis, simple numerical models of the exogenic deposition and thermal water redistribution processes can closely predict the two-toned appearance of Iapetus.

The discovery of a tenuous disk of material in the plane of and just inside Phoebe's orbit was announced on 6 October 2009,[37] supporting the model.

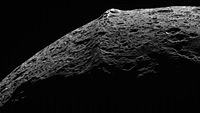

[40] Peaks in the ridge rise more than 20 km (12 mi) above the surrounding plains, making them some of the tallest mountains in the Solar System.

[43] The first spacecraft to visit Saturn, Pioneer 11, did not provide any images of Iapetus and it came no closer than 1,030,000 km (640,000 mi) from the moon.

Voyager 1 arrived at Saturn on November 12, 1980, and it became the first probe to return pictures of Iapetus that clearly show the moon's two-tone appearance from a distance of 2,480,000 km (1,540,000 mi)[46] as it was exiting the Saturnian system.

[47] Voyager 2 became the next probe to visit Saturn on August 22, 1981, and made its closest approach to Iapetus at a distance of 909,000 km (565,000 mi).

[49] It took photos of Iapetus's north pole as it entered the Saturnian system [50]- opposite the approach direction of Voyager 1.

Cassini made its first targeted flyby of Iapetus on Dec. 31, 2004, at a distance of 123,400 km (76,700 mi) around the time when the spacecraft was settling in its orbit around Saturn.

Cassini made a second flyby of Iapetus on November 12, 2005, at a distance of 415,000 km (258,000 mi),[53] also without crossing the moon's orbit.

[54][55] The fourth flyby happened on April 8, 2006, at a distance of approximately 866,000 km (538,000 mi), and this time, Cassini crossed Iapetus' orbit.