Ibn Butlan

Born in Baghdad, the erstwhile capital city of the Abbasid Caliphate, he travelled throughout Mesopotamia, Syria, Egypt, and Anatolia, during which time he practiced medicine, studied, wrote, and engaged in intellectual debates—most famously the Battle of the Physicians[a] with the Egyptian polymath Ibn Riḍwān.

After his time in Constantinople, Ibn Buṭlān remained in the Byzantine Empire and eventually became a monk for the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch amidst the end of the Macedonian Renaissance.

[e][f][10][11][3][12][13][14] Translations of Taqwīm aṣ-Ṣiḥḥa into Latin are preserved in many manuscripts from the early modern period, and are thought to illustrate the relationship between medieval Europe and the Arab world in the field of medicine.

Despite increased European contact with Egypt and Syria through the Crusades and trade into the 16th century, there are no Latin translations of Arabic medical texts after Ibn Buṭlān's era.

[15][16] Although he lived during a period when non-Muslims—the so-called People of the Pact,[g] who were originally Jews, Christians, and Sabians—dominated the medical profession in the Arab world,[h] Ibn Buṭlān is noteworthy for being one of only a few non-Muslim physicians from the region about whom enough is known to paint a detailed biography.

Documents like the Cairo Geniza, a collection of Jewish manuscript fragments, provide scientific records about the medical practices of such physicians, but lack reliable information outside of that to create detailed biographies about them and to describe their perception and role within society, thus proving Ibn Buṭlān as an important exception.

[24][53] The impression he left in northern Syria was so great that he became a notable figure in the local oral canon, three of these stories were recorded by Usāma ibn Munqiḏ in his Kitab al-Iʿtibār.

[70][65][31] Ibn Buṭlān would go on to condemn Monophysite beliefs in his work The Physicians' Banquet, a possible reason for the Aleppine Armenian community's staunch dislike for him long after his stay.

[r][30][73] Unlike in the rest of northern Syria, his legacy in the Christian community of Aleppo was not a positive one of a legendary medical sage; instead, its members recited offensive poems about him.

[92][99][100] And yet this satirical text also makes the defamatory suggestion all decent and educated persons of the city despised, the old physician, whom Conrad understands to be Ibn Riḍwān.

He had his break when he was able to substitute for a friend of his who worked as a physician and began to pursue medicine with much determination; he ended up gaining a position as the chief physician of the court, being the successor to Nasṭās ibn Ǧuraiǧ [ar], in addition to amassing a large number of students, a large personal medical library in an addition to a monetary fortune stemming from his real estate investments in the city.

Self-learning was equally regarded as a source of education compared to learning from a teacher at an institution, therefore social standing and one's reputation were the primary basis of a successful career in medicine.

It occurred in response to Ibn Buṭlān's attempt to improve his reputation among the educated upper class of Cairo with the assumed intention of gaining a maecenas.

This subject would have been of much interest in Cairo at the time as the city had a large poultry industry, known for its well documented widespread use of artificial egg incubation in so called "laying-hen factories".

[ah][121][41] Some scholars[ai] claim that Ibn Buṭlān would give his view of events though long after having left Egypt in a satirical work they identify as quasi-autobiographical, The Physicians' Banquet.

[24] Schacht and Meyerhof see the origins of the conflict as personal in nature but its dimensions as helpful in illustrating the reception of Greek and Syriac texts in the Arab world.

They conclude Ibn Buṭlān to be better educated in a broader variety of fields and to contribute more original ideas in his thinking, incorporating newer approaches like those of ar-Razī.

[127] On the 5th of August that year he reports about a number of earth quakes which had occurred in Byzantine territory, destroying a fortress and a church, numerous farms, and bringing forth hot springs and a swamp, causing the inhabitants of the affected places to lose all their belongings and flee to cities like Antioch.

[24] According to Ibn Abī Uṣaibiʿa he authored The Physicians' Banquet in the monastery[ao] in Constantiople, but Kennedy speculates that most of the work was written prior to his departure from Egypt.

[135] In the treatise itself he comments on the low level of medical knowledge in the town, though as some scholars[ap] regard the work as allegorical for his experiences in Cairo this might not be considered a neutral report.

Namely, Seth's uncredited reception of Buṭlān's Taqwīm aṣ-Ṣiḥḥa in form of a partial translation in his work On the Handbook of Health by the Balance of the Six Causes.

He sees that Ibn Buṭlān's approach in his essay, which seems to focus on reconciliation between the two conflicting sides, echoes the position of the Greek Orthodox Patriarch Peter III of Antioch.

Oltean argues based on the lack of a Church of the East presence in Antioch and the troubled state of the Jacobite Armenian Monophysite community in the city and his mockery of their creed in the Banquet of the Priests, that he must have joined a Melkite monastery there.

This lack of recordings was used by George Sarton to suggest that "the failure of medieval Europeans and Arabs to recognise such phenomena was not due to any difficulty in seeing them, but to prejudice and spiritual inertia connected with the groundless belief in celestial perfection".

Ibn Buṭlān was not a professional astronomer nor an astrologer, rather he was a physician operating according to the tradition of Galen and Hippocrates both of whom believed in a connection between cosmic and telluric events, illness and natural catastrophes.

While he engages in astronomy, he does not express any confidence in this science, in fact in matters were astrological and physiological or pathological insight collide, the latter two always prevail in his analyses, something which also representative of the attitudes of most of his contemporaries.

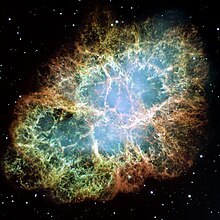

I quote the following from what he wrote in his own hand about this matter:One of the famous calamities of our time was that which occurred when the star leaving marks (Arabic: الكوكب الأثاري, romanized: al-Kaukab al-Aṯārī) rose in Gemini in the year 446.

The kings of the earth were in disarray, and war, inflation of prices, and pestilence proliferated, and Ptolemy's words that when there is a conjunction of Saturn and Mars in Cancer the world will be in upheaval proved true.

[62]Though he connects his observations to predictions by Ptolemy about a comet, what is termed in this report a 'star leaving marks'[at] is, in fact, a supernova and the terminology used resembles that used by Ibn Riḍwān Arabic: الأثر, romanized: al-Aṯār, lit.

'[av] Ibn Buṭlān's comments about the level of Nile failing to rise refer to the period prior to its annual flooding during midsummer and hence also speak of the season during which we know the supernova occurred.