Icelandic Americans

It is generally accepted that the Norse settlers in Greenland founded the settlement of L'Anse aux Meadows in Vinland, their name for what is now Newfoundland, Canada.

Many Icelandic men took laboring jobs as unskilled factory workers and woodcutters, or as dockworkers in Milwaukee when they first arrived.

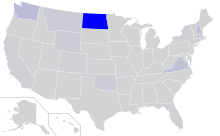

Those coming to the United States settled primarily in the upper Midwest, especially Wisconsin, Minnesota, and the Dakota Territories.

[2] In 1870, four Icelanders left for Milwaukee, eventually settling on Washington Island in Lake Michigan, just off the Green Bay peninsula.

They managed to interest the United States government enough to assist them in visiting the proposed Alaskan site.

Some of these found employment easier to get on Puget Sound in the state of Washington where they worked in the fishing and boatbuilding trades.

Moving south to the United States, they joined more recent Icelandic immigrants in the northeastern section of the Dakota Territory.

[5] According to historian Gunnar Karlsson, "migration from Iceland is unique in that most went to Canada, whereas from most or all other European countries the majority went to the United States.

[7] Settlement patterns during the second half of the 19th century placed Icelanders mainly in the upper Midwestern states of Minnesota and Wisconsin, and in the Dakota Territory.

Early 20th-century industrialization transformed the United States from an agrarian culture into an urban one, affecting traditionally agrarian-based Icelandic communities.

The 1990 Census of the U.S. Department of Commerce revealed a total count of Icelandic-Americans and Icelandic nationals living in the United States as 40,529.

[5] According to the 2000 U.S. Census, there were 42,716 Americans that claimed partial or full Icelandic ancestry, of which 6,760 were born outside of the United States.

Few studies in English have concentrated on Icelanders, and many reference books have omitted them altogether from general accounts of ethnic distinctions such as holidays, customs, and dress.

[5] Nonetheless, strong in their self-identity, Icelanders have from the beginning eagerly adopted new customs in the United States, learning English, holding public office, and integrating into the general culture.

At the same time, they have retained a strong sense of ethnic pride, as evidenced in the large number of Icelandic-American organizations in existence throughout the United States since the founding of the Icelandic National League in 1919.

Toward the end of the 20th century, widespread attention to multiculturalism kindled interest in understanding ethnic differences, spurring many Icelanders to reclaim their heritage.