Ideas of European unity before 1948

[1][2] Military unions of "Christian European powers" in the medieval and early modern period were directed against Muslim expansion, namely during the Crusades and the Reconquista.

[3] In the Renaissance, medieval trade flourished in organisations like the Hanseatic League, stretching from English towns like Boston and London, to Frankfurt, Stockholm and Riga.

Martin Luther nailed a list of demands to the church door of Wittenberg, King Henry VIII declared a unilateral split from Rome with the Act of Supremacy 1534, and conflicts flared across the Holy Roman Empire until the Peace of Augsburg 1555 guaranteed each principality the right to its chosen religion (cuius regio, eius religio).

Even then, the English Civil War broke out and only ended with the Glorious Revolution of 1688, by Parliament inviting William and Mary from Hannover to the throne, and passing the Bill of Rights 1689.

In the 1800s, a customs union under Napoleon Bonaparte's Continental system was promulgated in November 1806 as an embargo of British goods in the interests of the French hegemony.

Hugo used the term United States of Europe (French: États-Unis d'Europe) during a speech at the International Peace Congress organised by Mazzini, held in Paris in 1849.

The tree to this day grows in the gardens of Maison de Hauteville, St. Peter Port, Guernsey, Victor Hugo's residence during his exile from France.

[13] The Italian philosopher Carlo Cattaneo wrote "The ocean is rough and whirling, and the currents go to two possible endings: the autocrat, or the United States of Europe".

As part of 19th-century concerns about an ailing Europe and the threat posed by the Mahdi, the Polish writer Theodore de Korwin Szymanowski's original contribution was to focus not on nationalism, sovereignty, and federation, but foremost on economics, statistics, monetary policy, and parliamentary reform.

World War I devastated Europe's society and economy, and the Versailles Treaty failed to establish a workable international system in the League of Nations, any European integration, and imposed punishing terms of reparation payments for the losing countries.

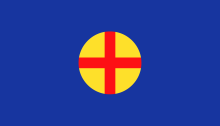

With a conservative vision of Europe, the Austrian Count Richard von Coudenhove-Kalergi founded the Pan-Europa movement in 1923, hosting the First Paneuropean Congress in Vienna in 1926, and which contained 8000 members by the time of the 1929 Wall Street crash.

Many eminent economists, aware that the economic race-to-the-bottom between states was creating ever greater instability, supported the view: these included John Maynard Keynes.

The French political scientist and economist Bertrand Jouvenel remembered a widespread mood after 1924 calling for a "harmonisation of national interests along the lines of European union, for the purpose of common prosperity".

[17] The Spanish philosopher and politician, Ortega y Gasset, expressed a position shared by many within Republican Spain: "European unity is no fantasy, but reality itself; and the fantasy is precisely the opposite: the belief that France, Germany, Italy or Spain are substantive & independent realities.”[18] Eleftherios Venizelos, Prime Minister of Greece, outlined his government's support in a 1929 speech by saying that "the United States of Europe will represent, even without Russia, a power strong enough to advance, up to a satisfactory point, the prosperity of the other continents as well".

[19] Between the two world wars, the Polish statesman Józef Piłsudski envisaged the idea of a European federation that he called Międzymorze ("Intersea" or "Between-seas"), known in English as Intermarium, which was a Polish-oriented version of Mitteleuropa, though devised according to the principle of cooperation rather than subjugation.

The Land Beyond the Forest Louis C. Cornish[20][21] described how Teleki, under constant surveillance by the German Gestapo during 1941, sent a secret communication to contacts in America.

"[22] Teleki received no response from the Americans to his ideas and when German troops moved through Hungary on 2–3 April 1941 during the invasion of Yugoslavia, he committed suicide.

[23] The countries proposed for inclusion were Germany, Italy, France, Denmark, Norway, Finland, Slovakia, Hungary, Bulgaria, Romania, Croatia, Serbia, Sweden, Greece and Spain.

Although this fact has been used to insinuate the charge of fascism in the EU, the idea is much older than the Nazis, foreseen by John Maynard Keynes, and later by Winston Churchill and by various anti-Nazi resistance movements.

[32][33] The growing rift among the Four Powers became evident as a result of the rigged 1947 Polish legislative election which constituted an open breach of the Yalta Agreement, followed by the announcement of the Truman Doctrine on 12 March 1947.

On 4 March 1947 France and the United Kingdom signed the Treaty of Dunkirk for mutual assistance in the event of future military aggression in the aftermath of World War II against any of the pair.

The rationale for the treaty was the threat of a potential future military attack, specifically a Soviet one in practice, though publicised under the disguise of a German one, according to the official statements.

Immediately following the February 1948 coup d'état by the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, the London Six-Power Conference was held, resulting in the Soviet boycott of the Allied Control Council and its incapacitation, an event marking the beginning of the Cold War.