Ignoramus et ignorabimus

[5][6] On 8 September 1930, Hilbert elaborated his opinion in a celebrated address to the Society of German Scientists and Physicians, in Königsberg:[7] We must not believe those, who today, with philosophical bearing and deliberative tone, prophesy the fall of culture and accept the ignorabimus.

While this does not exclude that the question can be answered unambiguously in another system, the incompleteness theorems are generally taken to imply that Hilbert's hopes for proving the consistency of mathematics using purely finitistic methods were unfounded.

[9] As this excludes the possibility of an absolute proof of consistency, there must always remain an ineliminable degree of insecurity about the foundations of mathematics: we will never be capable of knowing, once and for all, with a certainty unimpeachable even by the most stout skepticism, that there is no contradiction in our basic theories.

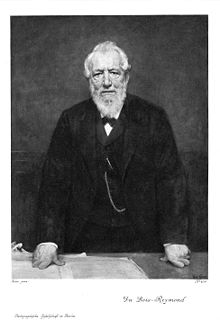

The sociologist Wolf Lepenies discussed the Ignorabimus with the opinion that du Bois-Reymond was not really pessimistic about science:[10] ... it is in fact an incredibly self-confident support for scientific hubris masked as modesty ...This was in regards to Friedrich Wolters, one of the members of the literary group "George-Kreis".

The Quarterly Review also regarded the maxim as the ensign of agnosticism:[16]To the average citizen who reads as he runs, and who is unacquainted with any tongue save his native British, it may well appear that the Gospel of Unbelief, preached among us during the last half-century, has had its four Evangelists–the Quadrilateral, as they have been called, whose works and outworks, demilunes and frowning bastions, take the public eye, while above them floats the agnostic banner with its strange device, "Ignoramus et Ignorabimus."