Imjin War

With Toyotomi Hideyoshi's death in 1598, limited progress on land, and continued disruption of supply lines by the Joseon Navy, the Japanese forces in Korea were ordered to withdraw back to Japan by the new governing Council of Five Elders.

Both emerged during the 14th century after the end of the Yuan dynasty, embraced Confucian ideals in society, and faced similar threats (Jurchen people, who raided along the northern borders, and the Sino-Japanese wokou pirates, who pillaged coastal villages and trade ships),[44][45] Both had competing internal political factions, which would influence decisions made prior to and during the war.

[52] It is also suggested that Hideyoshi planned an invasion of China to fulfill the dreams of his late lord, Oda Nobunaga,[53] and to keep his newly formed state united against a common enemy, mitigating the possible threat of civil disorder or rebellion posed by the large number of now-idle samurai and soldiers, and by ambitious daimyōs who might have sought to usurp him.

Although it was [partly] due to there having been a century of peace and the people not being familiar with warfare that this happened, it was really because the Japanese had the use of muskets that could reach beyond several hundred paces, that always pierced what they struck, that came like the wind and the hail, and with which bows and arrows could not compare.

[130] Katō's battle standard was a white pennant which carried a message alleged to have been written by Nichiren himself reading Namu Myōhō Renge Kyō ("Hail to the Lotus of the Divine Law").

[67] Local officers were forbidden from responding to enemy activities and battles outside of their jurisdiction until a higher ranking general, appointed by the king's court, arrived with a newly mobilized army to take command, hindering flexibility.

[167] The Fourth Division, under the command of Mōri Yoshinari, set out eastward from the capital city of Hanseong in July, and captured a series of fortresses along the eastern coast from Anbyon to Samcheok.

[182] However, Yi Sun-sin, who held the post of the Left Naval Commander[n 3] of the Jeolla Province (which covers the western waters of Korea), successfully destroyed the Japanese ships transporting troops and supplies.

[182] When the Japanese troops landed at the port of Busan, Bak (also spelled Park) Hong, the Left Naval Commander of Gyeongsang Province, destroyed his entire fleet, his base, and all armaments and provisions, and fled.

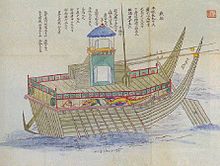

[192][195] In his report to King Seonjo, Admiral Yi wrote: "Previously, foreseeing the Japanese invasion, I had a turtle ship made...with a dragon's head, from whose mouth we could fire cannons, and with iron spikes on its back to pierce the enemy's feet when they tried to board.

The feigned retreat worked, with the Japanese following the Koreans to the open sea, and Yi wrote: Then our ships suddenly enveloped the enemy craft from the four directions, attacking them from both flanks at full speed.

[231] Ankokuji Ekei, a former Buddhist monk made into a general due to his role in the negotiations between Mōri Terumoto and Toyotomi Hideyoshi, led the units of the Sixth Division charged with the invasion of Jeolla Province.

[236] Hyujeong ended his appeal with a call for monks who were able-bodied to "put on the armor of mercy of Bodhisattvas, hold in hand the treasured sword to fell the devil, wield the lightning bolt of the Eight Deities, and come forward!".

[236] At least 8,000 monks responded to Hyujeong's call, some out of a sense of Korean patriotism and others motivated by a desire to improve the status of Buddhism, which suffered discrimination from a Sinophile court intent upon promoting Confucianism.

[236] In Chungcheong Province, the abbot Yeonggyu proved to be an active guerrilla leader and together with the Righteous Army of 1,100 commanded by Jo Heon attacked and defeated the Japanese at the Battle of Cheongju on 6 September 1592.

[246][247] The local governor at Liaodong eventually acted upon King Seonjo's request for aid following the capture of Pyongyang by sending a small force of 5,000 soldiers led by Zu Chengxun.

[256] The Korean warrior monks, led by Abbot Hyujeong, attacked the headquarters of Konishi Yuninaga on Moranbong, coming under heavy Japanese arquebus fire, taking hundreds of dead, but they persevered.

[240] Later that same day, the Chinese under Wu Weizhong joined the attack, and with a real danger that Konishi would be cut off from the rest of his army, So Yoshitoshi led a counterattack that rescued the Japanese forces from Moranbong.

Gwon Yul quickly advanced northwards, retaking Suwon and then swung north toward the fortress Haengjusanseong, a wooden stockade on a cliff over the Han River, where he would wait for Chinese reinforcements.

[265] Bolstered by the victory at the Battle of Byeokjegwan, Katō Kiyomasa and his army of 30,000 men advanced to the south of Hanseong to attack Haengjusanseong, an impressive mountain fortress that overlooked the surrounding area.

When the weather warmed, the road conditions in Korea also became terrible, as numerous letters from Song Yingchang and other Ming officers attest, which made resupplying from China itself also a tedious process.

Failing to gain a foothold during Katō Kiyomasa's Chinese campaign, and the near complete withdrawal of the Japanese forces during the first invasion, had established that the Korean peninsula was the more prudent and realistic objective.

Prior to this engagement, Bae Seol (1551–1599), a naval officer who did not submit to Won Gyun's leadership, kept thirteen panokseons under his command and out of the battle, instead escaping to the southwestern Korean coast.

Upon the start of the second invasion, the Ming Emperor was furious about the entire debacle of the peace talks and turned his wrath on many of its chief supporters; particularly Shi Xing, the Minister of War, who was removed from his position and jailed (he died several years later, in prison).

[306] Late one night, Ma Gui decided to order a general organized retreat of the allied forces, but soon confusion set in, and matters were further complicated by heavy rainfall and harassing attacks by the Japanese.

Noting the narrow geography of the area, Ming general Chen Lin, who led Deng Zilong and Yi Sun-sin,[315] made a surprise attack against the Japanese fleet, under the cover of darkness on 16 December 1598, using cannon and fire arrows.

[318] Realizing that the Shogunate would never agree to such a request, Sō Yoshitoshi sent a forged letter and a group of criminals instead; the great need to expel the Ming soldiers pushed Joseon into accepting and to send an emissary in 1608.

Falling tax revenues, troop desertions, a flow of foreign silver which brought unexpected problems in the Chinese economy, poor granary supervision and harsh weather eventually culminated in the collapse of the Ming Dynasty.

[327] However, the sinocentric tributary system that the Ming had defended continued to be maintained by the Qing, and ultimately, the war resulted in a maintenance of the status quo—with the re-establishment of trade and the normalization of relations between all three parties.

[318] After the immediate Japanese military threat was neutralized, Turnbull states that the Joseon desire for the Ming armies to quickly withdraw from Korean territory was a contributing factor to the pace of the eventual peace resolution.