Immigration to Brazil

Since then, some of those who entered the independent nation were immigrants, mainly Portuguese, Italians and Spaniards, but also Germans, Japanese, Poles, Lebanese, Syrians, Lithuanians, Ukrainians, Jews, Russians and many others.

Immigration increased pressure from the first end of the international slave trade to Brazil, after the expansion of the economy, especially in the period of large coffee plantations in the state of São Paulo.

[8][9] The Portuguese settled in the whole territory, initially remaining near the coast, except in the region of São Paulo, from where the bandeirantes would spread into the hinterland.

In 1812, settlers from the Azores were brought to Espírito Santo and in 1819, Swiss to Nova Friburgo, Rio de Janeiro.

[13] From 1824, immigrants from Central Europe started to populate what is nowadays the region of São Leopoldo, in the province of Rio Grande do Sul.

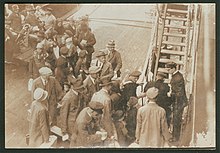

[17] During this period, immigration was much more intense: large numbers of Europeans, especially Italians, started to be brought to the country to work in the harvest of coffee.

[19] Brazil's receiving structure, legislation and settlement policies for immigrants were much less organized than in Canada and the United States at the time.

At the time, the region of São Paulo was undergoing a process of economic boom, linked to the expansion of the cultivation of coffee, and consequently needed increased amounts of labour.

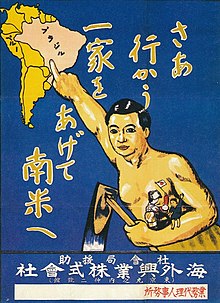

Thus the paulista oligarchy sought to attract new workers from abroad, by passing provincial legislation and pressing the Imperial government to organise immigration.

In consequence of the Prinetti Decree of 1902, that forbade subsidised emigration to Brazil, Italian immigration had, at this stage, a drastic reduction: their average annual entries from 1887 to 1903 was 58,000.

By 1934, over 40% of the coffee production in São Paulo was produced by the 14.5 percent foreign population of the state, showing their entrepreneurial spirit and ambition.

[23] With the radicalization of the political situation in Europe, the end of the demographic crisis, the decadence of coffee culture, the Revolution of 1930 and the consequent rise of a nationalist government, immigration to Brazil was significantly reduced.

During the 1970s Brazil received about 32,000 Lebanese immigrants escaping the civil war, as well as smaller numbers of Palestinians and Syrians.

In 2009, nationals from signatory States of the Mercosur Residence Agreement, which include eight countries, such as Argentina, Uruguay, Chile, etc., may establish temporary residence in Brazil: In 2019, in his first year of government, the president Jair Bolsonaro, announced the end of the tourist visa requirement to the United States, Canada, Australia and Japan.

[39] In March 2023, president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, announced the return of the visa requirement to the United States, Canada, Japan and Australia.

[40] A foreigner with a permanent resident visa has nearly all of the same rights as a Brazilian citizen, such as access to health and education services in Brazil, in addition to being able to open a business, bank account, obtain a driver's license, among others.

The Union has exclusive power to legislate with respect to: XIII - nationality, citizenship and naturalization; XV - emigration, immigration, entry, extradition and expulsion of foreigners; Article 112.

Are conditions for the granting of naturalization: I - civilian capacity, according to Brazilian law; II - to be registered as permanent resident in Brazil; III - continuous residence in the territory for a minimum period of 4 (four) years immediately preceding the application for naturalization; IV - read and write the Portuguese language, considering the conditions of naturalizing; V - exercise of occupation or possession of sufficient assets to maintain itself and the family; VI - proper procedure; VII - no complaint, indictment in Brazil or abroad for a felony that is threatened in minimum sentence of imprisonment, abstractly considered, more than 1 (one) year; VIII - good health.

[46] Some areas of the city remained almost exclusively settled by Italians until the arrival of waves of migrants from other parts of Brazil, particularly from the Northeast, starting in the late 1920s.

According to historian Samuel H. Lowrie, in the early 20th century the society of São Paulo was divided in three classes:[46] According to Lowrie, the fact that Brazil already had a long history of racial mixture and that most of the immigrants in São Paulo came from Latin European countries, reduced the cases of racism and mutual intolerance.

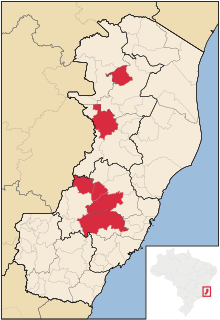

As a result of the great internal migration of people in Rio Grande do Sul, Germans and second generation descendants started to move to other areas of the province.

Arriving in larger numbers than Germans, in the 1870s, groups of Italians started settling northeast Rio Grande do Sul.

The second is based on the work of Arthur Neiva, who supposes the return rate for Brazil was higher than that of the United States (30%) but lower than that of Argentina (47%).

[75] Clevelário believes the most probable number to be close to 18%, higher than Mortara's previous estimate of 1947.: Abstract, p. 71 According to the Census of 1872, there were 9,930,478 people in Brazil, of which 3,787,289 (38.14%) Whites, 3,380,172 (34.04%) Pardos, 1.954.452 (19.68%) Blacks, and 386,955 (3.90%) Caboclos.

This research interviewed about 90,000 people in six metropolitan regions (São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Porto Alegre, Belo Horizonte, Salvador, and Recife).

Spaniards started arriving about the same time as the Italians, but came in more steady pace, which means that, in average, they represent a more recent immigration.

When the number of immigrants is compared to the findings of the July 1998 PME, the results are different: Here the correct order is reestablished, except for the Arabs appearing with a lower descendant/immigrant rate than the Japanese.

Nevertheless, different analysts often dispute how truthful this image is and, although openly xenophobic manifestation were uncommon, some scholars denounce it existence in more subtle ways.

[93] 1200 Venezuelans went back to their homeland as a result and the administration of President Michel Temer increased military personnel in the border.

In this century has grown a recent trend of co-official languages in cities populated by immigrants (such as Italian and German) or indigenous in the north, both with support from the Ministry of Tourism, as was recently established in Santa Maria de Jetibá, Pomerode and Vila Pavão,[96] where German also has co-official status.