Japanese Brazilians

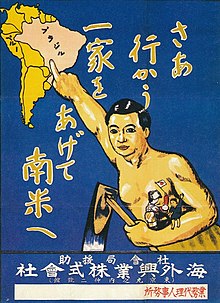

[12] Consequently, the São Paulo government sought new sources of labor from other countries, including Japan, and Japanese immigration to Brazil developed in this context.

[16] Japan had been isolated from the rest of the world during the 265 years of the Edo period (Tokugawa Shogunate), without wars, epidemics brought in from abroad or emigration.

The end of feudalism in Japan generated great poverty in the rural population, so many Japanese people began to emigrate in search of better living conditions.

About half of these immigrants were Okinawans from southern Okinawa, who had faced 29 years of oppression by the Japanese government following the Ryukyu Islands's annexation, becoming the first Ryukyuan Brazilians.

[28] Because multiple persons necessitated monetary support in these familial units, Japanese immigrants found it nearly impossible to return home to Japan even years after emigrating to Brazil.

Indebted and subjected to hours of exhaustive work, often suffering physical violence, suicide, yonige (to escape at night), and strikes were some of the attitudes taken by many Japanese because of the exploitation on coffee farms.

[35] With Brazil under the leadership of Getúlio Vargas and the Empire of Japan involved on the Axis side in World War II, Japanese Brazilians became more isolated from their mother country.

On 28 July 1921, representatives Andrade Bezerra and Cincinato Braga proposed a law whose Article 1 provided: "The immigration of individuals from the black race to Brazil is prohibited."

The Constitution of 1934 had a legal provision about the subject: "The concentration of immigrants anywhere in the country is prohibited, the law should govern the selection, location and assimilation of the alien".

The Brazilian magazine "O Malho" in its edition of 5 December 1908 issued a charge of Japanese immigrants with the following legend: "The government of São Paulo is stubborn.

[38] In 1941, the Brazilian Minister of Justice, Francisco Campos, defended the ban on admission of 400 Japanese immigrants in São Paulo and wrote: "their despicable standard of living is a brutal competition with the country's worker; their selfishness, their bad faith, their refractory character, make them a huge ethnic and cultural cyst located in the richest regions of Brazil".

On 10 July 1943, approximately 10,000 Japanese and German and Italian immigrants who lived in Santos had 24 hours to close their homes and businesses and move away from the Brazilian coast.

[38] During the National Constituent Assembly of 1946, the representative of Rio de Janeiro Miguel Couto Filho proposed Amendments to the Constitution as follows: "It is prohibited the entry of Japanese immigrants of any age and any origin in the country".

Senator Fernando de Melo Viana, who chaired the session of the Constituent Assembly, had the casting vote and rejected the constitutional amendment.

As the vast majority of families that moved to São Paulo and cities in Paraná had few resources and were headed by first and second-generation Japanese, it was imperative that their business did not require a large initial investment or advanced knowledge of the Portuguese language.

According to anthropologist Célia Sakurai: "The business was convenient for the families, because they could live at the back of the dye shop and do all the work without having to hire employees.

[29] In the Brazilian urban environment, the Japanese began to work mainly in sectors related to agriculture, such as traders or owners of small stores, selling fruit, vegetables or fish.

Working with greengrocers and market stalls was facilitated by the contact that urban Japanese had with those who had stayed in the countryside, as suppliers were usually friends or relatives.

The custom was a Japanese tradition of delegating to the eldest son the continuation of the family activity and also the need to help pay for the studies of the younger siblings.

While the older ones worked, the younger siblings enrolled in technical courses, such as Accountancy, mainly because it was easier to deal with numbers than with the Portuguese language.

[41] According to the newspaper Gazeta do Povo, in Brazil "common sense is that Japanese descendants are studious, disciplined, do well at school, pass the admission exams more easily and, in most cases, have great affinity for the exact science careers".

These are teachings passed down by Meiji-era immigrants that have shaped the conduct of later generations in their approach to work and family, and in some way have helped create the image of Japanese descendants as "studious," "intelligent," and "disciplined.

In a rural environment, the proximity between community members and the strength of family relationships meant that Japanese traditions remained more alive.

According to this study, although Brazilian dishes predominate on the menu of members of the fourth generation, they maintain the habit of frequently eating gohan (Japanese white rice, without seasoning) and consuming soy sauce, greens and vegetables cooked in the traditional way.

Some practices linked to the cult of ancestors, one of the pillars of Buddhism and Shintoism, also survive: many of them keep the butsudan at home, an altar on which photos of the family's dead are placed, to whom relatives offer water, food and prayers.

[61] A study conducted in the Japanese Brazilian communities of Aliança and Fukuhaku, both in the state of São Paulo, released information on the language spoken by these people.

The legislation of 1990 was intended to select immigrants who entered Japan, giving a clear preference for Japanese descendants from South America, especially Brazil.

This population, attempting to maintain or improve their standard of living, began seeking better economic conditions in Japan, the country of their ancestors.

[78] These people were lured to Japan to work in areas that the Japanese refused (the so-called "three K": Kitsui, Kitanai and Kiken – hard, dirty and dangerous).

[104] Hiromi Shibata, a PhD student at the University of São Paulo, wrote the dissertation As escolas japonesas paulistas (1915–1945), published in 1997.