Immigration to New Zealand

Given the isolation of the archipelago, people generally do not come to New Zealand casually: one cannot wander across a border or gradually encroach on neighbouring land in order to reach remote South Pacific islands.

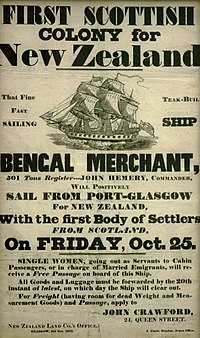

Settlement usually takes place deliberately, with waves of people transported from afar by successive boats or aeroplanes, and often landing in specific locales (rohe, colonies and provinces).

Only then did the original inhabitants need to distinguish themselves from the new arrivals, using the adjective "māori" which means "ordinary" or "indigenous" which later became a noun although the term New Zealand native was common until about 1890.

The establishment of British colonies in Australia from 1788 and the boom in whaling and sealing in the Southern Ocean brought many Europeans to the vicinity of New Zealand, with some settling.

[citation needed] Violence against European shipping, cannibalism and the lack of established law and order made settling in New Zealand a risky prospect.

Smaller numbers came directly from Great Britain, Ireland, Germany (forming the next biggest immigrant group after the British and Irish),[2] France, Portugal, the Netherlands, Denmark, The United States, and Canada.

Cargo carried on the Glentanner for New Zealand included coal, slate, lead sheet, wine, beer, cart components, salt, soap and passengers' personal goods.

[4] In the 1860s most migrants settled in the South Island due to gold discoveries and the availability of flat grass covered land for pastoral farming.

Given the prevailing social attitudes at the time, the practical effect of the legislation was to allow the Minister to pursue an immigration policy which gave preference to persons regarded as being of adequate racial characteristics – namely, those of European ancestry.

A Department of External Affairs memorandum in 1953 would state: "Our immigration is based firmly on the principle that we are and intend to remain a country of European development.

The decline of the New Zealand economy, marked by high inflation and rising unemployment, caused a net loss of population between 1976 and 1980, a trend that was only reversed in the 1980's.

[citation needed] The shift towards a skills-based immigration system resulted in a wide variety of ethnicities in New Zealand, with people from over 120 countries represented.

[citation needed] In December 2002, the minimum IELTS level for skilled migrants was raised from 5.5 to 6.5 in 2002, following concerns that immigrants who spoke English as a second language encountered difficulty getting jobs in their chosen fields.

The Department of Labour's sixth annual Migration Trends report showed a 21 per cent rise in work permits issued in the 2005/06-year compared with the previous year.

[20] In May 2008, Massey University economist Dr Greg Clydesdale released to the news media an extract of a report, Growing Pains, Evaluations and the Cost of Human Capital, which claimed that Pacific Islanders were "forming an underclass".

[21] The report, written by Dr Clydesdale for the "Academy of World Business, Marketing & Management Development 2008 Conference" in Brazil, and based on data from various government departments, provoked highly controversial debate.

[31] In May 2022, Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern announced that the Government would be introducing a new "green list" to attract migrants for "high-skilled" and "hard-to-fill" positions from 4 July 2022.

[35] On 8 August, the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment admitted that only nine nurses had applied for the Green List visa residency scheme by late July 2022.

In addition teachers and tradespeople including drain layers and motor mechanics were added to the work to residence immigration pathway.

The licensing managed by the Immigration Advisers Authority Official website establishes and monitors industry standards and sets requirements for continued professional development.

[42] New Zealand accepts 1000 refugees per year (set to grow to 1500 by 1 July 2020) in co-operation with the UNHCR with a strong focus on the Asia-Pacific region.

These raids controversially targeted Pasifika peoples; many of whom had migrated to the New Zealand during the 1950s and 1960s due to a demand for labour to fuel the country's economic development.

According to figures released by the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) in 2017, the top five nationalities with the highest number of overstayers in New Zealand were Tongans (2,498), Samoans (1,549), Chinese (1,529), Indians (1,310), and Malaysians (790).

Overstayers can appeal their deportation notices to the Immigration and Protection Tribunal which has granted residency on humanitarian grounds such as family connections to New Zealand.

[56][57] In February 2022, a report published by the Australian think tank Lowy Institute found that New Zealand had deported 1,040 people to the Pacific Islands between 2013 and 2018.

The report's author Jose Sousa-Santos argued that New Zealand, Australia and the United States' deportation policies were fuelling a spike in organised crime and drug trafficking in several Pacific countries including Samoa, Tonga, Fiji, Kiribati, Nauru, Tuvalu and Vanuatu.

The law allows the chief executive of the Department of Corrections to apply to a district court to impose special conditions on returning prisoners including submitting photographs and fingerprints.

In addition to boosting the methamphetamine black market, the Comanchero and Mongols used social media and luxury goods to recruit young people.

[66][67] On 20 December 2022, High Court Judge Cheryl Gwyn ruled in favour of a former 501 deportee known as "G," who successfully challenged the Government's authority to impose special conditions upon his return to New Zealand.

[63] On 21 December, the Crown Law Office appealed against Gwyn's High Court ruling, citing its implications on the monitoring regime established by the Returning Offenders (Management and Information) Act 2015.

Source: New Zealand Department of Labour [ 17 ]