New Zealand literature

Many New Zealand writers have obtained local and international renown over the years, including the short-story writers Katherine Mansfield, Frank Sargeson and Jacquie Sturm, novelists Janet Frame, Patricia Grace, Witi Ihimaera, Maurice Gee, Keri Hulme and Eleanor Catton, poets James K. Baxter, Fleur Adcock, Selina Tusitala Marsh and Hone Tuwhare, children's authors Margaret Mahy and Joy Cowley, historians Michael King and Judith Binney, and playwright Roger Hall.

Polynesian settlers began arriving in New Zealand in the late 13th or early 14th century, and became known as Māori developing a distinct culture, including oral myths, legends, poetry, songs (waiata), and prayers.

[3] Kendell, chief Hongi Hika, his nephew Waikato and linguist Samuel Lee developed a systematic written form of Māori language at Cambridge University in England in 1820.

[6][7] In New Zealand, as European settlers arrived, they collected many Māori oral stories and poems, which were translated into English and published, such as Polynesian Mythology (1855) by George Grey and Maori Fairy Tales (1908) by Johannes Andersen.

The term "Maoriland", proposed and often used as an alternative name for New Zealand around this time, became the centre of a literary movement in which colonialist writers were inspired by and adopted Māori traditions and legends.

[16] New Zealand's fourth premier, Alfred Domett, wrote an epic poem, Ranolf and Amohia: A South-Sea Day-Dream (1872), which was over 100,000 words long and described a romance between a shipwrecked European man and a Māori woman.

[23][24] New Zealand literature continued to develop in the early 20th century, with notable writers including the poet Blanche Edith Baughan and novelist Jane Mander.

[33] It was common at this time for writers, like Mansfield, to leave New Zealand and establish careers overseas: including Mulgan, Dan Davin, who joined the Oxford University Press, and journalist Geoffrey Cox.

[1] Writing was still largely a Pākehā endeavour at this time; many Māori were living in rural areas and recovering from the loss of their land and language, depopulation, and educational challenges.

[38] Curnow and Brasch were just two of their generation of poets who began their careers with Caxton Press in the 1930s, and had a major influence on New Zealand poetry; others in the group were A. R. D. Fairburn, R. A. K. Mason and Denis Glover.

[39] Their poems can be contrasted with the work of South African-born Robin Hyde, who was excluded from this nationalist group, but whose novel The Godwits Fly (1938) was considered a New Zealand classic and continuously in print until the 1980s.

[1] By the 1950s there were a wide range of outlets for local literature, such as the influential journal Landfall (established in 1947), and the bilingual quarterly Te Ao Hou / The New World, which from 1952 to 1975 was a vehicle for Māori writers.

[47] Other members of the Wellington Group included Alistair Te Ariki Campbell and Fleur Adcock; the scholars C. K. Stead and Vincent O'Sullivan also became well-known for their poetry around this time.

[2] Authors like Sturm, Arapera Blank, Rowley Habib and Patricia Grace were published for the first time in Te Ao Hou and became widely known and respected.

[50] Grace was the first Māori woman writer to publish a short story collection (Waiariki) in 1975 and has since received international awards and acclaim for her books for adults and children.

[51] A 1985 article published in the literary journal Landfall by Miriama Evans outlined a lack of publishing of Māori writers with the following being recognised but "largely unpublished": Ani Hona (Te Aniwa Bisch) who received a Literary Fund grant in 1977, Rowley Habib who held the Katherine Mansfield Menton Fellowship in 1984, Bub Bridger who received a grant to attend the First International Feminist Book Fair (London) in 1984, and Bruce Stewart, who received grants from the Queen Elizabeth II Arts Council and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to represent New Zealand at The Association for Commonwealth Literature and Language Studies Conference in Fiji in 1985.

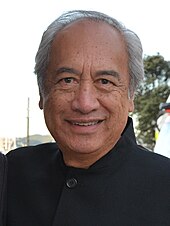

[56][57] Wendt is known for Sons for the Return Home (1973), which describes the experiences of a young Samoan man in New Zealand, and his later novels and short-story collections have formed the foundations for a Pasifika literature in English.

[51] Notable writers in the post-Second World War period include Janet Frame, Owen Marshall, Ronald Hugh Morrieson, Bill Pearson, Sylvia Ashton-Warner and Essie Summers.

[59] The feminist movement in the 1970s and 1980s was the context for many women writers who emerged in that period, including Fiona Kidman, Marilyn Duckworth and Barbara Anderson, who wrote works exploring and challenging gender roles.

[61] Internationally successful New Zealand writers include Elizabeth Knox, known for The Vintner's Luck (1998) and her other diverse fiction, Emily Perkins, Fiona Farrell, Damien Wilkins, Nigel Cox and crime novelist Paul Cleave.

[61] Keri Hulme gained prominence when her novel, The Bone People, won the Booker Prize in 1985; she was the first New Zealander and the first debut novelist to win the prestigious award.

), Janet Frame in the 1980s (To the Is-land, An Angel at my Table and The Envoy from Mirror City), and C. K. Stead's two-part series South-west of Eden (2010) and You Have a Lot to Lose (2020).

In the mid-1980s, aware of the importance of allowing Māori voices to speak, he wrote about what it meant to be a non-Māori New Zealander in Being Pākehā (1985), and published biographies of Frank Sargeson (1995) and Janet Frame (2000).

[69] Recent essay collections by Asian New Zealand writers include All Who Live on Islands (2019) by Rose Lu and Small Bodies of Water (2021) by Nina Mingya Powles.

[72] Other internationally well-known fantasy writers for children and young adults include Sherryl Jordan, Gaelyn Gordon, Elizabeth Knox, Barbara Else and David Hair.

From the 1980s, young adult literature emerged in New Zealand, with authors like Gee, Jack Lasenby, Paula Boock, Kate De Goldi, Fleur Beale, and David Hill tackling serious and controversial topics for teenage readers.

[86] The collective Pacific Underground developed the groundbreaking play Fresh off the Boat (1993), written by Oscar Kightley and Simon Small, which was praised for its portrayal of Samoan life in New Zealand.

[110] The short-lived magazine Phoenix, published in 1932 by students at the University of Auckland and edited by James Munro Bertram and R. A. K. Mason, was an early outlet for New Zealand nationalist writers such as Brasch and Curnow.

[111] Left-wing artist Kennaway Henderson founded the fortnightly magazine Tomorrow in 1934, which was influential in shaping New Zealand nationalist literature and literary criticisms, but was shut down by the government as subversive in 1940.

[114] The magazine New Zealand Listener was founded by the government in 1939 to publish radio listings, but extended its brief to cover current affairs, opinion, and literary works.