Impact crater

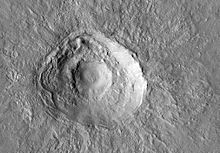

[3] Impact craters are typically circular, though they can be elliptical in shape or even irregular due to events such as landslides.

Where such processes have destroyed most of the original crater topography, the terms impact structure or astrobleme are more commonly used.

[9] Formed in a collision 80 million years ago, the Baptistina family of asteroids is thought to have caused a large spike in the impact rate.

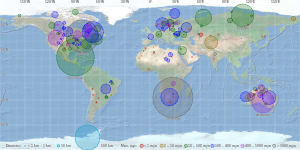

[11] These range in diameter from a few tens of meters up to about 300 km (190 mi), and they range in age from recent times (e.g. the Sikhote-Alin craters in Russia whose creation was witnessed in 1947) to more than two billion years, though most are less than 500 million years old because geological processes tend to obliterate older craters.

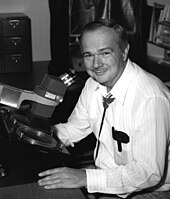

[13]: 41–42 In the 1920s, the American geologist Walter H. Bucher studied a number of sites now recognized as impact craters in the United States.

According to David H. Levy, Shoemaker "saw the craters on the Moon as logical impact sites that were formed not gradually, in eons, but explosively, in seconds."

For his PhD degree at Princeton University (1960), under the guidance of Harry Hammond Hess, Shoemaker studied the impact dynamics of Meteor Crater.

They followed this discovery with the identification of coesite within suevite at Nördlinger Ries, proving its impact origin.

[13] Armed with the knowledge of shock-metamorphic features, Carlyle S. Beals and colleagues at the Dominion Astrophysical Observatory in Victoria, British Columbia, Canada and Wolf von Engelhardt of the University of Tübingen in Germany began a methodical search for impact craters.

Such hyper-velocity impacts produce physical effects such as melting and vaporization that do not occur in familiar sub-sonic collisions.

The fastest impacts occur at about 72 km/s[16] in the "worst case" scenario in which an object in a retrograde near-parabolic orbit hits Earth.

Extremely large bodies (about 100,000 tonnes) are not slowed by the atmosphere at all, and impact with their initial cosmic velocity if no prior disintegration occurs.

Following initial compression, the high-density, over-compressed region rapidly depressurizes, exploding violently, to set in train the sequence of events that produces the impact crater.

Indeed, the energy density of some material involved in the formation of impact craters is many times higher than that generated by high explosives.

[19] It is convenient to divide the impact process conceptually into three distinct stages: (1) initial contact and compression, (2) excavation, (3) modification and collapse.

In practice, there is overlap between the three processes with, for example, the excavation of the crater continuing in some regions while modification and collapse is already underway in others.

Peak pressures in large impacts exceed 1 T Pa to reach values more usually found deep in the interiors of planets, or generated artificially in nuclear explosions.

Stress levels within the shock wave far exceed the strength of solid materials; consequently, both the impactor and the target close to the impact site are irreversibly damaged.

[18] Contact, compression, decompression, and the passage of the shock wave all occur within a few tenths of a second for a large impact.

The subsequent excavation of the crater occurs more slowly, and during this stage the flow of material is largely subsonic.

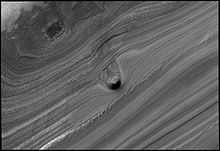

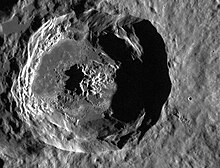

The flow initially produces an approximately hemispherical cavity that continues to grow, eventually producing a paraboloid (bowl-shaped) crater in which the centre has been pushed down, a significant volume of material has been ejected, and a topographically elevated crater rim has been pushed up.

For impacts into highly porous materials, a significant crater volume may also be formed by the permanent compaction of the pore space.

As ejecta escapes from the growing crater, it forms an expanding curtain in the shape of an inverted cone.

Above a certain threshold size, which varies with planetary gravity, the collapse and modification of the transient cavity is much more extensive, and the resulting structure is called a complex crater.

Long after an impact event, a crater may be further modified by erosion, mass wasting processes, viscous relaxation, or erased entirely.

These effects are most prominent on geologically and meteorologically active bodies such as Earth, Titan, Triton, and Io.

Fifty percent of impact structures in North America in hydrocarbon-bearing sedimentary basins contain oil/gas fields.

[41] Large basins, some unnamed but mostly smaller than 300 km, can also be found on Saturn's moons Dione, Rhea and Iapetus.