Impeachment of Andrew Johnson

The Tenure of Office Act had been passed by Congress in March 1867 over Johnson's veto with the primary intent of protecting Stanton from being fired without the Senate's consent.

[1][2] The assassination of Abraham Lincoln on April 14, 1865, just days after the Army of Northern Virginia's surrender at Appomattox, briefly lessened the tension over who would set the terms of peace.

The Radicals, while suspicious of new president Andrew Johnson and his policies, believed based on his record that he would defer or at least acquiesce to their hardline proposals.

Afterward, Johnson denounced Radical Republicans Representative Thaddeus Stevens and Senator Charles Sumner, along with abolitionist Wendell Phillips, as traitors.

[28] Because the Tenure of Office Act did permit the president to suspend such officials when Congress was out of session, after Johnson failed to obtain Stanton's resignation, he instead suspended Stanton on August 5, 1867, which gave him the opportunity to appoint General Ulysses S. Grant, then serving as commanding general of the Army, to serve as the interim secretary of war.

[29] When the Senate adopted a resolution of non-concurrence with Stanton's dismissal in December 1867, Grant told Johnson he was going to resign, fearing punitive legal action.

[34] On February 21, 1868, the president appointed Lorenzo Thomas, a brevet major general in the Army, as secretary of war ad interim.

[36] Johnson's opponents in Congress were outraged by his actions; the president's challenge to congressional authority—with regard to both the Tenure of Office Act and post-war reconstruction—had, in their estimation, been tolerated for long enough.

Expressing the widespread sentiment among House Republicans, Representative William D. Kelley (on February 22, 1868) declared: Sir, the bloody and untilled fields of the ten unreconstructed states, the unsheeted ghosts of the two thousand murdered negroes in Texas, cry, if the dead ever evoke vengeance, for the punishment of Andrew Johnson.

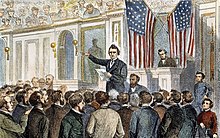

[46][47] The amended resolution read, Resolved, That Andrew Johnson, President of the United States, be impeached of high crimes and misdemeanors in office.

[15] During the debate on the resolution, Republican members of the House Select Committee on Reconstruction argued that Johnson's effort to dismiss Stanton and appoint Thomas ad interim was a specific violation of the Tenure of Office Act.

Ahead of the vote on that previous resolution, Wilson had been tasked by the Judiciary Committee's dissenting members with presenting their argument against impeaching Johnson at that time.

In the closing remarks of formal debate, Stevens expressed his opinion that the case to be brought against Johnson should be broader than just his violation of the Tenure of Office Act.

[50] In the speech, Stevens remarked, This is not to be the temporary triumph of a political party, but is to endure in its consequence until this whole continent shall be filled with a free and untrammeled people or shall be a nest of shrinking, cowardly slaves.

[59] Later that day, George S. Boutwell presented two resolutions to enable the committee of seven that had been appointed to prepare and report the articles of impeachment to sit during sessions of the House.

[60] Thaddeus Stevens felt that Radical Republicans on the committee were yielding too much to moderates to limit the scope of the violations of law that the articles of impeachment would charge Johnson with.

[18] Stevens argued that the articles put before the house had failed to address just how much Johnson had imperiled the governing structure of the United States.

The following day, in hopes of strengthening the case that they would bring before the Senate, the impeachment managers requested that the House consider additional charges.

[18][20][57][75] The first article specifically alleged that Johnson's February 21, 1868, order to remove Stanton was made with intent to violate the Tenure of Office Act.

The second and third articles argued that the appointment of Thomas as secretary of war ad interim was similarly done with intent to violate the Tenure of Office Act.

The eighth article specifically alleged that the appointment of Thomas ad interim was with the intent of unlawfully controlling the property of the Department of War.

The tenth article charged Johnson with attempting, "to bring into disgrace, ridicule, hatred, contempt, and reproach the Congress of the United States", but did not cite a clear violation of the law.

[26][81] The impeachment managers argued that Johnson had explicitly violated the Tenure of Office Act by dismissing Stanton without the consent of the Senate.

One of the points made by the defense was that ambiguity existed in the Tenure of Office Act that left open a vagueness as to whether it was actually applicable to Johnson's firing of Stanton.

They further argued that Johnson was acting in the interest of the necessity of keeping the Department of War functional by appointing Lorenzo Thomas as an interim officer, and that he had caused no public harm in doing so.

During the hiatus, the House passed a resolution to launch an investigation by the impeachment managers of alleged "improper or corrupt means used to influence the determination of the Senate".

In Butler's hearings, and in subsequent inquiries, there was increasing evidence that some acquittal votes were acquired by promises of patronage jobs and cash bribes.

Grimes received assurances that acquittal would not be followed by presidential reprisals; Johnson agreed to enforce the Reconstruction Acts, and to appoint General John Schofield to succeed Stanton.

[93][96][97] In 1887, the Tenure of Office Act was repealed by Congress, and subsequent rulings by the United States Supreme Court seemed to support Johnson's position that he was entitled to fire Stanton without congressional approval.

[99] Lyman Trumbull of Illinois (one of the ten Republican senators whose refusal to vote for conviction prevented Johnson's removal from office) noted in his speech explaining his vote for acquittal, that, had Johnson been convicted, the main source of the American presidency's political power (the freedom for a president to disagree with the Congress without consequences) would have been destroyed, as would Constitution's system of checks and balances.