Slavery in Brazil

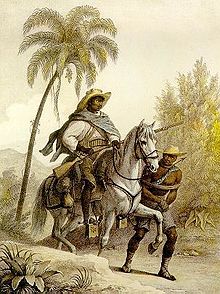

Bandeirantes came from a wide spectrum of backgrounds, including plantation owners, traders, and members of the military, as well as people of mixed ancestry and previously captured Indian slaves.

[13][page needed] Beyond the capture of new slaves and recapture of runaways, bandeiras could also act as large quasi-military forces tasked with exterminating native populations who refused to be subjected to rule by the Portuguese.

As evident through an account of one of Inácio Correia Pamplona's expeditions, bandeirantes liked to think of themselves as brave civilizers who tamed the wildness of frontier by exterminating native populations and providing land for settlers.

[14][page needed] In 1629, Antônio Raposo Tavares led a bandeira, composed of 2,000 allied natives, 900 mamelucos, and 69 whites, to find precious metals and stones and to capture Indians for slavery.

[31] The Confrarias, religious brotherhoods[32][33] that included slaves, both native (Indian) and African, and non-slaves, were frequently a doorway to freedom, as was the "compadrio", co-godparenthood, a part of the kinship network.

"[37][page needed] Jean-Jacques Dessalines was one of the African leaders of the Haitian Revolution that inspired blacks throughout the world to fight for their rights as humans to live and die free.

Masters played a large role in creating tense relations between Africans and Afro-Brazilians, for they generally favored mulattoes and native Brazilian slaves, who consequently experienced better manumission rates.

[38][page needed] Escaped slaves formed maroon[42] communities which played an important role in the histories of other countries such as Suriname, Puerto Rico, Cuba, and Jamaica.

Apart from hostile Native American forces that prevented former slaves from penetrating deeper into Brazil's interior, the main reason for this proximity is that quilombos were usually not economically self-sufficient; relying on raids, theft, and extortion to make ends meet.

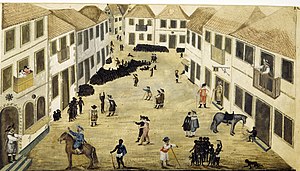

[46] Jean-Baptiste Debret, a French painter who was active in Brazil in the first decades of the 19th century, started out by painting portraits of members of the Brazilian Imperial Family, but soon became concerned with the slavery of both blacks and the indigenous inhabitants.

[50] In colonial Brazil, identity became a complex combination of race, skin color, and socioeconomic status because of the extensive diversity of both the slave and free population.

Anthropologist Jack Goody stated, "Such new names served to cut the individuals off from their kinfolk, their society, from humanity itself and at the same time emphasized their servile status".

Women ex-slaves largely dominated market places selling food and goods in urban areas like Salvador, while a significant percent of African-born men freed from slavery became employed as skilled artisans, including work as sculptors, carpenters, and jewelers.

These differences were heightened after freedom was granted, for lighter skin correlated with social mobility and the greater chance an ex-slave could distance him- or herself from their former slave life.

Labor performed by both slave and freed women was largely divided between domestic work and the market scene, which was much larger in urban cities like Salvador, Recife and Rio de Janeiro.

[51][page needed] Slave owners would buy Mina and Angolan women and girls to work as cooks, household servants, and street vendors or Quitandeiras.

[62][page needed] Slave women were also used by freed men as concubines or common-law wives and often worked for them in addition as household labor, wet nurses, cooks, and peddlers.

[66][page needed] In both small and large estates women were heavily involved in fieldwork, and the chance to be exempted in favor of domestic work was a privilege.

Those couples that were together but unable to marry and living in an informal consensual union were not protected under the church's law and thus could be separated at any point if the owner wanted to sell.

[67] The dual-sphere nature of women's work, in household domestic labor, and in the marketplace, allowed for both additional opportunities at financial resources as well as a larger social circle than their male counterparts.

[51][page needed] Males also did certain kinds of domestic work in cities like Rio, Recife and Salvador, including starching, ironing, fetching water, and dumping waste.

[13][page needed] Gender imbalances were also a key issue in quilmbos, leading, in some cases, to the abduction of black or mulatto women by fugitive slaves.

A national survey conducted in 2000 by the Pastoral Land Commission, a Roman Catholic church group, estimated that there were more than 25,000 forced workers and slaves in Brazil.

[75] A 2017 report by the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy suggested "thousands of workers in Brazil’s meat and poultry sectors were victims of forced labor and inhumane work conditions.

Schools are on holiday, workers have the week off, and a general sense of jubilee fills the streets, where musicians parade around to huge crowds of cheering fans.

Though the media has called it ‘racist’, to a large degree the black-only bloco has become one of the most interesting aspects of Salvador's Carnaval and is continuously accepted as a way of life.

Combined with the influence of Olodum[79] in Salvador, musical protest and representation as a product of slavery and black consciousness has slowly grown into a more powerful force.

Musical representation of problems and issues have long been part of Brazil's history, and Ilê Aiyê and Olodum both produce creative ways to remain relevant and popular.

Capital cities like Rio de Janeiro and even Porto Alegre created permanent markers commemorating heritage sites of slavery and the Atlantic slave trade.

Among the most recent and probably the most famous initiatives of this kind is the Valong Wharf slave memorial in Rio de Janeiro (the site where almost one million enslaved Africans disembarked).