In Athens, on his Banishment

After the assassination of Domitian and accession of Nerva in AD 96, the banishment was cancelled and Dio was allowed to return home.

He mused about whether banishment is difficult for all people or if there are ways of coping with it (2), noting on the one hand that exemplary heroes like Odysseus and Orestes underwent great struggles to escape it (3-6), but on the other hand that the Oracle of Delphi advised Croesus to go into exile voluntarily, which means that the god Apollo must have considered it a fate preferable to death (6-8).

The focus of this section is criticism of the traditional components of an ancient Greek education (paideia), like playing the cithara, wrestling in the gymnasium, learning to read and write, and becoming familiar with classical literature (17-19), instead of what they need to know: ... in order that you will know what is beneficial for yourselves and your country, govern yourselves and live together lawfully and justly with harmony, neither wronging nor plotting against each other...The uselessness of other pursuits is shown by myth: wealth did not rich people, like Atreus, Agamemnon, and Oedipus from misfortune, nor did musical knowledge protect Thamyris, and inventing writing and mathematics did not save Palamedes, either (20-21).

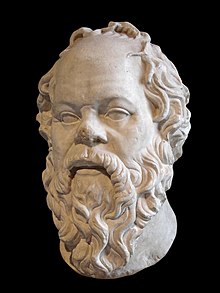

He then launches into the kind of Socratic speech that he used to deliver at Rome (it is unclear how he could have done this while in exile), exorting the Romans to find teachers, whether Roman, Greek, Scythian, or Indian, to teach them self-control (sophrosyne), manly virtue (andreia), and justice (dikaosyne), comparing such a teacher to a doctor for their soul (32-33).

He claims that a focus on virtue instead of luxury would solve Rome's problems with overpopulation, comparing the city to an overladen ship (35).

In gathering wealth, Rome only invites disaster, like Achilles piling treasures on Patroclus' funeral pyre in order to attract the winds and set it alight (36).

Finally, he concludes that the fact that the Romans have already mastered all forms of military knowledge shows that they have the capacity to learn philosophy also.

"[7] John Moles emphasises the "creativity and philosophical expertise of the oration", as well as the way that it "weaves seemingly diverse themes into a complex unity."

[10] Scholars such as Georg Ferdinand Dümmler and Hans von Arnim argued that Dio's discourse and the Clitophon derived from a common source by Antisthenes that is now lost.