Greco-Persian Wars

The collision between the fractious political world of the Greeks and the enormous empire of the Persians began when Cyrus the Great conquered the Greek-inhabited region of Ionia in 547 BC.

Aristagoras secured military support from Athens and Eretria, and in 498 BC these forces helped to capture and burn the Persian regional capital of Sardis.

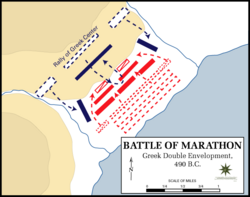

Seeking to secure his empire from further revolts and from the interference of the mainland Greeks, Darius embarked on a scheme to conquer Greece and to punish Athens and Eretria for the burning of Sardis.

The following year, the confederated Greeks went on the offensive, decisively defeating the Persian army at the Battle of Plataea, and ending the invasion of Greece by the Achaemenid Empire.

The actions of the general Pausanias at the siege of Byzantium alienated many of the Greek states from the Spartans, and the anti-Persian alliance was therefore reconstituted around Athenian leadership, called the Delian League.

[5] As historian Tom Holland has it, "For the first time, a chronicler set himself to trace the origins of a conflict not to a past so remote so as to be utterly fabulous, nor to the whims and wishes of some god, nor to a people's claim to manifest destiny, but rather explanations he could verify personally.

[11][12] The richest source for the period, and also the most contemporaneous, is Thucydides' History of the Peloponnesian War, which is generally considered by modern historians to be a reliable primary account.

[13][14][15] Thucydides only mentions this period in a digression on the growth of Athenian power in the run up to the Peloponnesian War, and the account is brief, probably selective and lacks any dates.

In 1939, Greek archaeologist Spyridon Marinatos found the remains of numerous Persian arrowheads at the Kolonos Hill on the field of Thermopylae, which is now generally identified as the site of the defender's last stand.

[24] These cities were Miletus, Myus and Priene in Caria; Ephesus, Colophon, Lebedos, Teos, Clazomenae, Phocaea and Erythrae in Lydia; and the islands of Samos and Chios.

[33] The famous Lydian king Croesus succeeded his father Alyattes in around 560 BC and set about conquering the other Greek city states of Asia Minor.

[56] In 507 BC, Artaphernes, as brother of Darius I and Satrap of Asia Minor in his capital Sardis, received an embassy from newly democratic Athens, probably sent by Cleisthenes, which was looking for Persian assistance to resist the threats from Sparta.

[62][63] The mission was a debacle,[64] and sensing his imminent removal as tyrant, Aristagoras chose to incite the whole of Ionia into rebellion against the Persian king Darius the Great.

The Persians responded in 497 BC with a three-pronged attack aimed at recapturing the outlying areas of the rebellious territory,[67] but the spread of the revolt to Caria meant the largest army, under Darius, moved there instead.

[74] The Persians spent 493 BC reducing the cities along the west coast that still held out against them,[75] before finally imposing a peace settlement on Ionia that was considered[by whom?]

Xerxes decided that the Hellespont would be bridged to allow his army to cross to Europe, and that a canal should be dug across the isthmus of Mount Athos (a Persian fleet had been destroyed in 492 BC while rounding this coastline).

[131] Having crossed into Europe in April 480 BC, the Persian army began its march to Greece, taking 3 months to travel unopposed from the Hellespont to Therme.

However, towards the end of the second day, they were betrayed by a local resident named Ephialtes who revealed to Xerxes a mountain path that led behind the Allied lines, according to Herodotus.

[144] The Peloponnesian Allies began to prepare a defensive line across the Isthmus of Corinth, building a wall, and demolishing the road from Megara, abandoning Athens to the Persians.

[152] Seizing the opportunity, the Allied fleet attacked, and scored a decisive victory, sinking or capturing at least 200 Persian ships, therefore ensuring the safety of the Peloponnessus.

[154] His general Mardonius volunteered to remain in Greece and complete the conquest with a hand-picked group of troops, while Xerxes retreated to Asia with the bulk of the army.

In particular, the Athenians, who were not protected by the Isthmus, but whose fleet was the key to the security of the Peloponnesus, felt that they had been treated unfairly, and so they refused to join the Allied navy in the spring.

[169] While many modern historians doubt that Mycale took place on the same day as Plataea, the battle may well only have occurred once the Allies received news of the events unfolding in Greece.

[182] Control of both Sestos and Byzantium gave the allies command of the straits between Europe and Asia (over which the Persians had crossed), and allowed them access to the merchant trade of the Black Sea.

[187] In the aftermath of Mycale, the Spartan king Leotychides had proposed transplanting all the Greeks from Asia Minor to Europe as the only method of permanently freeing them from Persian dominion.

[188] Throughout the 470s BC, the Delian League campaigned in Thrace and the Aegean to remove the remaining Persian garrisons from the region, primarily under the command of the Athenian politician Cimon.

Plutarch suggests that in the aftermath of the victory at the Eurymedon, Artaxerxes had agreed to a peace treaty with the Greeks, even naming Callias as the Athenian ambassador involved.

[19] This embassy may have been an attempt to reach some kind of peace agreement, and it has even been suggested that the failure of these hypothetical negotiations led to the Athenian decision to support the Egyptian revolt.

A further argument for the existence of the treaty is the sudden withdrawal of the Athenians from Cyprus in 449 BC, which Fine suggests makes most sense in the light of some kind of peace agreement.

Furthermore, Athens had already demonstrated their superiority at sea at the Eurymedon and Salamis-in-Cyprus, so any legal limitations for the Persian fleet were nothing more than "de jure" recognition of military realities.