Inclusion–exclusion principle

The formula expresses the fact that the sum of the sizes of the two sets may be too large since some elements may be counted twice.

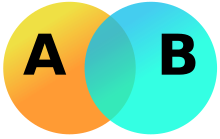

The inclusion-exclusion principle, being a generalization of the two-set case, is perhaps more clearly seen in the case of three sets, which for the sets A, B and C is given by This formula can be verified by counting how many times each region in the Venn diagram figure is included in the right-hand side of the formula.

To find the cardinality of the union of n sets: The name comes from the idea that the principle is based on over-generous inclusion, followed by compensating exclusion.

[3] Sometimes the principle is referred to as the formula of Da Silva or Sylvester, due to these publications.

[5] This inverse has a special structure, making the principle an extremely valuable technique in combinatorics and related areas of mathematics.

denote the complement of Ai in S, by De Morgan's laws we have As another variant of the statement, let P1, ..., Pn be a list of properties that elements of a set S may or may not have, then the principle of inclusion–exclusion provides a way to calculate the number of elements of S that have none of the properties.

Just let Ai be the subset of elements of S which have the property Pi and use the principle in its complementary form.

[1] Notice that if you take into account only the first m to be the total number of permutations, the probability Q that a random shuffle produces a derangement is given by a truncation to n + 1 terms of the Taylor expansion of e−1. The situation that appears in the derangement example above occurs often enough to merit special attention. A generalization of this concept would calculate the number of elements of S which appear in exactly some fixed m of these sets. , the inclusion–exclusion principle becomes for n = 2 for n = 3 and in general which can be written in closed form as where the last sum runs over all subsets I of the indices 1, ..., n which contain exactly k elements, and denotes the intersection of all those Ai with index in I. If, in the probabilistic version of the inclusion–exclusion principle, the probability of the intersection AI only depends on the cardinality of I, meaning that for every k in {1, ..., n} there is an ak such that then the above formula simplifies to due to the combinatorial interpretation of the binomial coefficient , in which case the expression above simplifies to (This result can also be derived more simply by considering the intersection of the complements of the events as a set of its prime factors, then (2) is a generalization of Möbius inversion formula for square-free natural numbers. Therefore, (2) is seen as the Möbius inversion formula for the incidence algebra of the partially ordered set of all subsets of A. A well-known application of the inclusion–exclusion principle is to the combinatorial problem of counting all derangements of a finite set. / e] where [x] denotes the nearest integer to x; a detailed proof is available here and also see the examples section above. The first occurrence of the problem of counting the number of derangements is in an early book on games of chance: Essai d'analyse sur les jeux de hazard by P. R. de Montmort (1678 – 1719) and was known as either "Montmort's problem" or by the name he gave it, "problème des rencontres. The principle of inclusion–exclusion, combined with De Morgan's law, can be used to count the cardinality of the intersection of sets as well. By letting Ai be the set of positions that the element i is not allowed to be in, and the property Pi to be the property that a permutation puts element i into a position in Ai, the principle of inclusion–exclusion can be used to count the number of permutations which satisfy all the restrictions. Using the universal set consisting of all partitions of the n-set into k (possibly empty) distinguishable boxes, A1, A2, ..., Ak, and the properties Pi meaning that the partition has box Ai empty, the principle of inclusion–exclusion gives an answer for the related result. The number of ways to place n non-attacking rooks on the complete n × m "checkerboard" (without regard as to whether the rooks are placed in the squares of the board B) is given by the falling factorial: Letting Pi be the property that an assignment of n non-attacking rooks on the complete board has a rook in column i which is not in a square of the board B, then by the principle of inclusion–exclusion we have:[17] Euler's totient or phi function, φ(n) is an arithmetic function that counts the number of positive integers less than or equal to n that are relatively prime to n. That is, if n is a positive integer, then φ(n) is the number of integers k in the range 1 ≤ k ≤ n which have no common factor with n other than 1. Let S be the set {1, ..., n} and define the property Pi to be that a number in S is divisible by the prime number pi, for 1 ≤ i ≤ r, where the prime factorization of Then,[18] The Dirichlet hyperbola method re-expresses a sum of a multiplicative function , splitting this region into two overlapping subregions, and finally using the inclusion–exclusion principle to conclude that In many cases where the principle could give an exact formula (in particular, counting prime numbers using the sieve of Eratosthenes), the formula arising does not offer useful content because the number of terms in it is excessive. If each term individually can be estimated accurately, the accumulation of errors may imply that the inclusion–exclusion formula is not directly applicable. After a slow start, his ideas were taken up by others, and a large variety of sieve methods developed. These for example may try to find upper bounds for the "sieved" sets, rather than an exact formula. Let A1, ..., An be arbitrary sets and p1, ..., pn real numbers in the closed unit interval [0, 1]. Then, for every even number k in {0, ..., n}, the indicator functions satisfy the inequality:[19] Choose an element contained in the union of all sets and let