Economy of Denmark

Denmark is a modern high-income and highly developed mixed economy, dominated by the service sector with 80% of all jobs; about 11% of employees work in manufacturing and 2% in agriculture.

[31] Though eligible to join the EU's Economic and Monetary Union (EMU), Danish voters in a referendum in 2000 rejected exchanging the krone for the euro.

In an international context, a relatively large proportion of the population is part of the labour force, in particular because the female participation rate is very high.

The material standard of living has experienced formerly unknown rates of growth, and the country has been industrialized and later turned into a modern service society.

The emerging trade implied specialization which created demand for means of payments, and the earliest known Danish coins date from the time of Svend Tveskæg around 995.

[35] Improvements in shipping technology allowed traders to sail around Jutland and into the Baltic Sea directly, and Danish warships collected the Sound Toll from these mainly Dutch merchants, in exchange for protection.

Nordic rulers before the mid-seventeenth century welcomed the Dutch merchants for their efficient shipping services and inflow of investments which boosted industrial development.

There exists national accounting data for Denmark from 1820 onwards thanks to the pioneering work of Danish economic historian Svend Aage Hansen.

For the next decades the Danish economy struggled with several major so-called "balance problems": High unemployment, current account deficits, inflation, and government debt.

[44] A series of tax reforms from 1987 onwards, reducing tax deductions on interest payments, and the increasing importance of compulsory labour market-based funded pensions from the 1990s have increased private savings rates considerably, consequently transforming secular current account deficits to secular surpluses.

[45] Instead, issues like decreasing productivity growth rates and increasing inequality in income distribution and consumption possibilities are prevalent in the public debate.

The global Great Recession during the late 2000s, the accompanying Euro area debt crisis and their repercussions marked the Danish economy for several years.

Until 2017, unemployment rates have generally been considered to be above their structural level, implying a relatively stagnating economy from a business-cycle point of view.

As of August 2023[update] Novo Nordisk's market capitalization—Europe's second-largest, after LVMH—exceeded the size of the entire national economy, and it is the largest payer of corporate taxes to the Danish state.

Some worried that the nation might become overdependent on the company, similar to what happened to the economy of Finland with Nokia, or that Novo Nordisk's success might cause Dutch disease.

A large part of the pension wealth is invested abroad, thus giving rise to a fair amount of foreign capital income.

Denmark first introduced active labour market policies (ALMPs) in the 1990s after an economic recession that resulted in high unemployment rates.

For instance, the Building Bridge to Education program was started in 2014 to provide mentors and skill development classes to youth that are at risk of unemployment.

[71] Denmark has a very long tradition of maintaining a fixed exchange-rate system, dating back to the period of the gold standard during the time of the Scandinavian Monetary Union from 1873 to 1914.

After the breakdown of the international Bretton Woods system in 1971, Denmark devalued the krone repeatedly during the 1970s and the start of the 1980s, effectively maintaining a policy of "fixed, but adjustable" exchange rates.

Consequently, the Danish krone is the only currency in the European Exchange Rate Mechanism II (ERM II),[74] before Bulgaria and Croatia joined in 2020 (the latter uses the euro since 2023)[75] In the first months of 2015, Denmark experienced the largest pressure against the fixed exchange rate for many years because of very large capital inflows, causing a tendency for the Danish krone to appreciate.

(e.g. a likely ageing of the population caused by a considerable expansion of life expectancy), consider the Danish fiscal policy to be overly sustainable in the long run.

[85][86] This implies that under the assumptions employed in the projections, fiscal policy could be permanently loosened (via more generous public expenditures and/or lower taxes) by c. 1% of GDP while still maintaining a stable government debt-to-GDP ratio in the long run.

Denmark has a countrywide, but municipally administered social support system against poverty, securing that qualified citizens have a minimum living income.

[102] The Danish agricultural industry is historically characterized by freehold and family ownership, but due to structural development farms have become fewer and larger.

[110] Denmark houses a number of significant engineering and high-technology firms, within the sectors of industrial equipment, aerospace, robotics, pharmaceutical and electronics.

Danfoss, headquartered in Nordborg, designs and manufactures industrial electronics, heating and cooling equipment, as well as drivetrains and power solutions.

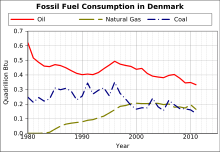

[117] The course took a giant leap forward in 1984, when the Danish North Sea oil and gas fields, developed by native industry in close cooperation with the state, started major productions.

[124] The so-called "green taxes" have been broadly criticised partly for being higher than in other countries, but also for being more of a tool for gathering government revenue than a method of promoting "greener" behaviour.

Notable companies dedicated to the pharmaceutical and biotechnology sector, includes: Denmark has a long tradition for cooperative production and trade on a large scale.