Independent equation

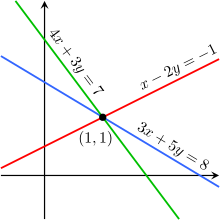

[1] The concept typically arises in the context of linear equations.

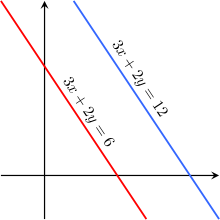

In contrast, if an equation is dependent on the others, then it provides no information not contained in the others collectively, and the equation can be dropped from the system without any information loss.

The number of independent equations in a system of consistent equations (a system that has at least one solution) can never be greater than the number of unknowns.

Equivalently, if a system has more independent equations than unknowns, it is inconsistent and has no solutions.

The concepts of dependence and independence of systems are partially generalized in numerical linear algebra by the condition number, which (roughly) measures how close a system of equations is to being dependent (a condition number of infinity is a dependent system, and a system of orthogonal equations is maximally independent and has a condition number close to 1.)