Indian Territory in the American Civil War

As part of the Trans-Mississippi Theater, the Indian Territory was the scene of numerous skirmishes and seven officially recognized battles[1] involving both Native American units allied with the Confederate States of America and Native Americans loyal to the United States government, as well as other Union and Confederate troops.

[2] A total of at least 7,860 Native Americans from the Indian Territory participated in the Confederate Army, as both officers and enlisted men;[3] most came from the Five Civilized Tribes: the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole nations.

[6] Leaders from each of the Five Civilized Tribes, acting without the consensus of their councils, agreed to be annexed by the Confederacy in exchange for certain rights, including protection and recognition of current tribal lands.

[7] After reaching Kansas and Missouri, Opothleyahola and Native Americans loyal to the Union formed three volunteer regiments known as the Indian Home Guard.

[8][9] The following Indian Nations not only had suffered forced migration at the hands of the American government but signed treaties of alliance with the CSA: After abandoning its forts in the Indian Territory early in the Civil War, the Union Army was unprepared for the logistical challenges of trying to regain control of the territory from the Confederate government.

A force of 1,400 Confederate soldiers under Colonel Douglas H. Cooper initiated the Battle of Round Mountain, but were repulsed after several waves, leading to a Southern defeat.

In 1862, Union General James G. Blunt ordered Colonel William Weer to lead an expedition into the Indian Territory.

[12] Weer's expedition departed from Baxter Springs, Kansas and met with early success at the Battle of Locust Grove in Indian Territory on July 3.

In the First Battle of Cabin Creek, which occurred July 1–2, 1863, the Union escort was led by Colonel James Monroe Williams.

Williams was alerted to the attack and, despite the waters of the creek being swelled by rain, made a successful counterattack upon the entrenched Confederate position and forced them to flee.

[17] Honey Springs Depot, a site of frequent skirmishes, was chosen by General James G. Blunt as the place to engage the largest Confederate forces in Indian Territory.

On the morning of July 17, he engaged Cooper in the Battle of Honey Springs, who commanded a force of 3,000–6,000 men composed primarily of Native Americans.

General Blunt, who had returned to Fort Gibson, learned that the Confederates had regrouped there and believed his troops could capture the depot and destroy Cooper's forces.

[20] Instead of following the retreating Confederates southwest toward Boggy Depot, Blunt proceeded to attack Fort Smith, which he captured on September 1, 1863.

[e] Armed gangs known as "free raiders" mostly stole horses and cattle, while burning the communities of both Confederate and Indian supporters.

Watie also targeted military supply trains because that not only deprived the Union troops of food, forage and ammunition but gave significant amounts of other booty that he could distribute to his men.

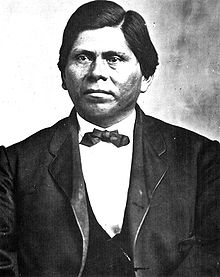

Watie went to Washington, D.C. later that year for negotiations on behalf of his tribe; as the principal chief of the pro-Confederacy group elected in 1862, he was seeking recognition of a Southern Cherokee Nation.