Indian rope trick

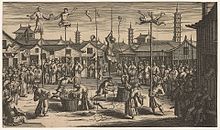

Sometimes described as "the world’s greatest illusion", it reputedly involved a magician, a length of rope, and one or more boy assistants.

"[4] In his commentary on Gaudapada's explanation of the Mandukya Upanishad, the 9th-century Hindu teacher Adi Shankara, illustrating a philosophical point, wrote of a juggler who throws a thread up into the sky; he climbs up it carrying weapons and goes out of sight; he engages in a battle in which he is cut into pieces, which fall down; finally he arises again.

Finally the basket was upturned, the body pieces fell out topsy turvy, and Melton "saw all those limbs creep together again," the man being restored to life.

The magician's son climbs the rope, vanishes from sight, and then (supposedly) tosses down a peach, before being "caught by the Garden's guards" and "killed", with his dismembered body falling from above in the traditional manner.

[18] In 1917, Lieutenant Frederick William Holmes stated that whilst on his veranda with a group of officers in Kirkee, he had observed the trick being performed by an old man and young boy.

"[21] Holmes later admitted this, but the photograph was reproduced by the press in several magazines and newspapers as proof of the trick having been successfully demonstrated.

[21][22] In 1919, G. Huddleston, writing in Nature, claimed to have spent more than thirty years in India and known many of the best conjurors in the country, but not one of them could demonstrate the trick.

[26] Magicians such as Harry Blackstone Sr., David Devant, Horace Goldin, Carl Hertz, Servais Le Roy and Howard Thurston incorporated the Indian rope trick into their stage shows.

The real challenge was to perform the full trick including the disappearance of the boy in broad daylight, outside in the open air.

"[29] In 1934 the Occult Committee of The Magic Circle, convinced the trick did not exist, offered a large reward to anyone who could perform it in the open air.

The American magician Robert Heger claimed to have perfected the trick over 20 years and would demonstrate it to an audience on stage in Saint Paul, Minnesota.

[36] In 1935, Karachi sent a challenge to the skeptics, for 200 guineas to be deposited with a neutral party who would decide if the rope trick was performed satisfactorily.

The place could be any open area chosen by the neutral party and agreed to by the conjurers, and the spectators could be anywhere in front of the carpet on which Karachi would be seated.

Citing their work, historian Mike Dash wrote in 2000: Ranking their cases in order of impressiveness, Wiseman and Lamont discovered that the average lapse of time between the event and witness's report of the event was a mere four years in the least notable examples, but a remarkable forty-one years in the case of the most complex and striking accounts.

One answer would be that they already knew, or subsequently discovered, how the full-blown Indian rope trick was supposed to look, and drew on this knowledge when embroidering their accounts.

"[43] In his book on the topic, Peter Lamont claimed the story of the trick resulted from a hoax created by John Elbert Wilkie while working at the Chicago Tribune.

A diminutive boy, not much larger than an Indian monkey, climbed up to the top of the pole and was out of sight of the audience unless they bent forward and looked beneath the awning, when the sun shone in their eyes and blinded them.

He translated an article by the German magician Erik Jan Hanussen who claimed to have observed the secret to the trick in a village near Babylon.

According to Hanussen the spectators were positioned in front of a blazing sun and the "rope" was actually made from the vertebrae of a sheep covered with sailing cord that was twisted into a solid pole.

[50] Analyzing old eyewitness reports, Jim McKeague explained how poor, itinerant conjuring troupes could have performed the trick using known magical techniques.

As it unwinds completely the illusion of the ball disappearing into the sky is striking, especially if the pale cord is similar in color to any overcast cloud.

[52] The lifter continues to look upwards and holds a conversation with the "climber" using ventriloquism to create the illusion that a person is still high in the air and is just passing out of sight.

[53] As to the falling of the pieces of the climber, according to an Indian barrister-at-law who saw a performance about 1875 which included this feature, it appears to have been produced very largely by acting and sound effects.

[54] When a magician acts out the visible catch of an imaginary deck of cards thrown by a spectator, or throws a ball in the air where it vanishes, the appearance or disappearance really occurs at the location of the magician's hand, but to most spectators (two out of three in actual testing[55]) the magic appears to occur in mid-air.

A horizontal wire is stretched above the site, anchored at ground points of higher elevation, rather than obvious nearby structures.

Keel describes his public attempt to perform a simpler version, but failing badly, according to "two articles and a cartoon that appeared in Indian newspapers".

As they walked back, an assistant ran up and claimed the fakir was in the midst of the trick, so they rushed the rest of the way so they wouldn't miss it.

A sheet was then removed from a boy with fake blood at his neck and shoulders, hinting that his limbs and head had been reattached to his torso.