Indonesian National Revolution

Budi Utomo, Sarekat Islam and others pursued strategies of co-operation by joining the Dutch initiated Volksraad ("People's Council") in the hope that Indonesia would be granted self-rule.

[citation needed] The occupation of Indonesia by Japan for three and a half years during World War II was a crucial factor in the subsequent revolution.

(translation by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, October 1948)[33]It was mid-September before news of the declaration of independence spread to the outer islands, and many Indonesians far from the capital Jakarta did not believe it.

[38] By September 1945, control of major infrastructure installations, including railway stations and trams in Java's largest cities, had been taken over by Republican pemuda who encountered little Japanese resistance.

[39] Republican newspapers and journals were common in Jakarta, Yogyakarta, and Surakarta, which fostered a generation of writers known as angkatan 45 ('generation of 45') many of whom believed their work could be part of the revolution.

[40] Pro-revolution demonstrations took place in large cities, including one in Jakarta on 19 September with over 200,000 people, which Sukarno and Hatta, fearing violence, successfully quelled.

It was common for ethnic 'out-groups' – Dutch internees, Eurasian, Ambonese and Chinese – and anyone considered to be a spy, to be subjected to intimidation, kidnapping, robbery, murder and organised massacres.

[29] The Dutch East Indies administration had just received a ten million dollar loan from the United States to finance its return to Indonesia.

Allied enclaves already existed in Kalimantan (Indonesian Borneo), Morotai (Maluku) and parts of Irian Jaya; Dutch administrators had already returned to these areas.

[41] The first stages of warfare were initiated in October 1945 when, in accordance with the terms of their surrender, the Japanese tried to re-establish the authority they had relinquished to Indonesians in the towns and cities.

[41][57] Republican attacks against Allied and alleged pro-Dutch civilians reached a peak in November and December, with 1,200 killed in Bandung as the pemuda returned to the offensive.

Although the European forces largely captured the city in three days, the poorly armed Republicans fought on until 29 November[65] and thousands died as the population fled to the countryside.

[citation needed] With British assistance, the Dutch landed their Netherlands Indies Civil Administration (NICA) forces in Jakarta and other key centres.

In December 1946, Special Forces Depot (DST), led by commando and counter-insurgency expert Captain Raymond "Turk" Westerling, were accused of pacifying the southern Sulawesi region using arbitrary terror techniques, which were copied by other anti-Republicans.

[68] The Linggadjati Agreement, brokered by the British and concluded in November 1946, saw the Netherlands recognise the Republic as the de facto authority over Java, Madura, and Sumatra.

The Republican-controlled Java and Sumatra would be one of its states, alongside areas that were generally under stronger Dutch influence, including southern Kalimantan, and the "Great East", which consisted of Sulawesi, Maluku, the Lesser Sunda Islands, and Western New Guinea.

The whole situation deteriorated to such an extent that the Dutch Government was obliged to decide that no progress could be made before law and order were restored sufficiently to make intercourse between the different parts of Indonesia possible, and to guarantee the safety of people of different political opinions.

[73] Indonesian Republic faced economic hardship due to continued naval blockade and land blockades at Renville line (in violation of Renville Agreement)[76][77][73] which affect sufficient availability of not only arms, but also food, clothing,[77] medicines including bandages, mails, books, magazines,[78] material to service and repair transportation,[79] and overpopulation because of people fleeing from Dutch advances in Operation Product.

The fear of such incursions actually succeeding, along with apparent Republican undermining of the Dutch-established Pasundan state[citation needed] and negative reports, led to the Dutch leadership increasingly seeing itself as losing control.

[85] The Republican president, vice-president, and all but six Republic of Indonesia ministers were captured by Dutch troops and exiled on Bangka Island off the east coast of Sumatra.

[citation needed] Although Dutch forces conquered the towns and cities in Republican heartlands on Java and Sumatra, they could not control villages and the countryside.

[91] The so-called 'social revolutions' following the independence proclamation were challenges to the Dutch-established Indonesian social order, and to some extent a result of the resentment against Japanese-imposed policies.

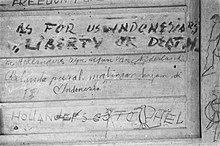

"We are free" The resilience of Indonesian Republican resistance and active international diplomacy set world opinion against the Dutch efforts to re-establish their colony.

[citation needed] Republican-controlled Java and Sumatra together formed a single state in the seven-state, nine-territory RUSI federation, but accounted for almost half its population.

On 25 April 1950, an independent Republic of South Maluku (RMS) was proclaimed in Ambon but this was suppressed by Republican troops during a campaign from July to November.

Van der Eng states that conflict led to significant ramifications for Indonesians outside of direct violence, such as widespread famine, disease and a lowered fertility rate.

The Republic had to set up all necessities of life, ranging from 'postage stamps, army badges, and train tickets' whilst subject to Dutch trade blockades.

Despite their ill-discipline raising the prospect of anarchy, without pemuda confronting foreign and Indonesian colonial forces, Republican diplomatic efforts would have been futile.

It did not, however, significantly improve the economic or political fortune of the population's poverty-stricken peasant majority; only a few Indonesians were able to gain a larger role in commerce, and hopes for democracy were dashed within a decade.

According to the review, "The use of extreme violence by the Dutch armed forces was not only widespread, but often deliberate, too" and "was condoned at every level: political, military and legal."