Indus script

Most inscriptions containing these symbols are extremely short, making it difficult to judge whether or not they constituted a writing system used to record a Harappan language, any of which are yet to be identified.

[7] By 1992, an estimated 4,000 inscribed objects had been discovered,[8] some as far afield as Mesopotamia due to existing Indus–Mesopotamia relations, with over 400 distinct signs represented across known inscriptions.

[16][17] Linguists such as Iravatham Mahadevan, Kamil Zvelebil, and Asko Parpola have argued that the script had a relation to a Dravidian language.

[21] Indus script symbols have primarily been found on stamp seals, pottery, bronze, and copper plates, tools, and weapons.

[24] No extant examples of the Indus script have been found on perishable organic materials like papyrus, paper, textiles, leaves, wood, or bark.

[25] However, excavations at Harappa have demonstrated the development of some symbols from potter's marks and graffiti belonging to the earlier Ravi phase from c. 3500–2800 BCE.

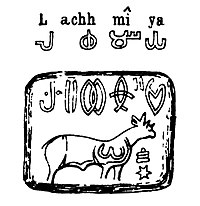

[1][2] In the Mature Harappan period, from about c. 2600–1900 BCE, strings of Indus signs are commonly found on flat, rectangular stamp seals as well as written or inscribed on a multitude of other objects including pottery, tools, tablets, and ornaments.

Signs were written using a variety of methods including carving, chiselling, embossing, and painting applied to diverse materials such as terracotta, sandstone, soapstone, bone, shell, copper, silver, and gold.

[31] Both seals and potsherds bearing Indus script text, dated c. 2200–1600 BCE, have been found at sites associated with the Daimabad culture of the Late Harappan period, in present-day Maharashtra.

Some scholars, such as the anthropologist Gregory Possehl,[4] have argued that the non-Brahmi graffiti symbols are a survival and development of the Indus script into and during the 1st millennium BCE.

[45][5] In the 1970s, the Indian epigrapher Iravatham Mahadevan published a corpus and concordance of Indus inscriptions listing 419 distinct signs in specific patterns.

[49][51] Although the script is undeciphered, the writing direction has been deduced from external evidence, such as instances of the symbols being compressed on the left side as if the writer is running out of space at the end of the row.

[51] Some researchers have sought to establish a relationship between the Indus script and Brahmi, arguing that it is a substratum or ancestor to later writing systems used in the region of the Indian subcontinent.

[54] However, researchers now generally agree that the Indus script is not closely related to any other writing systems of the second and third millennia BCE, although some convergence or diffusion with Proto-Elamite conceivably may be found.

These similarities were first suggested by early European scholars, such as the archaeologist John Marshall[57] and the Assyriologist Stephen Langdon,[58] with some, such as G. R. Hunter,[10] proposing an indigenous origin of Brahmi with a derivation from the Indus script.

[k] In 2025, Tamil Nadu Chief Minister M. K. Stalin announced a $1 million (USD) prize for deciphering the Indus Valley Script, stating that "Archaeologists, Tamil computer software experts and computer experts across the world have been making efforts to decipher the script but it remains a mystery even after 100 years.

"[72] Although no clear consensus has been established, there are those who argue that the Indus script recorded an early form of the Dravidian languages (Proto-Dravidian).

[75] Supporting this work, the archaeologist Walter Fairservis argued that Indus script text on seals could be read as names, titles, or occupations, and suggested that the animals depicted were totems indicating kinship or possibly clans.

[93] An opposing hypothesis is that these symbols are nonlinguistic signs which symbolise families, clans, gods, and religious concepts, and are similar to components of coats of arms or totem poles.

In a 2004 article, Steve Farmer, Richard Sproat, and Michael Witzel presented a number of arguments stating that the Indus script is nonlinguistic.

A 2009 paper[80] published by Rajesh P. N. Rao, Iravatham Mahadevan, and others in the journal Science also challenged the argument that the Indus script might have been a nonlinguistic symbol system.

[106] The font was developed based on a corpus compiled by Indologist Asko Parpola in his book Deciphering the Indus Script.