Brahmi script

[27] The underlying system of numeration, however, was older, as the earliest attested orally transmitted example dates to the middle of the 3rd century CE in a Sanskrit prose adaptation of a lost Greek work on astrology.

The Lalitavistara Sūtra states that young Siddhartha, the future Gautama Buddha (~500 BCE), mastered philology, Brahmi and other scripts from the Brahmin Lipikāra and Deva Vidyāsiṃha at a school.

This is accepted by the vast majority of script scholars since the publications by Albrecht Weber (1856) and Georg Bühler's On the origin of the Indian Brahma alphabet (1895).

Some authors – both Western and Indian – suggest that Brahmi was borrowed or inspired by a Semitic script, invented in a short few years during the reign of Ashoka, and then used widely for Ashokan inscriptions.

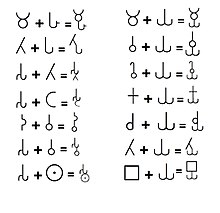

[49] Justeson and Stephens proposed that this inherent vowel system in Brahmi and Kharoṣṭhī developed by transmission of a Semitic abjad through the recitation of its letter values.

He tended to place much weight on phonetic congruence as a guideline, for example connecting c to tsade 𐤑 rather than kaph 𐤊, as preferred by many of his predecessors.

Bühler cited a near-modern practice of writing Brahmic scripts informally without vowel diacritics as a possible continuation of this earlier abjad-like stage in development.

[75] Further, adds Salomon, in a "limited sense Brahmi can be said to be derived from Kharosthi, but in terms of the actual forms of the characters, the differences between the two Indian scripts are much greater than the similarities".

[82] British archaeologist Raymond Allchin stated that there is a powerful argument against the idea that the Brahmi script has Semitic borrowing because the whole structure and conception is quite different.

[84] Today the indigenous origin hypothesis is more commonly promoted by non-specialists, such as the computer scientist Subhash Kak, the spiritual teachers David Frawley and Georg Feuerstein, and the social anthropologist Jack Goody.

[99][100][101][full citation needed] Scharfe adds that the best evidence is that no script was used or ever known in India, aside from the Persian-dominated Northwest where Aramaic was used, before around 300 BCE because Indian tradition "at every occasion stresses the orality of the cultural and literary heritage",[66] yet Scharfe in the same book admits that "a script has been discovered in the excavations of the Indus Valley Civilization that flourished in the Indus valley and adjacent areas in the third millennium B.C.

"[102] Megasthenes, a Greek ambassador to the Mauryan court in Northeastern India only a quarter century before Ashoka, noted "... and this among a people who have no written laws, who are ignorant even of writing, and regulate everything by memory.

[104] Timmer considers it to reflect a misunderstanding that the Mauryans were illiterate "based upon the fact that Megasthenes rightly observed that the laws were unwritten and that oral tradition played such an important part in India.

Kenneth Norman (2005) suggests that Brahmi was devised over a longer period of time predating Ashoka's rule:[110] Support for this idea of pre-Ashokan development has been given very recently by the discovery of sherds at Anuradhapura in Sri Lanka, inscribed with small numbers of characters which seem to be Brāhmī.

[112] Jack Goody (1987) had similarly suggested that ancient India likely had a "very old culture of writing" along with its oral tradition of composing and transmitting knowledge, because the Vedic literature is too vast, consistent and complex to have been entirely created, memorized, accurately preserved and spread without a written system.

While Falk (1993) disagrees with Goody,[115] while Walter Ong and John Hartley (2012) concur,[116] not so much based on the difficulty of orally preserving the Vedic hymns, but on the basis that it is highly unlikely that Panini's grammar was composed.

[118] Later Chinese Buddhist account of the 6th century CE also supports its creation to the god Brahma, though Monier Monier-Williams, Sylvain Lévi and others thought it was more likely to have been given the name because it was moulded by the Brahmins.

[119][120] Alternatively, some Buddhist sutras such as the Lalitavistara Sūtra (possibly 4th century CE), list Brāhmī and Kharoṣṭī as some of the sixty-four scripts the Buddha knew as a child.

[128][129] Surviving ancient records of the Brahmi script are found as engravings on pillars, temple walls, metal plates, terracotta, coins, crystals and manuscripts.

The historical sequence of the specimens was interpreted to indicate an evolution in the level of stylistic refinement over several centuries, and they concluded that the Brahmi script may have arisen out of "mercantile involvement" and that the growth of trade networks in Sri Lanka was correlated with its first appearance in the area.

[131] Indologist Harry Falk has argued that the Edicts of Ashoka represent an older stage of Brahmi, whereas certain paleographic features of even the earliest Anuradhapura inscriptions are likely to be later, and so these potsherds may date from after 250 BCE.

[133] More recently in 2013, Rajan and Yatheeskumar published excavations at Porunthal and Kodumanal in Tamil Nadu, where numerous both Tamil-Brahmi and "Prakrit-Brahmi" inscriptions and fragments have been found.

[142] James Prinsep, an archaeologist, philologist, and official of the East India Company, started to analyse the inscriptions and made deductions on the general characteristics of the early Brahmi script essentially relying on statistical methods.

[155][156][157][158] In a series of results that he published in March 1838 Prinsep was able to translate the inscriptions on a large number of rock edicts found around India, and provide, according to Richard Salomon, a "virtually perfect" rendering of the full Brahmi alphabet.

[161][162] In English, the most widely available set of reproductions of Brahmi texts found in Sri Lanka is Epigraphia Zeylanica; in volume 1 (1976), many of the inscriptions are dated to the 3rd–2nd century BCE.

[165][166] According to Frederick Asher, Tamil Brahmi inscriptions on potsherds have been found in Quseir al-Qadim and in Berenike, Egypt, which suggest that merchant and trade activity was flourishing in ancient times between India and the Red Sea region.

Early "Ashokan" Brahmi (3rd–1st century BCE) is regular and geometric, and organized in a very rational fashion: The final letter does not fit into the table above; it is 𑀴 ḷa.

[182] 𑀤𑁂𑀯𑀸𑀦𑀁𑀧𑀺𑀬𑁂𑀦 𑀧𑀺𑀬𑀤𑀲𑀺𑀦 𑀮𑀸𑀚𑀺𑀦𑀯𑀻𑀲𑀢𑀺𑀯𑀲𑀸𑀪𑀺𑀲𑀺𑀢𑁂𑀦 Devānaṃpiyena Piyadasina lājina vīsati-vasābhisitena 𑀅𑀢𑀦𑀆𑀕𑀸𑀘 𑀫𑀳𑀻𑀬𑀺𑀢𑁂 𑀳𑀺𑀤𑀩𑀼𑀥𑁂𑀚𑀸𑀢 𑀲𑀓𑁆𑀬𑀫𑀼𑀦𑀺𑀢𑀺 atana āgāca mahīyite hida Budhe jāte Sakyamuni ti 𑀲𑀺𑀮𑀸𑀯𑀺𑀕𑀥𑀪𑀺𑀘𑀸𑀓𑀸𑀳𑀸𑀧𑀺𑀢 𑀲𑀺𑀮𑀸𑀣𑀪𑁂𑀘 𑀉𑀲𑀧𑀸𑀧𑀺𑀢𑁂 silā vigaḍabhī cā kālāpita silā-thabhe ca usapāpite 𑀳𑀺𑀤𑀪𑀕𑀯𑀁𑀚𑀸𑀢𑀢𑀺 𑀮𑀼𑀁𑀫𑀺𑀦𑀺𑀕𑀸𑀫𑁂 𑀉𑀩𑀮𑀺𑀓𑁂𑀓𑀝𑁂 hida Bhagavaṃ jāte ti Luṃmini-gāme ubalike kaṭe 𑀅𑀞𑀪𑀸𑀕𑀺𑀬𑁂𑀘 aṭha-bhāgiye ca — Adapted from transliteration by E. Hultzsch[182] The Heliodorus pillar is a stone column that was erected around 113 BCE in central India[183] in Vidisha near modern Besnagar, by Heliodorus, an ambassador of the Indo-Greek king Antialcidas in Taxila[184] to the court of the Shunga king Bhagabhadra.

[187] Three immortal precepts (footsteps)... when practiced lead to heaven: self-restraint, charity, consciousness 𑀤𑁂𑀯𑀤𑁂𑀯𑀲 𑀯𑀸(𑀲𑀼𑀤𑁂)𑀯𑀲 𑀕𑀭𑀼𑀟𑀥𑁆𑀯𑀚𑁄 𑀅𑀬𑀁 Devadevasa Vā[sude]vasa Garuḍadhvaje ayaṃ 𑀓𑀭𑀺𑀢𑁄 𑀇(𑀅) 𑀳𑁂𑀮𑀺𑀉𑁄𑀤𑁄𑀭𑁂𑀡 𑀪𑀸𑀕 karito i[a] Heliodoreṇa bhāga- 𑀯𑀢𑁂𑀦 𑀤𑀺𑀬𑀲 𑀧𑀼𑀢𑁆𑀭𑁂𑀡 𑀢𑀔𑁆𑀔𑀲𑀺𑀮𑀸𑀓𑁂𑀦 vatena Diyasa putreṇa Takhkhasilākena 𑀬𑁄𑀦𑀤𑀢𑁂𑀦 𑀅𑀕𑀢𑁂𑀦 𑀫𑀳𑀸𑀭𑀸𑀚𑀲 Yonadatena agatena mahārājasa 𑀅𑀁𑀢𑀮𑀺𑀓𑀺𑀢𑀲 𑀉𑀧𑀁𑀢𑀸 𑀲𑀁𑀓𑀸𑀲𑀁𑀭𑀜𑁄 Aṃtalikitasa upa[ṃ]tā samkāsam-raño 𑀓𑀸𑀲𑀻𑀧𑀼𑀢𑁆𑀭𑀲 𑀪𑀸𑀕𑀪𑀤𑁆𑀭𑀲 𑀢𑁆𑀭𑀸𑀢𑀸𑀭𑀲 Kāsīput[r]asa [Bh]āgabhadrasa trātārasa 𑀯𑀲𑁂𑀦 (𑀘𑀢𑀼)𑀤𑀲𑁂𑀁𑀦 𑀭𑀸𑀚𑁂𑀦 𑀯𑀥𑀫𑀸𑀦𑀲 vasena [catu]daseṃna rājena vadhamānasa

𑀢𑁆𑀭𑀺𑀦𑀺 𑀅𑀫𑀼𑀢𑁋𑀧𑀸𑀤𑀸𑀦𑀺 (𑀇𑀫𑁂) (𑀲𑀼)𑀅𑀦𑀼𑀣𑀺𑀢𑀸𑀦𑀺 Trini amuta𑁋pādāni (i me) (su)anuthitāni 𑀦𑁂𑀬𑀁𑀢𑀺 𑀲𑁆𑀯(𑀕𑀁) 𑀤𑀫 𑀘𑀸𑀕 𑀅𑀧𑁆𑀭𑀫𑀸𑀤 neyamti sva(gam) dama cāga apramāda — Adapted from transliterations by E. J. Rapson,[188] Sukthankar,[189] Richard Salomon,[190] and Shane Wallace.

Obverse: With Greek legend: ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΑΓΑΘΟΚΛΕΟΥΣ .

Reverse: With Brahmi legend: 𑀭𑀸𑀚𑀦𑁂 𑀅𑀕𑀣𑀼𑀓𑁆𑀮𑀬𑁂𑀲 Rājane Agathukleyesa "King Agathocles". Circa 180 BCE. [ 68 ] [ 69 ]

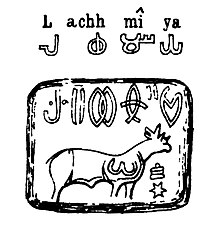

𑀮

La+

𑀺

i; pī=

𑀧

Pa+

𑀻

ii). The word would be of

Old Persian

origin ("Dipi").

The text is Svāmisya Mahakṣatrapasya Śudasasya

"Of the Lord and Great Satrap Śudāsa " [ 139 ]