Industrial Revolution

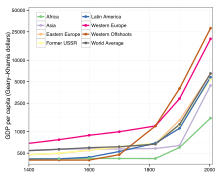

Some economists have said the most important effect of the Industrial Revolution was that the standard of living for the general population in the Western world began to increase consistently for the first time in history, although others have said that it did not begin to improve meaningfully until the late 19th and 20th centuries.

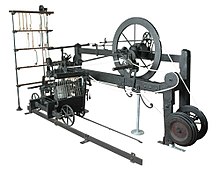

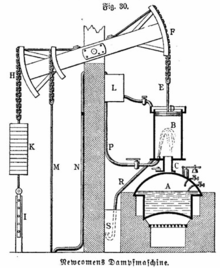

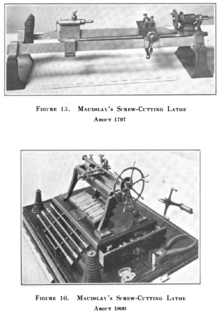

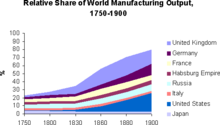

These included new steel-making processes, mass production, assembly lines, electrical grid systems, the large-scale manufacture of machine tools, and the use of increasingly advanced machinery in steam-powered factories.

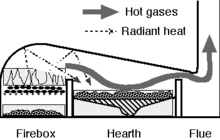

By using preheated combustion air, the amount of fuel to make a unit of pig iron was reduced at first by between one-third using coke or two-thirds using coal;[65] the efficiency gains continued as the technology improved.

[43][26] James Fox of Derby and Matthew Murray of Leeds were manufacturers of machine tools who found success in exporting from England and are also notable for having developed the planer around the same time as Richard Roberts of Manchester.

[44] The change in the social relationship of the factory worker compared to farmers and cottagers was viewed unfavourably by Karl Marx; however, he recognized the increase in productivity made possible by technology.

[106] Some economists, such as Robert Lucas Jr., say that the real effect of the Industrial Revolution was that "for the first time in history, the living standards of the masses of ordinary people have begun to undergo sustained growth ...

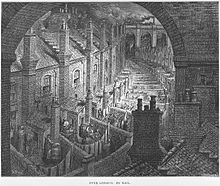

By far the most famous publication was by one of the founders of the socialist movement, The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844 Friedrich Engels describes backstreet sections of Manchester and other mill towns, where people lived in crude shanties and shacks, some not completely enclosed, some with dirt floors.

[124][125] A senior government official told Parliament in 1870: The invention of the paper machine and the application of steam power to the industrial processes of printing supported a massive expansion of newspaper and pamphlet publishing, which contributed to rising literacy and demands for mass political participation.

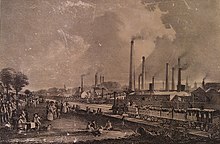

[148] The growth of the modern industry since the late 18th century led to massive urbanisation and the rise of new great cities, first in Europe and then in other regions, as new opportunities brought huge numbers of migrants from rural communities into urban areas.

One British newspaper in 1834 described unions as "the most dangerous institutions that were ever permitted to take root, under shelter of law, in any country..."[174] In 1832, the Reform Act extended the vote in Britain but did not grant universal suffrage.

In 1834 James Frampton, a local landowner, wrote to Prime Minister Lord Melbourne to complain about the union, invoking an obscure law from 1797 prohibiting people from swearing oaths to each other, which the members of the Friendly Society had done.

[182] The first large-scale, modern environmental laws came in the form of Britain's Alkali Acts, passed in 1863, to regulate the deleterious air pollution (gaseous hydrochloric acid) given off by the Leblanc process used to produce soda ash.

The provisions of this law were extended in 1926 with the Smoke Abatement Act to include other emissions, such as soot, ash, and gritty particles, and to empower local authorities to impose their own regulations.

The first industrial exhibition was on the occasion of the coronation of Leopold II as a king of Bohemia, which took place in Clementinum, and therefore celebrated the considerable sophistication of manufacturing methods in the Czech lands during that time period.

Starting in the middle of the 1820s, and especially after Belgium became an independent nation in 1830, numerous works comprising coke blast furnaces as well as puddling and rolling mills were built in the coal mining areas around Liège and Charleroi.

Nevertheless, industrialisation remained quite traditional in the sense that it did not lead to the growth of modern and large urban centres, but to a conurbation of industrial villages and towns developed around a coal mine or a factory.

Unlike the situation in France, the goal was the support of industrialisation, and so heavy lines crisscrossed the Ruhr and other industrial districts and provided good connections to the major ports of Hamburg and Bremen.

Several important institutional changes took place in this period, such as free and mandatory schooling introduced in 1842 (as the first country in the world), the abolition of the national monopoly on trade in handicrafts in 1846, and a stock company law in 1848.

He had learned of the new textile technologies as a boy apprentice in Derbyshire, England, and defied laws against the emigration of skilled workers by leaving for New York in 1789, hoping to make money with his knowledge.

Realising that the War of 1812 had ruined his import business but that demand for domestic finished cloth was emerging in America, on his return to the United States, he set up the Boston Manufacturing Company.

[221] New Industrialism calls for building enough housing to satisfy demand in order to reduce the profit in land speculation, to invest in infrastructure, and to develop advanced technology to manufacture green energy for the world.

In addition to metal ores, Britain had the highest quality coal reserves known at the time, as well as abundant water power, highly productive agriculture, and numerous seaports and navigable waterways.

He also cites the monastic emphasis on order and time-keeping, as well as the fact that medieval cities had at their centre a church with bell ringing at regular intervals as being necessary precursors to a greater synchronisation necessary for later, more physical, manifestations such as the steam engine.

Conversely, Chinese society was founded on men like Confucius, Mencius, Han Feizi (Legalism), Lao Tzu (Taoism), and Buddha (Buddhism), resulting in very different worldviews.

[256] Instead, the greater liberalisation of trade from a large merchant base may have allowed Britain to produce and use emerging scientific and technological developments more effectively than countries with stronger monarchies, particularly China and Russia.

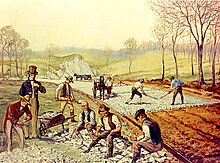

Peasant resistance to industrialisation was largely eliminated by the Enclosure movement, and the landed upper classes developed commercial interests that made them pioneers in removing obstacles to the growth of capitalism.

[263][264] A 2022 study in the Journal of Political Economy by Morgan Kelly, Joel Mokyr, and Cormac O Grada found that industrialization happened in areas with low wages and high mechanical skills, whereas literacy, banks and proximity to coal had little explanatory power.

During the whole of the Industrial Revolution and for the century before, all European countries and America engaged in study-touring; some nations, like Sweden and France, even trained civil servants or technicians to undertake it as a matter of state policy.

The Unitarians, in particular, were very involved in education, by running Dissenting Academies, where, in contrast to the universities of Oxford and Cambridge and schools such as Eton and Harrow, much attention was given to mathematics and the sciences – areas of scholarship vital to the development of manufacturing technologies.

The movement stressed the importance of "nature" in art and language, in contrast to "monstrous" machines and factories; the "Dark satanic mills" of Blake's poem "And did those feet in ancient time".