Infinite monkey theorem

Variants of the theorem include multiple and even infinitely many typists, and the target text varies between an entire library and a single sentence.

Jorge Luis Borges traced the history of this idea from Aristotle's On Generation and Corruption and Cicero's De Natura Deorum (On the Nature of the Gods), through Blaise Pascal and Jonathan Swift, up to modern statements with their iconic simians and typewriters.

[2] In the early 20th century, Borel and Arthur Eddington used the theorem to illustrate the timescales implicit in the foundations of statistical mechanics.

Therefore, at least one of infinitely many monkeys will (with probability equal to one) produce a text using the same number of keystrokes as a perfectly accurate human typist copying it from the original.

This can be stated more generally and compactly in terms of strings, which are sequences of characters chosen from some finite alphabet: Both follow easily from the second Borel–Cantelli lemma.

In fact, there is less than a one in a trillion chance of success that such a universe made of monkeys could type any particular document a mere 79 characters long.

Thus, the probability of the monkey typing an endlessly long string, such as all of the digits of pi in order, on a 90-key keyboard is (1/90)∞ which equals (1/∞) which is essentially 0.

In one of the forms in which probabilists now know this theorem, with its "dactylographic" [i.e., typewriting] monkeys (French: singes dactylographes; the French word singe covers both the monkeys and the apes), appeared in Émile Borel's 1913 article "Mécanique Statique et Irréversibilité" (Static mechanics and irreversibility),[1] and in his book "Le Hasard" in 1914.

Borel said that if a million monkeys typed ten hours a day, it was extremely unlikely that their output would exactly equal all the books of the richest libraries of the world; and yet, in comparison, it was even more unlikely that the laws of statistical mechanics would ever be violated, even briefly.

The physicist Arthur Eddington drew on Borel's image further in The Nature of the Physical World (1928), writing: If I let my fingers wander idly over the keys of a typewriter it might happen that my screed made an intelligible sentence.

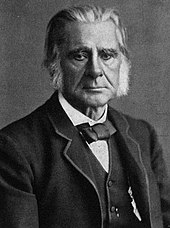

In a 1939 essay entitled "The Total Library", Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges traced the infinite-monkey concept back to Aristotle's Metaphysics.

[11]Borges follows the history of this argument through Blaise Pascal and Jonathan Swift,[12] then observes that in his own time, the vocabulary had changed.

Borges then imagines the contents of the Total Library which this enterprise would produce if carried to its fullest extreme: Everything would be in its blind volumes.

Everything: the detailed history of the future, Aeschylus' The Egyptians, the exact number of times that the waters of the Ganges have reflected the flight of a falcon, the secret and true name of Rome, the encyclopedia Novalis would have constructed, my dreams and half-dreams at dawn on August 14, 1934, the proof of Pierre Fermat's theorem, the unwritten chapters of Edwin Drood, those same chapters translated into the language spoken by the Garamantes, the paradoxes Berkeley invented concerning Time but didn't publish, Urizen's books of iron, the premature epiphanies of Stephen Dedalus, which would be meaningless before a cycle of a thousand years, the Gnostic Gospel of Basilides, the song the sirens sang, the complete catalog of the Library, the proof of the inaccuracy of that catalog.

They left a computer keyboard in the enclosure of six Celebes crested macaques in Paignton Zoo in Devon, England from May 1 to June 22, with a radio link to broadcast the results on a website.

[21] A more common argument is represented by Reverend John F. MacArthur, who claimed that the genetic mutations necessary to produce a tapeworm from an amoeba are as unlikely as a monkey typing Hamlet's soliloquy, and hence the odds against the evolution of all life are impossible to overcome.

[22] Evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins employs the typing monkey concept in his book The Blind Watchmaker to demonstrate the ability of natural selection to produce biological complexity out of random mutations.

As Dawkins acknowledges, however, the weasel program is an imperfect analogy for evolution, as "offspring" phrases were selected "according to the criterion of resemblance to a distant ideal target."

[23] In terms of the typing monkey analogy, this means that Romeo and Juliet could be produced relatively quickly if placed under the constraints of a nonrandom, Darwinian-type selection because the fitness function will tend to preserve in place any letters that happen to match the target text, improving each successive generation of typing monkeys.

[24]James W. Valentine, while admitting that the classic monkey's task is impossible, finds that there is a worthwhile analogy between written English and the metazoan genome in this other sense: both have "combinatorial, hierarchical structures" that greatly constrain the immense number of combinations at the alphabet level.

But the interest of the suggestion lies in the revelation of the mental state of a person who can identify the 'works' of Shakespeare with the series of letters printed on the pages of a book ...[27]Nelson Goodman took the contrary position, illustrating his point along with Catherine Elgin by the example of Borges' "Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote", What Menard wrote is simply another inscription of the text.

[30] In 1979, William R. Bennett Jr., a profesor of physics at Yale University, brought fresh attention to the theorem by applying a series of computer programs.

Dr. Bennett simulated varying conditions under which an imaginary monkey, given a keyboard consisting of twenty-eight characters, and typing ten keys per second, might attempt to reproduce the sentence, "To be or not to be, that is the question."

Although his experiments agreed with the overall conclusion that even such a short string of words would require many times the current age of the universe to reproduce, he noted that by modifying the statistical probability of certain letters to match the ordinary patterns of various languages and of Shakespeare in particular, seemingly random strings of words could be made to appear.

But even with several refinements, the English sentence closest to the target phrase remained gibberish: "TO DEA NOW NAT TO BE WILL AND THEM BE DOES DOESORNS CAI AWROUTROULD.

"[31] The theorem concerns a thought experiment which cannot be fully carried out in practice, since it is predicted to require prohibitive amounts of time and resources.

[33] Questions about the statistics describing how often an ideal monkey is expected to type certain strings translate into practical tests for random-number generators; these range from the simple to the "quite sophisticated".

[j] This is helped by the innate humor stemming from the image of literal monkeys rattling away on a set of typewriters, and is a popular visual gag.

The enduring, widespread popularity of the theorem was noted in the introduction to a 2001 paper, "Monkeys, Typewriters and Networks: The Internet in the Light of the Theory of Accidental Excellence".

[38] In 2003, the previously mentioned Arts Council−funded experiment involving real monkeys and a computer keyboard received widespread press coverage.