Infrarealism

[1] Rather than a defined style, the movement was characterised by the pursuit of a free and personal poetry, representative of its members' attitude towards life on the fringes of conventional society, in a similar manner to the Beat Generation of the 1950s.

The intellectual Emmanuel Berl attributes it to one of the founders of Surrealism, the writer and political activist Philippe Soupault (1897–1990), who was also one of the driving forces behind Dadaism.

[10] In 1968, at a time when the future Infrarealist poets were still children and adolescents, the so-called Dirty War began to take shape in Mexico during the presidency of Gustavo Díaz Ordaz (Institutional Revolutionary Party, 1964–1970).

Amongst its principal consequences was the Tlatelolco Massacre in the Ciudad Universitaria of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), where an estimated 300 to 400 students and civilians were murdered by military and police.

He was the ex-Secretariat of the Interior in the government of Díaz Ordaz, who was considered by the majority of the Mexican population as one of the principal culprits of the Dirty War.

[11] Infrarealism emerged at the end of Luis Echeverría's government in the midst of this effervescence of literary workshops in Mexico City, which were allowing many young people to begin to develop as poets and novelists.

The first of these worlds referred to artists who were granted scholarships or received benefits in some way from the Institutional Revolutionary Party's government – among them, for example, José Luis Cuevas and Fernando Benítz.

For the Infrarealists, this group also included writers and intellectuals of world renown, such as Octavio Paz or Carlos Monsiváis, who, despite not needing Echeverría's direct support, cultivated a dedicated readership, ran important literary magazines, and also benefited from tax revenues.

In October of the same year, in Plural number 61, Mario Santiago Papasquiaro published a review and translation of poems by the beat poet and novelist Richard Brautigan.

Based in Mexico, he was a regular of Café La Habana, where Bolaño and Papasquiaro held their Infrarealist meetings, and sympathised with the youthful energy of the infras.

Eleven Young Latin American Poets), an anthology of poems featuring Luis Suardíaz, Hernán Lavín Cerda, Jorge Pimentel, Orlando Guillén, Beltrán Morales, Fernando Nieto Cadena, Julián Gómez, Enrique Verástegui, Mario Santiago Papasquairo, Bruno Montané and Bolaño himself.

Rubén Medina went to study literature in the United States; Harrington returned to Chile to study film; Gelles Lebrija went to live in Tijuana; Piel Divina to Paris; the Méndez brothers returned to their hometown Morelia, where they worked in journalism, and for a time as bakers; José Vicente Anaya dedicated himself to travelling around Mexico for four years; Lorena de la Rocha chose classical music composition and theatre; and the Larrosa sisters stayed in Mexico City, with Vera devoting herself to dance and theatre,[3] and Mara to painting.

[3] Between April 1980 and February 1981, poems from this new group of Infraealists appeared in three issues of Le Prosa magazine, edited by Orlando Guillén.

[10] Between November 1984 and July 1990, the Infrarealists published a poetry pamphlet titled Calandria de tolvaneras, which also included poems from older members like Roberto Bolaño and Bruno Montané.

[10] A decade after his death, Mario Raúl Guzman and Rebeca López, Papasquario's widow, published Jeta de santo.

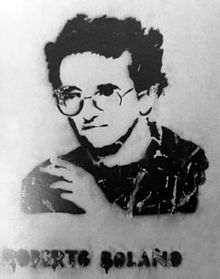

[25] Bolaño undoubtedly achieved the greatest international prestige out of the older Infrarealists, establishing himself as a novelist in Barcelona and publishing numerous works for Editorial Anagrama.