Initial public offering of Facebook

The main reason that the company decided to go public is because it crossed the threshold of 500 shareholders, according to Reuters financial blogger Felix Salmon.

In 2007 Microsoft beat out Google to purchase a 1.6% stake for $240 million, giving Facebook a notional value of $15 billion at the time.

[10] The preliminary prospectus announced that the company had 845 million active monthly users and that its website featured 2.7 billion daily likes and comments.

[12] To ensure that early investors would retain control of the company, Facebook in 2009 instituted a dual-class stock structure.

[24] On May 16, two days before the IPO, Facebook announced that it would sell 25% more shares than originally planned due to high demand.

Some investors expressed keen interest in Facebook because they felt they had missed out on the massive gains Google saw in the wake of its IPO.

[26] A number of commentators argued retrospectively that Facebook had been heavily overvalued because of an illiquid private market on SecondMarket, where trades of stock were minimal and thus pricing unstable.

Facebook's aggregate valuation went up from January 2011 to April 2012, before plummeting after the IPO in May - but this was in a largely illiquid market, with less than 120 trades each quarter during 2010 and 2011.

"Valuations in the private market are going to make it 'difficult to go public'", according to Mary Meeker, an American venture capitalist and former Wall Street securities analyst.

On May 14, before the offering price was announced, Sterne Agee analyst Arvind Bhatia pegged the company at $46 in an interview with The Street.

Citing the price-to-earnings ratio of 108 for 2011, critics stated that the company would have to undergo "almost ridiculous financial growth [for the valuation] to make sense.

Writers at TechCrunch expressed similar skepticism, stating, "That's a big multiple to live up to, and [Facebook] will likely need to add bold new revenue streams to justify the mammoth valuation".

[21] Rolfe Winkler of the Wall Street Journal suggested that, given insider worries, the public should avoid snapping up the stock.

[21] Striking an optimistic tone, The New York Times predicted that the offering would overcome questions about Facebook's difficulties in attracting advertisers to transform the company into a "must-own stock".

[12] Brian Wieser of Pivotal Research Group argued that, "Although Facebook is very promising, it's an unproven ad model.

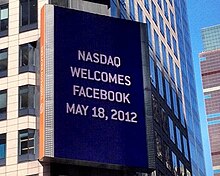

[31] Zuckerberg rang a bell from Hacker Square on Facebook campus in Menlo Park, California, to announce the offering, as is customary for CEOs on the day their companies go public.

[38] Despite technical problems and a relatively low closing value, the stock set a new record for trading volume of an IPO (460 million shares).

[39] The IPO also ended up raising $16 billion, making it the third largest in U.S. history (just ahead of AT&T Wireless and behind only General Motors and Visa Inc.).

[32] Additionally, the rival New York Stock Exchange lampooned the move as a "harmful precedent" and an unnecessary subsidy in the wake of Nasdaq's missteps.

[12] CBS News said "the Facebook brand takes a pretty big hit for this," mostly because of the public interest that had surrounded the offering.

"[12] While the Wall Street Journal called for a broad perspective on the issue, they agreed that valuations and funding for future startup IPOs could take a hit.

[44] Analyst Trip Chowdhry suggested an even broader conclusion with regards to IPOs, arguing "that hype doesn't sell anymore, short of fundamentals.

[44] While expected to provide significant benefits to Nasdaq, the IPO resulted in a strained relationship between Facebook and the exchange.

have filed lawsuits, alleging that an underwriter for Morgan Stanley selectively revealed adjusted earnings estimates to preferred clients.

[57] It is believed that adjustments to earnings estimates were communicated to the underwriters by a Facebook financial officer, who in turn used the information to cash out on their positions while leaving the general public with overpriced shares.

[61] On 22 May, regulators from Wall Street's Financial Industry Regulatory Authority announced that they had begun to investigate whether banks underwriting Facebook had improperly shared information only with select clients, rather than the general public.

[62] The allegations sparked "fury" among some investors and led to the immediate filing of several lawsuits, one of them a class action suit claiming more than $2.5 billion in losses due to the IPO.

[63] Before the creation of secondary market exchanges like SecondMarket and SharesPost, shares of private companies had very little liquidity; however, this is no longer the case.

Underwriting equity offerings became an important part of Morgan's business after the financial crisis, generating $1.2 billion in fees since 2010.

But by signing off on an offering price that was too high, or attempting to sell too many shares to the market, Morgan compounded problems, senior editor for CNN Money Stephen Gandel writes.