Inland Customs Line

The line was gradually expanded as more territory was brought under British control until it covered more than 2,500 miles (4,000 km), often running alongside rivers and other natural barriers.

The line was initially made of dead, thorny material such as the Indian plum but eventually evolved into a living hedge that grew up to 12 feet (3.7 m) high and was compared to the Great Wall of China.

The line and hedge were abandoned in 1879 when the British seized control of the Sambhar Salt Lake in Rajasthan and applied tax at the point of manufacture.

In 1803 a series of customs houses and barriers were constructed across major roads and rivers in Bengal to collect the tax on traded salt as well as duties on tobacco and other imports.

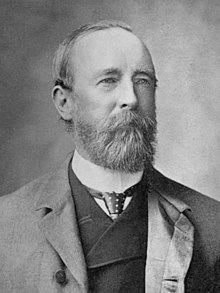

[10][11] Smith exempted items such as tobacco and iron from taxation to concentrate on salt and was responsible for expanding and improving the line, increasing its budget to 790,000 rupees per year and the staff to 6,600 men.

The department staffed each post with an Indian Jemadar (approximately equivalent to a British Warrant Officer) and ten men, backed up by patrols operating 2–3 miles behind the line.

[16] In 1869 the government in Calcutta ordered the connection of sections of the line into a continuous customs barrier stretching 2,504 miles (4,030 km) from the Himalayas to Orissa, near the Bay of Bengal.

[18] The north section from Tarbela to Multan was lightly guarded with posts spread further apart as the wide Indus River was judged to provide a sufficient barrier to smuggling.

The more heavily guarded section was around 1,429 miles (2,300 km) long and began at Multan, running along the rivers Sutlej and Yamuna before terminating south of Burhanpur.

[25] This hedge was at risk of attack by white ants, rats, fire, storms, locusts, parasitic creepers, natural decay and strong winds which could destroy furlongs at a time and necessitated constant maintenance.

[27] In 1869 Hume, in preparation for a rapid expansion of the live hedge, began trials of various indigenous thorny shrubs to see which would be suited to different soil and rainfall conditions.

[33] The living hedge was terminated at Burhanpur in the south, beyond which it could not grow, and at Layyah in the north where it met the River Indus, whose strong current was judged sufficient to deter smugglers.

[34] Historian Henry Francis Pelham compared the use of the Indus in this way to that of the River Main, in modern Germany, for the Roman Limes Germanicus fortifications.

[26][35] The line was altered slightly in 1875–6 to run alongside the newly built Agra Canal, which was judged a sufficient obstacle to allow the distance between guard posts to be increased to 1.5 miles (2.4 km).

[40][45] The officers undertook at least one customs excursion per day on average, weighing and applying tax to almost 200 pounds (91 kg) of goods, in addition to personally patrolling around 9 miles (14 km) of the line.

[46] This was partly due to the use of the line for the collection of taxes on sugar (which made up 10 per cent of the revenues) as well as salt, meaning that traffic had to be stopped and searched in both directions.

[47] The viceroys were also displeased with the corruption and bribery which was present in the Inland Customs system, and the way the line came to serve as a symbol of unjust taxes (parts were set on fire during the Indian Rebellion of 1857).

[14][19] However, the government could not afford to lose the revenue generated by the line and hence, before they could abolish it, needed to take control of all salt production in India, so that tax could be applied at the point of manufacture.

[46] The Viceroy from 1869 to 1872, Lord Mayo, took the first steps towards abolition of the line, instructing British officials to negotiate agreements with the rulers of princely states to take control of salt production.

[48] The process was speeded up by Mayo's successor, Lord Northbrook, and by the loss of revenue caused by the Great Famine of 1876–78 that reduced the land tax and killed 6.5 million people.

[50] This reduced difference in tax between neighbouring territories made smuggling uneconomical and allowed for the abandonment of the Inland Customs Line on 1 April 1879.

[18] This has been echoed by modern writers such as journalist Madeleine Bunting, who wrote in The Guardian in February 2001 that the line was "one of the most grotesque and least well known achievements of the British in India".

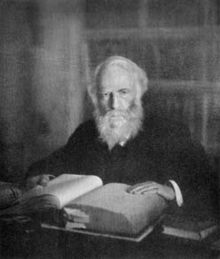

[65] The massive scale of the undertaking has also been commented upon, with both Hume, the customs commissioner, and M. E. Grant Duff, who was Under-Secretary of State for India from 1868 to 1874, comparing the hedge to the Great Wall of China.

[1][30] The abolition of the line and equalisation of tax has generally been viewed as a good move, with one writer of 1901 stating that it "relieved the people and the trade along a broad belt of country, 2,000 miles long, from much harassment".

[54] Sir Richard Temple, governor of the Bengal and Bombay Presidencies, wrote in 1882 that "the inland customs line for levying the salt-duties has been at length swept away" and that care must be taken to ensure that the "evils of the obsolete transit-duties" did not return.

Early on, when patrols were patchy, large scale smuggling was common, with armed gangs breaking through the line with herds of salt-laden camels or cattle.

This followed his finding, in 1995, of a passing mention of the hedge in Major-General Sir William Henry Sleeman's work Rambles and Recollections of an Indian Official.

[81] Artist Sheila Ghelani and Sue Palmer produced live art performances of a piece called "Common Salt", about the hedge.

The delegates saw it as proof enough that the world could forget anything – including the cost of nuclear warfare or the grave dangers posed by improperly disposing of radioactive waste – all of which could have severe consequences if ever erased from public memory.