Earth's inner core

In 1952, Francis Birch published a detailed analysis of the available data and concluded that the inner core was probably crystalline iron.

[16] Adam Dziewonski and James Freeman Gilbert established that measurements of normal modes of vibration of Earth caused by large earthquakes were consistent with a liquid outer core.

As it happens with other material properties, the density drops suddenly at that surface: The liquid just above the inner core is believed to be significantly less dense, at about 12.1 kg/L.

[26][27] In 2010, Bruce Buffett determined that the average magnetic field in the liquid outer core is about 2.5 milliteslas (25 gauss), which is about 40 times the maximum strength at the surface.

He started from the known fact that the Moon and Sun cause tides in the liquid outer core, just as they do on the oceans on the surface.

He observed that motion of the liquid through the local magnetic field creates electric currents, that dissipate energy as heat according to Ohm's law.

This dissipation, in turn, damps the tidal motions and explains previously detected anomalies in Earth's nutation.

However, based on the relative prevalence of various chemical elements in the Solar System, the theory of planetary formation, and constraints imposed or implied by the chemistry of the rest of the Earth's volume, the inner core is believed to consist primarily of an iron–nickel alloy.

[5] Laboratory experiments and analysis of seismic wave velocities seem to indicate that the inner core consists specifically of ε-iron, a crystalline form of the metal with the hexagonal close-packed (HCP) structure.

[19][31] Many scientists had initially expected that the inner core would be found to be homogeneous, because that same process should have proceeded uniformly during its entire formation.

[35] Some authors have claimed that P wave speed is faster in directions that are oblique or perpendicular to the N−S axis, at least in some regions of the inner core.

[37] Laboratory data and theoretical computations indicate that the propagation of pressure waves in the HCP crystals of ε-iron are strongly anisotropic, too, with one "fast" axis and two equally "slow" ones.

[19] One phenomenon that could cause such partial alignment is slow flow ("creep") inside the inner core, from the equator towards the poles or vice versa.

[29] On the other hand, M. Bergman in 1997 proposed that the anisotropy was due to an observed tendency of iron crystals to grow faster when their crystallographic axes are aligned with the direction of the cooling heat flow.

[36] However, the conclusion has been disputed by claims that there need not be sharp discontinuities in the inner core, only a gradual change of properties with depth.

They suggest that atoms in the IIC atoms are [packed] slightly differently than its outer layer, causing seismic waves to pass through the IIC at different speeds than through the surrounding core (P-wave speeds ~4% slower at ~50° from the Earth’s rotation axis).

With some assumptions on the evolution of the Earth, they conclude that the fluid motions in the outer core would have entered resonance with the tidal forces at several times in the past (3.0, 1.8, and 0.3 billion years ago).

During those epochs, which lasted 200–300 million years each, the extra heat generated by stronger fluid motions might have stopped the growth of the inner core.

[4] Two main approaches have been used to infer the age of the inner core: thermodynamic modeling of the cooling of the Earth, and analysis of paleomagnetic evidence.

One of the ways to estimate the age of the inner core is by modeling the cooling of the Earth, constrained by a minimum value for the heat flux at the core–mantle boundary (CMB).

[59] In 2012, theoretical computations by M. Pozzo and others indicated that the electrical conductivity of iron and other hypothetical core materials, at the high pressures and temperatures expected there, were two or three times higher than assumed in previous research.

[62][64] However, in 2016 Konôpková and others directly measured the thermal conductivity of solid iron at inner core conditions, and obtained a much lower value, 18–44 W/m·K.

With those values, they obtained an upper bound of 4.2 billion years for the age of the inner core, compatible with the paleomagnetic evidence.

They interpreted that change as evidence that the dynamo effect was more deeply seated in the core during that epoch, whereas in the later time currents closer to the core-mantle boundary grew in importance.

[60] In 2015, Biggin and others published the analysis of an extensive and carefully selected set of Precambrian samples and observed a prominent increase in the Earth's magnetic field strength and variance around 1.0–1.5 billion years ago.

[63] In 2016, P. Driscoll published a numerical evolving dynamo model that made a detailed prediction of the paleomagnetic field evolution over 0.0–2.0 Ga.

The evolving dynamo model was driven by time-variable boundary conditions produced by the thermal history solution in Driscoll and Bercovici (2014).

[73] An analysis of rock samples from the Ediacaran epoch (formed about 565 million years ago), published by Bono and others in 2019, revealed unusually low intensity and two distinct directions for the geomagnetic field during that time that provides support for the predictions by Driscoll (2016).

Considering other evidence of high frequency of magnetic field reversals around that time, they speculate that those anomalies could be due to the onset of formation of the inner core, which would then be 0.5 billion years old.

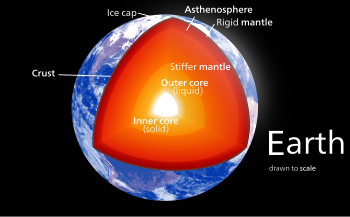

-

upper mantle

-

lower mantle

-

inner core

- Mohorovičić discontinuity

- core–mantle boundary

- outer core–inner core boundary