Integral field spectrograph

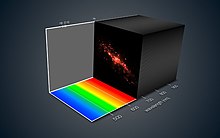

For spectroscopic studies, the optimum would then be to get a spectrum for each spatial pixel in the instrument field of view, getting full information on each target.

Since then, other snapshot hyperspectral imaging techniques, based for example on tomographic reconstruction[1] or compressed sensing using a coded aperture,[2] have been developed.

[3] One major advantage of the snapshot approach for ground-based telescopic observations is that it automatically provides homogenous data sets despite the unavoidable variability of Earth’s atmospheric transmission, spectral emission and image blurring during exposures.

After a slow start from the late 1980s on, Integral field spectroscopy has become a mainstream astrophysical tool in the optical to mid-infrared regions, addressing a whole gamut of astronomical sources, essentially any smallish individual object from Solar System asteroids to vastly distant galaxies.

The lenslet array output is a regular grid of as many small telescope mirror images, which serves as the input for a multi-slit spectrograph[4] that delivers the data cubes.

Pros are 100% on-sky spatial filling when using a square or hexagonal lenslet shape, high throughput, accurate photometry and an easy to build IFU.

A significant con is the suboptimal use of precious detector pixels (~ 50% loss at least) in order to avoid contamination between adjacent spectra.

In 2009 the BIGRE [10] lenslet array was proposed to correctly approach the case of spatial and spectral samplings above the Nyquist rate over diffraction limited scenes, as required to high-contrast imaging spectroscopy.

This optical concept widely improves the use of detector pixels thanks to the resulting spectrograph line spread function, minimizing inter-spectra crosstalk effects.

It is typically made of a few thousands fibers each about 0.1 mm diameter, with the square or circular input field reformatted into a narrow rectangular (long-slit-like) output.

Cons are the sizable light loss in the fibers (~ 25%), their relatively poor photometric accuracy and their inability to work in a cryogenic environment.

The first mirror-based slicer near-infrared IFS, the Spectrometer for Infrared Faint Field Imaging[19] (SPIFFI)[20] got its first science result[21] in 2003.

Pros are high throughput, 100% on-sky spatial filling, optimal use of detector pixels and the capability to work at cryogenic temperatures.

The Fibre Large Array Multi Element Spectrograph (FLAMES),[29] the first instrument featuring this capability, had first light in this mode at the VLT in 2002.