International Campaign to Save the Monuments of Nubia

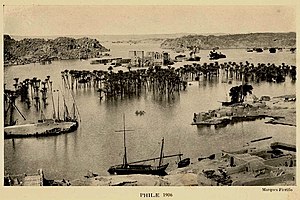

This was done in order to make way for the building of the Aswan Dam, at the Nile's first cataract (shallow rapids), a project launched following the 1952 Egyptian Revolution.

[2] The construction of the Aswan Dam was a key objective of the new regime the Free Officers movement of 1952 in order to better control flooding, provide increased water storage for irrigation and generate hydroelectricity,[3] all of which were seen as pivotal for the industrialization of Egypt.

By 1959, Tharwat Okasha, the Egyptian Minister of Culture sought to work alongside UNESCO to safeguard and preserve Nubian monuments.

The level of fieldwork for the project had not been previous undertaken on equivalent scale or length of time, leaving many to praise the campaign as a feat of the field of archeology.

[8] Christiane Desroches Noblecourt, who remained in charge of the CEDAE (Centre d'Étude et de Documentation sur l'Ancienne Égypte, in English the Documentation and Study Centre for the History of the Art and Civilization of Ancient Egypt) in Cairo, held a leading role within the archeological survey aspect of the campaign.

[8] A honorary committee was first founded by King Gustav VI Adolf of Sweden to create international support for the campaign, with various world political leaders and UNESCO members as participants.

[6] An official International Action Committee was established after under the UNESCO Director General in order to secure funding, service, and equipment from participating member states.

[10] The construction of Lake Nasser, as well as the excavations required in the Nubia campaign, involved the relocation of many Nubians native to the region.

The forced relocation stripped many native Nubians of their ancestral homelands, with the compensation of unsuitable homes for living and agriculture.

Only one archaeological site in Lower Nubia, Qasr Ibrim, remains in its original location and above water; previously a cliff-top settlement, it was transformed into an island.

Next the monuments were cleaned and measured, by using photogrammetry, a method that enables the exact reconstruction of the original size of the building blocks that were used by the ancients.

Then every building was dismantled into about 40,000 units from 2 to 25 tons, and then transported to the nearby Island of Agilkia,[23] situated on higher ground some 500 metres (1,600 ft) away.

[24] In addition to participating directly in the high profile salvage operations of Abu Simbel and Philae, the Egyptian Antiquities Organization carried out the rescue of many smaller temples and monuments alone using their own financial and technical means.

The temples of Wadi es-Sebua and Beit el Wali and the rock tomb of Pennut at Aniba were moved in 1964 with the support of a US grant, whilst the subsequent re-erection was carried out with Egyptian resources.

"[30] Given the impending flooding of a wide area, Egypt and Sudan encouraged archaeological teams from across the world to carry out work as broadly as possible.

Some of this work took place at the CEDAE (Centre d'Étude et de Documentation sur l'Ancienne Égypte, in English the Documentation and Study Centre for the History of the Art and Civilization of Ancient Egypt), founded in Cairo in 1955 to coordinate the academic efforts:[32] The table below summarizes the contributions towards the project by the global coalition of nations.