International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants

The initiative for the foundation of UPOV came from European breeding companies, who 1956 called for a conference to define basic principles for plant variety protection.

A reason for this development might be the TRIPS-Agreement that obliged WTO members to introduce plant variety protection in national law.

[5] Later, many countries have been obliged to join UPOV through specific clauses in bilateral trade agreements, in particular with the EU, USA, Japan and EFTA.

[6] The TRIPS-Agreement doesn't require adherence to UPOV but gives the possibility to define a sui generis system for plant variety protection.

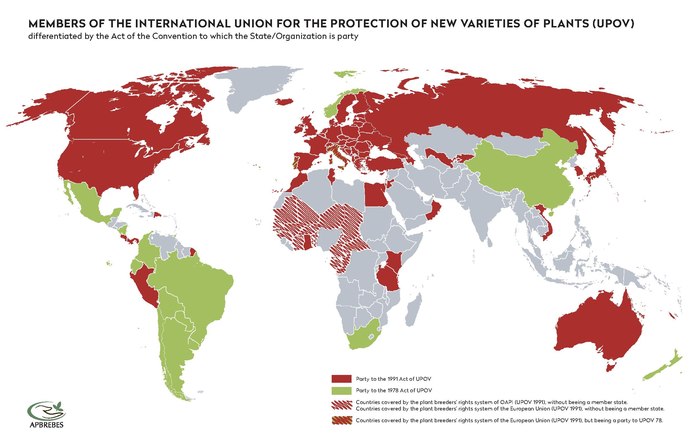

[8] As of December 3, 2021 two intergovernmental organisations and 76 countries and were members of UPOV:[4] African Intellectual Property Organisation, Albania, Argentina, Australia, Austria, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Belgium, Bolivia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Brazil, Bulgaria, Canada, Chile, China, Colombia, Costa Rica, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Egypt, Estonia, European Union,[9] Finland, France, Georgia,[10] Germany, Ghana,[11] Guatemala, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Jordan, Kenya, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, Lithuania, Mexico, Moldova, Montenegro, Morocco, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Nicaragua, North Macedonia, Norway, Oman, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Poland, Portugal, Republic of Korea, Romania, Russian Federation, Serbia, Singapore, Slovakia, Slovenia, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Tanzania, Trinidad and Tobago, Tunisia, Turkey, Ukraine, the United Kingdom, the United States of America (with a reservation),[12] Uruguay, Uzbekistan, and Viet Nam.

UPOV's secretariat analyises the regulation of plant variety protection in national law and writes a recommendation to the council whether or not the applicant shall be granted membership.

[14] In the past several countries have been refused memberships because their national plant variety protection laws granted exceptions for subsistence farmers to reuse and exchange seeds.

[18] The convention defines both how the organization must be governed and run, and the basic concepts of plant variety protection that must be included in the domestic laws of the members of the union.

[22] The breeder must authorize any actions taken in propagating the new variety, including selling and marketing, importing and exporting, keeping stock of, and reproducing.

[31] Furthermore, as implementation of UPOV is based on predefined standards, there is little room for member states to fulfill their obligation to take into account possible effects on the human right situation in their countries and to allow for participation of farmers.

[32] In many developing countries, small scale farmers have not been informed prior to adopting and implementation of new plant variety protection laws and had no possibility participate in these decisions.

The supreme court sacked the UPOV 91-based law because it judged it to be in contradiction with a range of human rights as well as with the obligation of the State of Honduras to protect the environment.

[39] A report from 2005 commissioned by the World Bank looked at the impact of intellectual property rights regimes on the plant breeding industry in 5 developing countries.

India, the country with the most dynamic seed sector analysed in the report, is not a member of UPOV and has no strict plant variety protection regime.

[43] It found that in the 17 member countries only 117 plant varieties have been newly protected during this period, half of them had already lapsed because of nonpayment of fees.

[46] The study found that the productivity of 3 major staple crops increased during this period: Yield gains were 18% for rice, 30% for corn and 43% for sweet potato.

[47] A Study published by an Asian NGO finds that implementation of UPOV 91 in Vietnam did not lead to an increase of investment in breeding or in gains of productivity.

They predominantly rely on seeds that are produced by farmers themselves,[49] often also including varieties originally bred by public and private breeders.

Breeders rely on farmers’ varieties and wild relatives as a source for interesting traits, such as resistance against pathogens and pests.

As the UN's Secretary General stated in a report from 2015, restrictions on seed management systems linked to UPOV 91 can lead to a loss of biodiversity and in turn harm the livelihoods of small-scale farmers as well as weaken the genetic base on which we all depend for our future supply of food.

UPOV 91-based PVP law also does not include a requirement for applicants to disclose the origin of their material and prove that the plant genetic resources used in the breeding process were legally acquired.

[32] In its guidelines, UPOV even explicitly forbids its members to request a declaration of lawful acquirement or prior informed consent (as required by the Convention on Biological Diversity) as precondition for granting PVP.

Several social movements and civil society organisations such as South Center, GRAIN, AFSA, SEARICE, Third World Network, and La Via Campesina[57] have criticised UPOV Secretariatpointed.

"[35] Currently, however, the EFTA states, including Switzerland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Iceland are negotiating free trade agreements with Thailand and Malaysia.