International Phonetic Alphabet

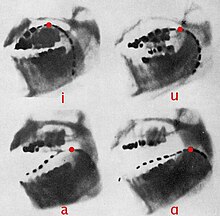

[2][3] The IPA is designed to represent those qualities of speech that are part of lexical (and, to a limited extent, prosodic) sounds in oral language: phones, intonation and the separation of syllables.

[1] To represent additional qualities of speech – such as tooth gnashing, lisping, and sounds made with a cleft palate – an extended set of symbols may be used.

After relatively frequent revisions and expansions from the 1890s to the 1940s, the IPA remained nearly static until the Kiel Convention in 1989, which substantially revamped the alphabet.

Among the symbols of the IPA, 107 letters represent consonants and vowels, 31 diacritics are used to modify these, and 17 additional signs indicate suprasegmental qualities such as length, tone, stress, and intonation.

[6] The Association created the IPA so that the sound values of most letters would correspond to "international usage" (approximately Classical Latin).

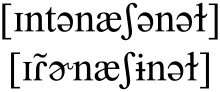

A narrower transcription may focus on individual or dialectical details: [ˈɫɪɾɫ] in General American, [ˈlɪʔo] in Cockney, or [ˈɫɪːɫ] in Southern US English.

Phonemic transcriptions, which express the conceptual counterparts of spoken sounds, are usually enclosed in slashes (/ /) and tend to use simpler letters with few diacritics.

The choice of IPA letters may reflect theoretical claims of how speakers conceptualize sounds as phonemes or they may be merely a convenience for typesetting.

[45] Authors who employ such nonstandard use are encouraged to include a chart or other explanation of their choices, which is good practice in general, as linguists differ in their understanding of the exact meaning of IPA symbols and common conventions change over time.

[52] Opera librettos are authoritatively transcribed in IPA, such as Nico Castel's volumes[53] and Timothy Cheek's book Singing in Czech.

In official publications by the IPA, two columns are omitted to save space, with the letters listed among "other symbols" even though theoretically they belong in the main chart.

Those superscript letters listed below are specifically provided for by the IPA Handbook; other uses can be illustrated with ⟨tˢ⟩ ([t] with fricative release), ⟨ᵗs⟩ ([s] with affricate onset), ⟨ⁿd⟩ (prenasalized [d]), ⟨bʱ⟩ ([b] with breathy voice), ⟨mˀ⟩ (glottalized [m]), ⟨sᶴ⟩ ([s] with a flavor of [ʃ], i.e. a voiceless alveolar retracted sibilant), ⟨oᶷ⟩ ([o] with diphthongization), ⟨ɯᵝ⟩ (compressed [ɯ]).

A series of alveolar plosives ranging from open-glottis to closed-glottis phonation is: Additional diacritics are provided by the Extensions to the IPA for speech pathology.

These include prosody, pitch, length, stress, intensity, tone and gemination of the sounds of a language, as well as the rhythm and intonation of speech.

[note 31] The Chao tone letters, on the other hand, may be combined in any pattern, and are therefore used for more complex contours and finer distinctions than the diacritics allow, such as mid-rising [e˨˦], extra-high falling [e˥˦], etc.

Unicode supports default or high-pitch ⟨ˉ ˊ ˋ ˆ ˇ ˜ ˙⟩ and low-pitch ⟨ˍ ˏ ˎ ꞈ ˬ ˷⟩.

[note 33] The system allows the transcription of 112 peaking and dipping pitch contours, including tones that are level for part of their length.

To some extent this may be an effect of analysis, but it is common to match up single IPA letters to the phonemes of a language, without overly worrying about phonetic precision.

[94] This has the advantage of merging the upper-pharyngeal fricatives [ħ, ʕ] together with the epiglottal plosive [ʡ] and trills [ʜ ʢ] into a single pharyngeal column in the consonant chart.

However, in precise notation there is a difference between a fricative release in [tᶴ] and the affricate [t͜ʃ], between a velar onset in [ᵏp] and doubly articulated [k͜p].

Letters for specific combinations of primary and secondary articulation have also been mostly retired, with the idea that such features should be indicated with tie bars or diacritics: ⟨ƍ⟩ for [zʷ] is one.

In addition, the rare voiceless implosives, ⟨ƥ ƭ ƈ ƙ ʠ ⟩, were dropped soon after their introduction and are now usually written ⟨ɓ̥ ɗ̥ ʄ̊ ɠ̊ ʛ̥ ⟩.

They are, however, often used in conjunction with the IPA in two cases: Wildcards are commonly used in phonology to summarize syllable or word shapes, or to show the evolution of classes of sounds.

[note 44] Typical examples of archiphonemic use of capital letters are ⟨I⟩ for the Turkish harmonic vowel set {i y ɯ u};[note 45] ⟨D⟩ for the conflated flapped middle consonant of American English writer and rider; ⟨N⟩ for the homorganic syllable-coda nasal of languages such as Spanish and Japanese (essentially equivalent to the wild-card usage of the letter); and ⟨R⟩ in cases where a phonemic distinction between trill /r/ and flap /ɾ/ is conflated, as in Spanish enrejar /eNreˈxaR/ (the n is homorganic and the first r is a trill, but the second r is variable).

This summary is to some extent valid internationally, but linguistic material written in other languages may have different associations with capital letters used as wildcards.

The remaining pulmonic consonants – the uvular laterals ([ʟ̠ 𝼄̠ ʟ̠˔]) and the palatal trill – while not strictly impossible, are very difficult to pronounce and are unlikely to occur even as allophones in the world's languages.

[note 50] Letters which are not directly derived from these alphabets, such as ⟨ʕ⟩, may have a variety of names, sometimes based on the appearance of the symbol or on the sound that it represents.

[122] Web browsers generally do not need any configuration to display IPA characters, provided that a typeface capable of doing so is available to the operating system.

Brill has complete IPA and extIPA coverage of characters added to Unicode by 2020, with good diacritic and tone-letter support.

The usage of mapping systems in on-line text has to some extent been adopted in the context input methods, allowing convenient keying of IPA characters that would be otherwise unavailable on standard keyboard layouts.