International Workingmen's Association in America

These sections were divided geographically and by the language spoken by their members, frequently new immigrants to America, including those who spoke German, French, Czech, as well as Irish and "American" English-language groups.

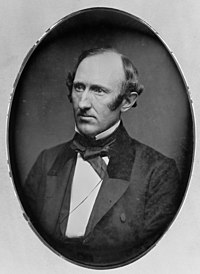

[1] Orsini managed to win the support of a number of a handful of émigré socialists in New York City, in addition to gaining a sympathetic hearing from several prominent political figures, including newspaper editor Horace Greeley, abolitionist orator Wendell Phillips, and radical Republican Senator Charles Sumner.

[5] The Social Party adopted a platform which incorporated elements both of the program of the International as well as that of the fledgling National Labor Union (NLU) established less than two years earlier by William H.

[5] Following the 1868 electoral failure, the Social Party of New York dissolved and its leading German-speaking members established a new organization called the Allgemeiner Deutscher Arbeiterverein (General German Workers' Association).

Vilified by the conservative press, iconoclasts and radicals of all stripes in America rallied to the revolutionary city government of Paris, which was closely linked with the International Workingmen's Association in the public mind, if not in actual practice.

[13] Although the Parisian barricades were overrun by defenders of the old regime in May amidst a bloody reaction that claimed as many as 20,000 lives, the French events nevertheless occupied the thinking of a generation in much in the same way that the Russian Revolution of 1917 would have a polarizing and far reaching impact nearly half a century later.

[14] The National Anti-Slavery Standard carried regular dispatches from Paris and kept its readers informed of the legal and political retribution levied against Commune leaders in the aftermath of the failed uprising.

[17] The largest Spiritualist weekly, Banner of Light, attempted to explain for its readers the motivations and actions of the Communards, declaring they were "weary of the servitude that practically accompanies the wages condition, when all exercise of political power is denied it.

[23] Covering a broad range of subjects running the gamut from abolitionism to feminism to labor reform to Spiritualism, in 1871 the paper dedicated significant coverage to the Paris Commune and the entity commonly imagined to be behind it, the IWA.

[21] Also active in Section 12 was Stephen Pearl Andrews, an abolitionist who had previously established a failed utopian socialist community on Long Island called "Modern Times.

"by reason of faith in their respective blueprints of what America ought to be, counted first, on the spread of enlightenment and the democratic process to cleanse government of corruption, and then, on meliorative laws to direct the nation toward their primal model.

[26] It pushed forward with its own program of eclectic social reform in 1872, bringing a protest from the doctrinaire international socialists of Section 1, who demanded the suspension from the organization for their ideological heresy of their erstwhile comrades.

[27] In March 1872 the General Council issued its ruling, suspending Section 12 from the organization and ordering the two rival executive bodies to unite into a single provisional committee pending formal resolution at the next national convention.

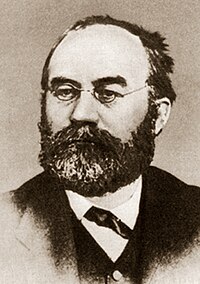

[30] Marx saw a socialist future as the inevitable result of a process of economic growth and development, with the revolutionary transformation making it possible conducted by an educated and disciplined working class led by a political party.

[30] In the view of Bakunin, the new world would emerge via the revolt of the poor and oppressed masses, workers and peasant farmers alike, suffering under the heel of an exploitative semi-feudal economic and political structure.

[31] He sought the forcible destruction of state power and its replacement with what historian Juilius Braunthal has characterized as a "stateless federation of communes free from all outside coercion and authority.

"[31] Marx, on the other hand, saw a long process of education and organization as a necessary precursor for a revolutionary overthrow of the ruling class, followed by a "withering away" of the coercive state in the new non-exploitative world.

[31] In short, Bakunin and Marx agreed upon little, rejected the fundamental ideas of the other, and saw themselves as antagonistic rivals locked in an irreconcilable conflict for control of the fledgling IWA organization.