Virtual community

The widespread use of the Internet and virtual communities by millions of diverse users for socializing is a phenomenon that raises new issues for researchers and developers.

The vast number and diversity of individuals participating in virtual communities worldwide makes it a challenge to test usability across platforms to ensure the best overall user experience.

Some well-established measures applied to the usability framework for online communities are speed of learning, productivity, user satisfaction, how much people remember using the software, and how many errors they make.

[12] People communicate their social identities or culture code through the work they do, the way they talk, the clothes they wear, their eating habits, domestic environments and possessions, and use of leisure time.

The information provided during a usability test can determine demographic factors and help define the semiotic social code.

[18] Individuals who suffer from rare or severe illnesses are unable to meet physically because of distance or because it could be a risk to their health to leave a secure environment.

[20] Over the years, things have changed, as new forms of civic engagement and citizenship have emerged from the rise of social networking sites.

Online content-sharing sites have made it easy for youth as well as others to not only express themselves and their ideas through digital media, but also connect with large networked communities.

Within these spaces, young people are pushing the boundaries of traditional forms of engagement such as voting and joining political organizations and creating their own ways to discuss, connect, and act in their communities.

The two main effects that can be seen according to Benkler are a "thickening of preexisting relations with friends, family and neighbours" and the beginnings of the "emergence of greater scope for limited-purpose, loose relationships".

[24] Sherry Turkle, professor of Social Studies of Science and Technology at MIT, believes the internet is a place where actions of discrimination are less likely to occur.

For these reasons, Turkle argues users existing in online spaces are less compelled to judge or compare themselves to their peers, allowing people in virtual settings an opportunity to gain a greater capacity for acknowledging diversity.

Identity tourism, in the context of cyberspace, is a term used to the describe the phenomenon of users donning and doffing other-race and other-gender personae.

People use everything from clothes, voice, body language, gestures, and power to identify others, which plays a role with how they will speak or interact with them.

Smith and Kollock believes that online interactions breaks away of all of the face-to-face gestures and signs that people tend to show in front of one another.

[27] The gaming community is extremely vast and accessible to a wide variety of people, However, there are negative effects on the relationships "gamers" have with the medium when expressing identity of gender.

[28] According to Lisa Nakamura, representation in video games has become a problem, as the minority of players from different backgrounds who are not just the stereotyped white teen male gamer are not represented.

The lack of status that is presented with an online identity also might encourage people, because, if one chooses to keep it private, there is no associated label of gender, age, ethnicity or lifestyle.

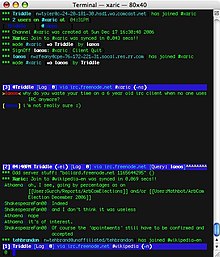

[32] Shortly after the rise of interest in message boards and forums, people started to want a way of communicating with their "communities" in real time.

Benefits from virtual world technology such as photo realistic avatars and positional sound create an atmosphere for participants that provides a less fatiguing sense of presence.

The exchange and consumption of information requires a degree of "digital literacy", such that users are able to "archive, annotate, appropriate, transform and recirculate media content" (Jenkins).

Howard Rheingold's Virtual Community could be compared with Mark Granovetter's ground-breaking "strength of weak ties" article published twenty years earlier in the American Journal of Sociology.

His comment on the first page even illustrates the social networks in the virtual society: "My seven year old daughter knows that her father congregates with a family of invisible friends who seem to gather in his computer.

Indeed, in his revised version of Virtual Community, Rheingold goes so far to say that had he read Barry Wellman's work earlier, he would have called his book "online social networks".

Lipnack and Stamps (1997)[38] and Mowshowitz (1997) point out how virtual communities can work across space, time and organizational boundaries; Lipnack and Stamps (1997)[38] mention a common purpose; and Lee, Eom, Jung and Kim (2004) introduce "desocialization" which means that there is less frequent interaction with humans in traditional settings, e.g. an increase in virtual socialization.

Recently, Mitch Parsell (2008) has suggested that virtual communities, particularly those that leverage Web 2.0 resources, can be pernicious by leading to attitude polarization, increased prejudices and enabling sick individuals to deliberately indulge in their diseases.

This interaction allows people to engage in many activities from their home, such as: shopping, paying bills, and searching for specific information.

Consumers generally feel very comfortable making transactions online provided that the seller has a good reputation throughout the community.

Virtual communities also provide the advantage of disintermediation in commercial transactions, which eliminates vendors and connects buyers directly to suppliers.

[42] In theory, online identities can be kept anonymous which enables people to use the virtual community for fantasy role playing as in the case of Second Life's use of avatars.