Interval (music)

Some of the very smallest ones are called commas, and describe small discrepancies, observed in some tuning systems, between enharmonically equivalent notes such as C♯ and D♭.

For this reason, intervals are often measured in cents, a unit derived from the logarithm of the frequency ratio.

These names identify not only the difference in semitones between the upper and lower notes but also how the interval is spelled.

The importance of spelling stems from the historical practice of differentiating the frequency ratios of enharmonic intervals such as G–G♯ and G–A♭.

[4] The size of an interval (also known as its width or height) can be represented using two alternative and equivalently valid methods, each appropriate to a different context: frequency ratios or cents.

When a musical instrument is tuned using a just intonation tuning system, the size of the main intervals can be expressed by small-integer ratios, such as 1:1 (unison), 2:1 (octave), 5:3 (major sixth), 3:2 (perfect fifth), 4:3 (perfect fourth), 5:4 (major third), 6:5 (minor third).

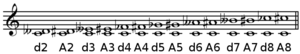

The table shows the most widely used conventional names for the intervals between the notes of a chromatic scale.

There is a one-to-one correspondence between staff positions and diatonic-scale degrees (the notes of diatonic scale).

Notice that interval numbers represent an inclusive count of encompassed staff positions or note names, not the difference between the endpoints.

For that reason, the interval E–E, a perfect unison, is also called a prime (meaning "1"), even though there is no difference between the endpoints.

The name of any interval is further qualified using the terms perfect (P), major (M), minor (m), augmented (A), and diminished (d).

Since the inversion does not change the pitch class of the two notes, it hardly affects their level of consonance (matching of their harmonics).

Consonance and dissonance are relative terms that refer to the stability, or state of repose, of particular musical effects.

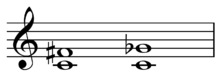

For example, the four intervals listed in the table below are all enharmonically equivalent, because the notes F♯ and G♭ indicate the same pitch, and the same is true for A♯ and B♭.

There are also a number of minute intervals not found in the chromatic scale or labeled with a diatonic function, which have names of their own.

Intervals larger than a major seventeenth seldom come up, most often being referred to by their compound names, for example "two octaves plus a fifth"[22] rather than "a 19th".

They are typically defined as the combination of intervals starting from a common note called the root of the chord.

The interval qualities or numbers in boldface font can be deduced from chord name or symbol by applying rule 1.

To facilitate comparison, just intervals as provided by 5-limit tuning (see symmetric scale n.1) are shown in bold font, and the values in cents are rounded to integers.

The above-mentioned symmetric scale 1, defined in the 5-limit tuning system, is not the only method to obtain just intonation.

In particular, the asymmetric version of the 5-limit tuning scale provides a juster value for the minor seventh (9:5, rather than 16:9).

In the diatonic system, every interval has one or more enharmonic equivalents, such as augmented second for minor third.

The root of a perfect fourth, then, is its top note because it is an octave of the fundamental in the hypothetical harmonic series.

A superscript may be added to distinguish between transpositions, using 0–11 to indicate the lowest pitch class in the cycle.

5-limit tuning defines four kinds of comma, three of which meet the definition of diminished second, and hence are listed in the table below.

For instance, 22 kinds of intervals, called shrutis, are canonically defined in Indian classical music.

Up to the end of the 18th century, Latin was used as an official language throughout Europe for scientific and music textbooks.

[26][27][28] Namely, a semitonus, semiditonus, semidiatessaron, semidiapente, semihexachordum, semiheptachordum, or semidiapason, is shorter by one semitone than the corresponding whole interval.

Combined, these yield the progression diminished, subminor, minor, neutral, major, supermajor, augmented for seconds, thirds, sixths, and sevenths.

Notice that staff positions, when used to determine the conventional interval number (second, third, fourth, etc.