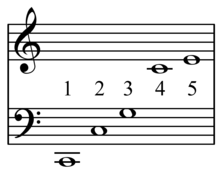

Major third

For example, the interval from C to E is a major third, as the note E lies four semitones above C, and there are three staff positions from C to E. The intervals from the tonic (keynote) in an upward direction to the second, to the third, to the sixth, and to the seventh scale degrees of a major scale are called "major".

The major chord also takes its name from the presence of this interval built on the chord's root (provided that the interval of a perfect fifth from the root is also present).

A major third is slightly different in different musical tunings: In just intonation it corresponds to a pitch ratio of 5:4, or 5 / 4 (playⓘ) (fifth harmonic in relation to the fourth) or 386.31 cents; in 12 tone equal temperament, a major third is equal to four semitones, a ratio of 21/3:1 (about 1.2599) or 400 cents, 13.69 cents wider than the 5:4 ratio.

The older concept of a "ditone" (two 9:8 major seconds) made a dissonant, wide major third with the ratio 81:64 (about 1.2656) or 408 cents (playⓘ), about 22 cents sharp from the harmonic ratio of 5:4 .

For example, A♭ to C, C to E, and E to G♯ (in 12 TET, the differently written notes G♯ and A♭ both represent the same pitch, but not in most other tuning systems).

In the common practice period, thirds were considered interesting and dynamic consonances along with their inverses the sixths, but in medieval times they were considered dissonances unusable in a stable final sonority.

In equal temperament, a diminished fourth is enharmonically equivalent to a major third (that is, it spans the same number of semitones).

For example, B–D♯ is a major third; but if the same pitches are spelled as the notes B and E♭, then the interval they represent is instead a diminished fourth.

The difference in pitch is erased in 12 tone equal temperament, where the distinction is only nominal, but the difference between a major third and a diminished fourth is significant in almost all other musical tuning systems.