Introduction to the mathematics of general relativity

As a result, relativity requires the use of concepts such as vectors, tensors, pseudotensors and curvilinear coordinates.

For an introduction based on the example of particles following circular orbits about a large mass, nonrelativistic and relativistic treatments are given in, respectively, Newtonian motivations for general relativity and Theoretical motivation for general relativity.

A scalar, that is, a simple number without a direction, would be shown on a graph as a point, a zero-dimensional object.

A second-order tensor has two magnitudes and two directions, and would appear on a graph as two lines similar to the hands of a clock.

For example, the velocity 5 meters per second upward could be represented by the vector (0, 5) (in 2 dimensions with the positive y axis as 'up').

Tensors also have extensive applications in physics: In general relativity, four-dimensional vectors, or four-vectors, are required.

In physics, as well as mathematics, a vector is often identified with a tuple, or list of numbers, which depend on a coordinate system or reference frame.

Coordinate transformation is important because relativity states that there is not one reference point (or perspective) in the universe that is more favored than another.

As an example event, assume that Earth is a motionless object, and consider the signing of the Declaration of Independence.

To a modern observer on Mount Rainier looking east, the event is ahead, to the right, below, and in the past.

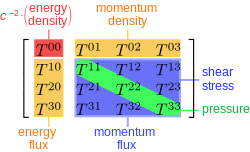

In general relativity, one cannot describe the energy and momentum of the gravitational field by an energy–momentum tensor.

Instead, one introduces objects that behave as tensors only with respect to restricted coordinate transformations.

While maps frequently portray north, south, east and west as a simple square grid, that is not in fact the case.

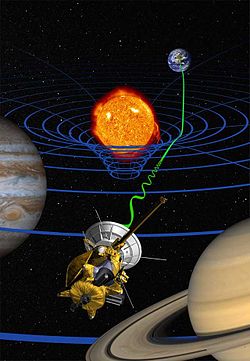

In general relativity, energy and mass have curvature effects on the four dimensions of the universe (= spacetime).

The Christoffel symbols find frequent use in Einstein's theory of general relativity, where spacetime is represented by a curved 4-dimensional Lorentz manifold with a Levi-Civita connection.

The Einstein field equations – which determine the geometry of spacetime in the presence of matter – contain the Ricci tensor.

Once the geometry is determined, the paths of particles and light beams are calculated by solving the geodesic equations in which the Christoffel symbols explicitly appear.

Importantly, the world line of a particle free from all external, non-gravitational force, is a particular type of geodesic.

In general relativity, gravity can be regarded as not a force but a consequence of a curved spacetime geometry where the source of curvature is the stress–energy tensor (representing matter, for instance).

The solution is a useful approximation for describing slowly rotating astronomical objects such as many stars and planets, including Earth and the Sun.

According to Birkhoff's theorem, the Schwarzschild metric is the most general spherically symmetric, vacuum solution of the Einstein field equations.