Introduction to gauge theory

The culmination of these efforts is the Standard Model, a quantum field theory that accurately predicts all of the fundamental interactions except gravity.

[5] Later Hermann Weyl, inspired by success in Einstein's general relativity, conjectured (incorrectly, as it turned out) in 1919 that invariance under the change of scale or "gauge" (a term inspired by the various track gauges of railroads) might also be a local symmetry of electromagnetism.

After the development of quantum mechanics, Weyl, Vladimir Fock and Fritz London modified their gauge choice by replacing the scale factor with a change of wave phase, and applying it successfully to electromagnetism.

[8] Gauge symmetry was generalized mathematically in 1954 by Chen Ning Yang and Robert Mills in an attempt to describe the strong nuclear forces.

This gauge theory, known as the Standard Model, accurately describes experimental predictions regarding three of the four fundamental forces of nature.

Thus one could choose to define all voltage differences relative to some other standard, rather than the Earth, resulting in the addition of a constant offset.

In other words, the laws of physics governing electricity and magnetism (that is, Maxwell equations) are invariant under gauge transformation.

The relevant point here is that the fields remain the same under the gauge transformation, and therefore Maxwell's equations are still satisfied.

, which implies that no experiment should be able to measure the absolute potential, without reference to some external standard such as an electrical ground.

Some global symmetries under changes of coordinate predate both general relativity and the concept of a gauge.

Again, if one observer had examined a hydrogen atom today and the other—100 years ago (or any other time in the past or in the future), the two experiments would again produce completely identical results.

Because light from hydrogen atoms in distant galaxies may reach the earth after having traveled across space for billions of years, in effect one can do such observations covering periods of time almost all the way back to the Big Bang, and they show that the laws of physics have always been the same.

Until the advent of quantum mechanics, the only well known example of gauge symmetry was in electromagnetism, and the general significance of the concept was not fully understood.

For example, it was not clear whether it was the fields E and B or the potentials V and A that were the fundamental quantities; if the former, then the gauge transformations could be considered as nothing more than a mathematical trick.

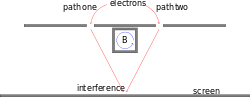

The electron has the highest probability of being detected at locations where the parts of the wave passing through the two slits are in phase with one another, resulting in constructive interference.

The results of the experiment will be different, because phase relationships between the two parts of the electron wave have changed, and therefore the locations of constructive and destructive interference will be shifted to one side or the other.

In reality, the results are different, because turning on the solenoid changed the vector potential A in the region that the electrons do pass through.

Now that it has been established that it is the potentials V and A that are fundamental, and not the fields E and B, we can see that the gauge transformations, which change V and A, have real physical significance, rather than being merely mathematical artifacts.

Note that in these experiments, the only quantity that affects the result is the difference in phase between the two parts of the electron wave.

Suppose we imagine the two parts of the electron wave as tiny clocks, each with a single hand that sweeps around in a circle, keeping track of its own phase.

In summary, gauge symmetry attains its full importance in the context of quantum mechanics.

[18] Gauge symmetry is required in order to make quantum electrodynamics a renormalizable theory, i.e., one in which the calculated predictions of all physically measurable quantities are finite.

The description of the electrons in the subsection above as little clocks is in effect a statement of the mathematical rules according to which the phases of electrons are to be added and subtracted: they are to be treated as ordinary numbers, except that in the case where the result of the calculation falls outside the range of 0≤θ<360°, we force it to "wrap around" into the allowed range, which covers a circle.

Other examples of abelian groups are the integers under addition, 0, and negation, and the nonzero fractions under product, 1, and reciprocal.

In 1954, Chen Ning Yang and Robert Mills proposed to generalize these ideas to noncommutative groups.

There is also a corresponding local gauge symmetry, which describes the fact that from one moment to the next, Alice and Betty could swap roles while nobody was looking, and nobody would be able to tell.

The fact that the symmetry is local means that we cannot even count on these proportions to remain fixed as the particles propagate through space.

Motion can only be described in terms of waves, and the momentum p of an individual particle is related to its wavelength λ by p = h/λ.

Although the function θ(x) describes a wave, the laws of quantum mechanics require that it also have particle properties.

This is the case for the gauge bosons that carry the weak interaction: the force responsible for nuclear decay.